The history of architecture in Bahrain, like many other aspects, is a neglected one. At present, the Kingdom is home to an estimated 1.4 million people. In the most recent census in 2010, the number of dwellings was estimated at 140,000 buildings (an all-time high). With the trends of globalization in full swing in Bahrain over the past century (starting with its education sector a century ago), Bahraini architecture began to be overtaken by concrete-based Western designs as the country aimed to build itself as a financial hub in the 20th Century.

Newly-reclaimed lands in the Diplomatic Area and the high-rise commercial buildings that have dotted the Manama skyline since the 1980s have been testament to this. But with the rush towards the future, it is very easy to forget about the past and how we got here. To put it dramatically - a nation that forgets its past can have no future (as said by the genocidal Winston Churchill)

So today, I present an article on the architecture of an affluent Bahraini house. Unfortunately, this will not discuss barastis (houses used by the poorer population mostly in Manama) and I wholeheartedly apologise for this.

The Traditional Bahraini House:

|

| The Isa Bin Ali Al-Khalifa House, in Muharraq (2008). |

A traditional affluent Bahraini house was made up of a series of pavilions around a courtyard. Traditionally, houses had two courtyards (though sometimes only one); one would host the reception of men and the other would be for private living use. The more economical option adopted by modest households was a singular courtyard. However, such options depended on multiple factors such as family size, business needs etc.

The house's rooms were organised in terms of seasonal migration, with the important pavilions for living and hosting receptions having a counterpart on the roof to capture summer breezes and redirect it into the pavilion. The lower rooms of the house would have thick walls, allowing them to be utilised during the cool winter months.

To combat the intense heat during the summer months, a framework of coral rubble piers with spaces filled with large panels of coral rocks (with a thickness rarely more than 4cm) were erected. In the higher levels, the panels were arranged in a two-lead construction, with trapped air in between to reduce thermal conductivity when the sun shines on the outside walls. The light-weight and porous coral is lined with a coat of lime and gypsum (again keeping to a minimal thickness of 1/8 cm), reducing the capacity of the walls to store daytime heat into the evenings when it might have been re-radiated at a time of high humidity to cause discomfort.

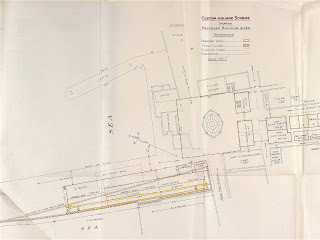

|

| A diagram showing the anatomy of the spatial composition, the unique architectural language and the visual features of Muharraq houses, the case of Sh. Salman House (Source: Yarwood, 1988) |

Hundreds of buildings with this feature were built in Bahrain but virtually none currently function, with most not being repaired or serviced in several decades. A disadvantage of the coral used is that its core is made from clay, as a mortar, and dissolves easily because of its soapy consistency. As a result, this causes cracks to develop in the walls during rainy weather, compromising the structure's stability and requiring yearly maintenance.

The most famous example of such a house would be the

Shaikh Isa bin Ali al-Khalifa house, built in 1830 and recently restored as a national monument. The house is built around four courtyards and includes beautifully incised stucco panels in the upper rooms.

Designs of such continuous cross-ventilation through rooms in hot & humid climates originated back to the time of ancient Assyria in the 6th century BC although even earlier models have been found in structures dating to 3000 BC. The concept of pier-and-opening construction was favoured in ancient Egypt and the Greek islands of ancient Ionia.

Bonus Topic - A Brief History of Coral Building

|

| Detail of coral carving on the premises of Male' Friday Mosque © Dominic Sansoni (Fair Use) |

Coral as a building material was used primarily along coastal settlements throughout the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. Believed to have originated from the Red Sea coasts, the earliest example of its use was at the site of Al-Rih in Sudan where a Greek cornice made of coral was found re-used in an Islamic tomb. It then spread to the East African coast and was primarily used as building material for monuments.

In the Persian Gulf, there is another tradition of coral stone construction although the antiquity of this tradition is being questioned as suitable coral has only grown in the area within the past 1,000 years. At present, coral stone building have been seen along the coastline of Gujarat in India, the Maldives and Sri Lanka - believed to have been associated with Islamic traders.

Two types of coral were used for construction; fossil coral from the coast shore (more suitable for load-bearing walls) and reef coral cut live from the sea bed (more suitable for architectural features such as door-jambs and mihrab niches). Living reef coral is easier to cut through and dress to a smooth finish although it did require hardening by exposure to air.

If this article has inspired you about architecture in Bahrain or the use of coral stone, I enthusiastically recommend you to visit the

House for Architectural Heritage in Muharraq that goes into incredible detail regarding the subject.

References:

Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. ISBN 9781134613663.

Lewcock, Ronald (2012). Bahrain Through The Ages. Routledge. ISBN 9781136141782.

Michael, Mika. (2013) "Architecture in Bahrain". Bahrain Guide.

|

| Bonus Coral meme |