The story behind my research on law and legal practice in late imperial Russia is also a story about archives. For me, as someone who had mainly worked with anthropological methods before, the extensive archival research that went into "The Lawful Empire" (for details, click here) was a major change, a change that greatly enhanced my respect for historical work due to the finite nature of sources. In the past, when in doubt, I had returned to the field for more participant observation or focus group interviews and I could always be sure that this would lead to fascinating new data. With archival research, life turned out to be a lot less predictable. Sometimes you discover that one document that (you think) will change the world, only to realize later that its contribution is a lot more modest; and sometimes, you simply don’t find the documents you need. Or you find them with considerable delay, as I will discuss next week in a blog entry on my book’s final chapter.

Research between Kazan, Crimea, and St. Petersburg

What made matters more challenging in my recent project, which documents legal reform and court practice on two of the Russian Empire’s interior peripheries, Crimea and the Volga-Kama region, is that the relevant archives are geographically scattered across the vast Eurasian landmass. The bulk of the research was carried out at the National Archive of the Republic of Tatarstan (NART) in Kazan, about 600km east of Moscow, and at the State Archive of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (GAARK) in Simferopol on the Black Sea peninsula, which during my archival research (2010-2013) was not only de iure but also de facto part of Ukraine. Trips to the two locations were not easily combined; and as it turned out, whenever I entered the field, I stayed in either Kazan or Crimea, never in both. However, as the years passed and the project’s focus became more refined, it also became clear that this regional, bottom-up perspective, as rewarding and innovative as it was, had to be complemented by work at the Russian State Historical Archive (RGIA) in St Petersburg, where the ministry of justice and other key institutions held their records. The point was not so much that this central archive offered a top-down perspective but that its documentation also contained many local voices (either because locals had written to St. Petersburg or because central investigators had conducted enquiries in the regions and taken their results back with them).

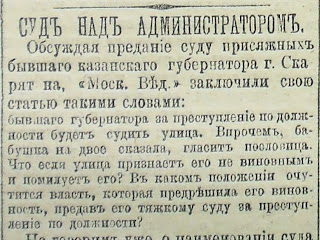

Doing a project in three locations that are thousands of kilometers apart from each other is logistically difficult (and expensive), but also very satisfying because every location and every archive comes with its own challenges and rewards (not to mention quirks). The same is true for the specialized libraries that I used for their collections of newspapers, journals, and other publications, especially the Slavonic Library in Helsinki (priceless because many publications from imperial Russia, to which Finland belonged, are on the shelves and thus easily accessible) and the library of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg (with far easier work conditions than the Russian State Library). Last but not least, the library of Kazan University with its extensive collection of imperial newspapers and its department of ‘rare books’ proved to be incredibly rich. That some of its newspapers were part of heavy folders that no library assistant felt comfortable to lift led me into the basement of the Kazan library stacks, and left alone among those endless shelves of dusty old papers, you could not help but feel excited (I’m an explorer!) and appalled (how on earth did my life end up in this basement?) at the same time. In archives, you quite literally dig deep.

I should add that I have the terrible habit of arriving unannounced, the first reason being that local archives, libraries, and museums tend not to send you away if you are already there (as opposed to telling you by email that they have nothing of interest for your project, which is not always true), and the second and probably more crucial reason being that I am simply not organized enough for doing things differently. I avoid travelling in July and August – when many Eurasian archives are closed – but other than that, I tend to just go and play things by ear.

When I first arrived at the Crimean archive in April 2010, I found the front door locked. An ominous sign told me of a "technical break until further notice". As it turned out, they were rearranging their collections inside, an understandable and necessary endeavor. The following six weeks were still incredibly productive because once I had got hold of an employee and explained the purpose of my stay, they were extremely welcoming and had no objections to me being the only person in the reading room while they were going through their files. In fact, the person in charge of this room, a Crimean Tatar, and I enjoyed countless conversations over the next few weeks, sometimes jointly brooding over old files, sometimes discussing aspects of local history. That the Crimean archive always closed at 1.30pm on Fridays for the entire weekend was a blessing in disguise, for it enabled, in fact encouraged, me to explore this small peninsula and its geography on foot in considerable detail. When the Karaite prayer houses in Evpatoriia on the peninsula’s western shore, the khan’s palace at Bakhchisaray, or the pass across the coastal mountains and the small vineyards and orchards between Alupka and Yalta, exalted by so many nineteenth-century writers, suddenly become alive, you begin to develop a very different relationship with your written sources.

Handwriting, photography, and being back in school

Back at the archive (in both Crimea and Kazan), nineteenth-century handwriting proved to be a particular headache. It was rarely an issue when local litigants or court officials wrote their requests or reports to institutions higher up because they invariably wanted to make a good impression. The response from the center was often far less ceremonious and more difficult to make sense of; it tended to look like scrap paper with indistinct scribbles on them. In both regional archives I therefore spent many hours with the local archivists comparing and identifying individual letters and words, gradually developing a more trained eye for reading such correspondence. I certainly learned never to underestimate how much work you spend on deciphering, rather than just reading files.

Another lesson was always to expect the unexpected. Once the person usually in charge of the Crimean reading room had other business to attend to, and so someone from the administration replaced her for a day. It was a day to remember. “YOU UNPLUG THAT LAPTOP OF YOURS RIGHT NOW, DO YOU HEAR ME?!” was the new supervisor’s way of introducing herself to me. Her face was trembling with anger while I was still trying to work out what the issue was. Then she turned at everyone else in the room. “AND YOU LOT AS WELL! PULL THOSE PLUGS OUT! NOW! DO YOU HAVE ANY IDEA HOW MUCH WE PAY FOR ELECTRICITY?” Actually, we did, as many archives charge you for the use of laptops in Russia and Ukraine. The Crimean archive didn’t. But rather than kindly ask us to make contributions, the administration decided to go for a good old verbal thrashing (which continued for the rest of the day). At 35 years of age, I felt odd to sit there again like a schoolboy. Still, I kept telling myself that at least it wasn’t as tough as Saratov on the Volga River. A colleague of mine had done research there in the middle of February in what turned out to be a tiny archive with very few seats, which forced her to wait in line every day at 7am in minus 20 degrees Celsius to secure a desk. That’s real dedication! And perhaps a good reason for focusing on Russian ties with Africa or Latin America in the next project.

A final note on the conditions that archives offer when it comes to photography. Given the logistical challenges outlined earlier, photography played a crucial role in my project. While the first trips to the different locations were more exploratory and focused on getting an overview of the kinds of sources that existed, follow-up trips tended to be far shorter and more focused. This was facilitated by the fact that both the Crimean and the Kazan archives allowed you to take as many pictures of archival documents as necessary (provided you told them which ones you needed and paid a small fee). From one trip I returned with 1,200 pictures; from another with 800. It was an arrangement that helped foreign researchers, who are more dependent on the visual material you can gather in shorter periods of time. Things were far more regulated (and expensive!) at the central archive in St. Petersburg, where taking time-consuming notes turned out to be the only feasible option. Unfortunately, by now, local rules have also become stricter, with high fees and new rules introduced for photography in Crimea and Kazan. I am not sure that these new rules protect the historical material any better; they certainly impose constraints on researchers who are not constantly in the area.

On the whole, then, my research in "The Lawful Empire" not only offers a snapshot of life and legal practice in late nineteenth-century Crimea and Kazan, but it is itself a snapshot of how historical research was possible in these two regions roughly between 2009 and 2015.

-- Stefan Kirmse