It was a cool winter morning in 1878 when a young British officer by the name of Edward Law Durand (5 June 1845 - 1 July 1920) swept ashore onto the island of Muharraq in Bahrain. Sent by the British Political Residency to conduct an archaeological survey (funded by the British Museum) of the island, his report of the burial mounds was the first archaeological study conducted in the country and in the Gulf since the time of Alexander (or Rome even).

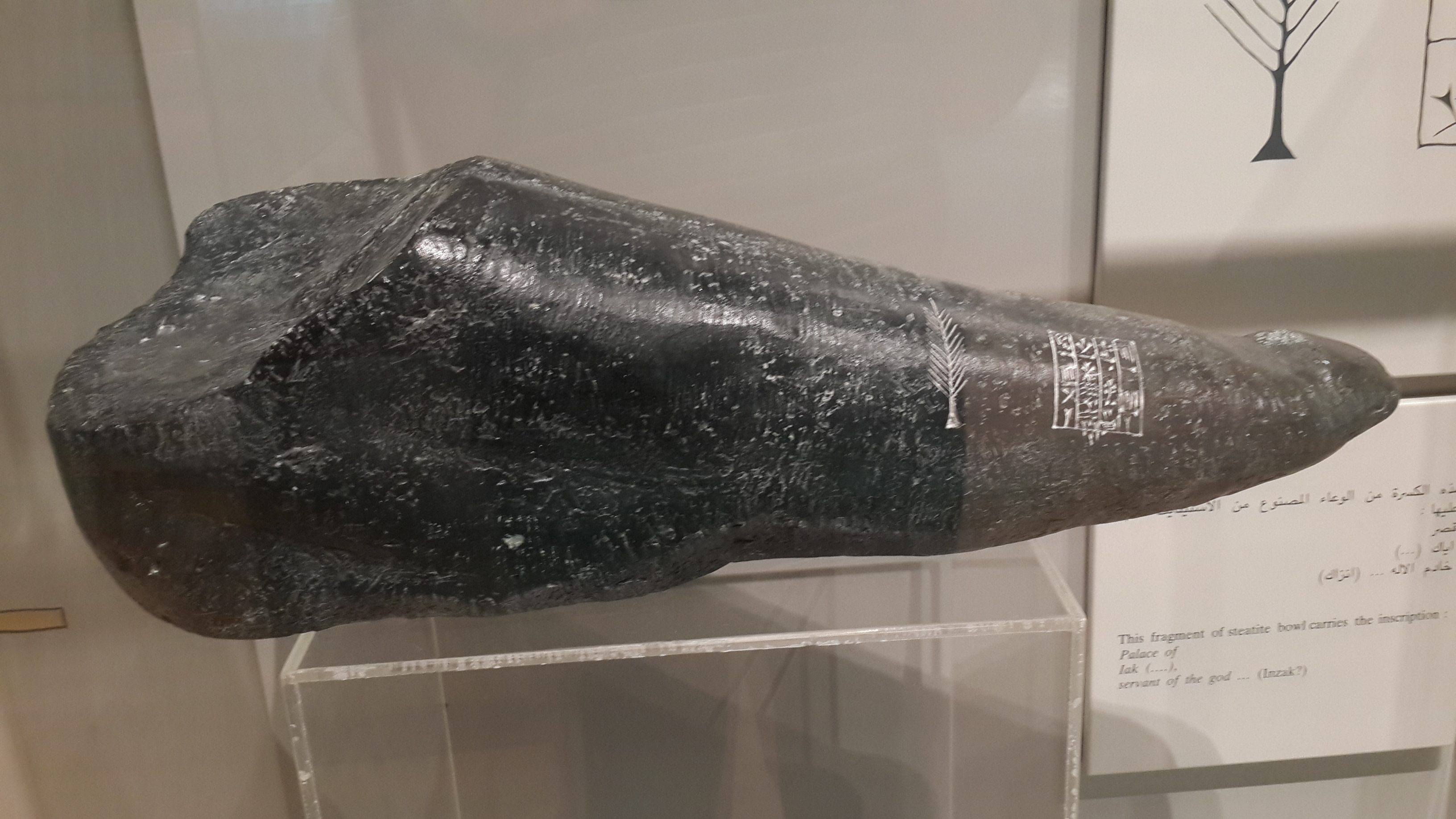

It was on this occasion that he thus became the first European writer to comment on the Bronze Age burial-mounds there, and had the fortune to discover a cuneiform inscription (named the Durand Stone) which he brought back to his family home in Scotland but which was later moved to London where it is believed to have been destroyed during the Blitz.

Durand's Stone is important as it contained Old Babylonian inscriptions. Only when translated by Sir Henry Rawlinson (the forefront scholar in Mesopotamian affairs) did its content become known; it spoke of a devout servant of Dilmun divinity. This quintessentially cemented the Dilmun-Bahrain hypothesis, wherein it is believed Bahrain is the location of the fabled land of Dilmun.

First, a biography of the man;

Durand's report on the island (completed in 1879) was forwarded by Ross to A.C. Lyall, then Secretary of the Government of India's Foreign Department, and was later published in 1880 in the 'Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society' (New Series) vol. XII (Part II), pp. 189-227, where it was entitled "Extracts from Report on the Islands and Antiquities of Bahrain" (reproduced with an introduction by Michael Rice in 'Dilmun Discovered: the early years of archaeology in Bahrain', London/New York: Longman 1984, pp. 9-36).

Durand, being a fervent watercolour enthusiast, was said to have painted hundreds of watercolours of Bahrain. Unfortunately, they have been lost to history (although his watercolours from his time in India and Afghanistan exist)

Fortunately, the lovely people at the Qatar Digital Library digitised and uploaded Durand's report, so you may browse it at your leisure. I recommend you go through it, it contains rather vivid descriptions of an island long gone. I'll conclude with Durand's eloquent description of dawn after a particularly sleepless night.

References:

|

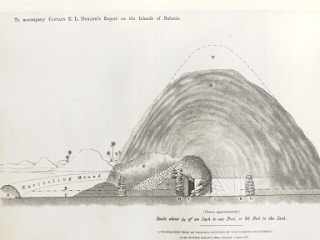

| Sketch of a mound from Durand's report (via Qatar Digital Library) |

Durand's Stone is important as it contained Old Babylonian inscriptions. Only when translated by Sir Henry Rawlinson (the forefront scholar in Mesopotamian affairs) did its content become known; it spoke of a devout servant of Dilmun divinity. This quintessentially cemented the Dilmun-Bahrain hypothesis, wherein it is believed Bahrain is the location of the fabled land of Dilmun.

First, a biography of the man;

One of three sons of Sir Henry Marion Durand (1812-1871), who had served with distinction in the First Afghan War and the Indian Mutiny. Educated at Bath, Repton and Guildford; entered the 96th Regiment of Foot in 1865 but transferred to the Indian Political Service in 1868 and in 1870 was selected as ADC and Private Secretary to the Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab. From 1871-77 he filled various posts in Rajputana and Central India, before briefly serving as Acting Political Agent in Manipur in 1877. In the following year (1878) he was appointed Acting Assistant Resident in Bushire [during which he was sent to Bahrain]. In 1881 Durand was placed in charge of the former Amir of Kabul and from 1884-86 he was Assistant Commissioner for the Afghan Boundary Commission. In 1888 he was appointed Resident in Nepal , where he served from 1889 until his retirement in 1893. He was author of 'Cyrus the Great King' (verse; London 1906), and 'Rifle, Rod, and Spear in the East' (London 1911). He died in London.- The British Museum

Durand's report on the island (completed in 1879) was forwarded by Ross to A.C. Lyall, then Secretary of the Government of India's Foreign Department, and was later published in 1880 in the 'Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society' (New Series) vol. XII (Part II), pp. 189-227, where it was entitled "Extracts from Report on the Islands and Antiquities of Bahrain" (reproduced with an introduction by Michael Rice in 'Dilmun Discovered: the early years of archaeology in Bahrain', London/New York: Longman 1984, pp. 9-36).

Durand, being a fervent watercolour enthusiast, was said to have painted hundreds of watercolours of Bahrain. Unfortunately, they have been lost to history (although his watercolours from his time in India and Afghanistan exist)

Fortunately, the lovely people at the Qatar Digital Library digitised and uploaded Durand's report, so you may browse it at your leisure. I recommend you go through it, it contains rather vivid descriptions of an island long gone. I'll conclude with Durand's eloquent description of dawn after a particularly sleepless night.

References:

- 'NOTES ON THE ISLANDS OF BAHRAIN AND ANTIQUITIES BY CAPTAIN E. L. DURAND, 1 ASSISTANT RESIDENT, PERSIAN GULF.' [31r] (24/32), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/L/PS/18/B95, in Qatar Digital Library [accessed 16 August 2015]

- The Archaeology of the Arabian Gulf by Michael Rice