In 1953, Doris Hatch was a 22-year-old girl who lived in the small college town of Cambridge Springs, about 25 miles south of the city of Erie. She was tall, dark-haired, wore glasses, and was generally attractive. She lived with her widowed mother, Mrs. Lucy Hatch, then 54. After graduating from high school Doris had taken a commercial course in Erie before going to work as a clerk in the First National Bank of Cambridge Springs. She also took a local part-time job in Cambridge Springs keeping books for the Park Hardware Store, which was managed by William Ray Turner, a native of Cambridge Springs.

William Turner, a graduate of both the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pennsylvania School of Law, failed the bar exam. He attempted to join the FBI, but failed. During World War II Turner served in the Philippines as a lieutenant in the military police. Turner also worked as a personnel investigator at the Keystone Ordinance Plant in Greenwood Township, Crawford county. Before returning to Cambridge Springs Turner worked for the

Erie Dispatch Herald as a police reporter and editor of the newspaper’s Sunday edition in Erie county.

Monday, July 27, 1953, was a typically warm summer day and Doris’ mother later remembered: “She was wearing an orange organdy dress and white, low-cut shoes.” About 11:00 a.m. Doris received a telephone call at the bank, where she worked, from Turner. “Can you stop over at lunch-time and look up an invoice?” he asked her. At 11:30 a.m. Doris left the bank. She walked across two streets (altogether a couple of hundred feet) to the store. Inside were Turner and two employees, Irving Stanford and Ronnie Caldwell.

Doris looked up the invoice. Meanwhile, Stanford and Caldwell left. Ronnie later recalled, “After she came in, Turner told me, ‘Ronnie, take Stanford out and have lunch.’ ” Caldwell did so, and returned alone a short time later. As he afterwards told it, “Turner was by himself then. About 12:45 p.m. he left, saying he was going to Erie to buy something.”

At 1:00 p.m. with Doris overdue at the bank, a bank official telephoned Mrs. Hatch at her modest frame home several blocks away. “I haven’t seen her,” said the mother. “She should have been home for lunch.” Mrs. Hatch called the hardware store. No one had seen Doris since noon. Mrs. Hatch thought no more of it until that night when Doris still failed to come home. For Doris not to return home, or to call her mother, was unthinkable, according to Mrs. Hatch.

Mrs. Hatch in an interview would recalled the day that her daughter disappeared:

I called Bill Turner and asked him if he knew where Doris was. He said she’d walked out of the store shortly before noon. I told him I was worried and wanted to notify the police. He said that probably wasn't necessary, that she’d be home.

Mrs. Hatch didn't take the advice. She telephoned Police Chief Albert Hutson that night. Hutson, a one-man force, would or could not do much. At 9:00 a.m. the next day Hutson telephoned the state police in Meadville, the Crawford County seat. State troopers, when they got to town, regarded Doris as a run-of-the-mill missing person. They felt that Mrs. Hatch wasn’t cooperative, and ended up with the impression that she was a small town woman who didn't want to broadcast her family troubles for small town gossips. She was even reluctant to let the town’s weekly newspaper print anything on the case.

Two days later, with Doris still not back, a bank director telephoned Raymond Shafer, Crawford County district attorney, and advised him that there might be more to the disappearance than met the eye. Shafer drove in with the county detective and visited Turner, who was well known in town, a deputy constable, and an old acquaintance of the prosecutor. Turner had even once tried to obtain a county detective post himself.

Turner admitted to the district attorney that there was one remark that Doris made when she left his store that day that puzzled him. “On the way out, she said, ‘Goodbye, Bill, thanks for everything.’ I don’t have any idea what she meant by it.” By then it had been established (and has never been disproved) that Turner was the last person to see Doris before she disappeared. Turner was quite cooperative with the police. He explained his theory that he believed that Doris had an unhappy home life and must have fled from it. He willingly supplied information when Mrs. Hatch didn't talk freely.

The state police based a significant portion of their first circular about Doris on Turner's statement, which read:

Miss Hatch is alleged to have led a very dull life at home. Her father was dead and she has been responsible for taking care of her mother, paying the bills and doing most of the housework. She has been very restricted in her social life and was not believed to have been a happy person.

When Mrs. Hatch was asked about this later, she verbally tore that portrait to shreds. “Doris didn't have any

beaux hanging around her, but as far as I know she was happy, She just wasn't a gadabout.” Later editions of the circulars would appeared without the paragraph based on Turner’s statement.

Turner’s assistance, however disputed, was short-lived. On July 31 he left by car for Magnolia, Massachusetts, where his wife and small daughter were vacationing with his wife’s parents. Shafer and the police soon found that there were mysteries in the case, which gave it a very unusual complexion. One troubling aspect was that Doris had not taken anything with her that day to work but the clothes on her back, a pair of shoes in a bag to be repaired, and $30 in her purse. The First National Bank of Cambridge, where Doris was employed, checked her accounts and found them to be in order — Doris had some $700 of her own money deposited, which she’d left untouched.

In mid-November the bank offered a $500 reward for any information as to the whereabouts of Doris. A week later it was raised to $700 when two local men, J.C. Allee, bank president; and George Klandatos, restaurant owner, added a $100 each. The total eventually reaches $8,500 with a generous contribution by the

Erie Daily Times.

For a number of weeks all that one could get out of Cambridge Springs were hints of undue influence in Doris’ disappearance. People were close-mouthed. Late in 1953, according to one man in the community, it was believed that Doris was bumped for knowing too much; not so long before some money had been embezzled from the Park Hardware store. Turner was under routine scrutiny, but an employee made a settlement with the firm after Turner had threatened to have him arrested.

There had been a couple of arson investigations; one about a fire at a property owned by the Turner family. Doris had been one of the people questioned. It wasn't until later that an investigating officer stated, “The state police fire marshal was ready to arrest Turner, but a Crawford County official vetoed it.”

The police wanted to talk to Turner again. But he was still in Massachusetts. While he was gone they made an unsuccessful search of the hardware store, which he and his mother owned jointly. The turning point in the investigation came early in September. Mrs. Hatch and her brother came to Erie County and laid the facts before Captain Frank Milligan, commanding officer, of the state police in northwestern Pennsylvania; they wanted the investigation pushed. That was when Milligan assigned Trooper Lew Penman to the case. Penman was a member of Milligan’s crack criminal investigation detail, a veteran of some 13 years on the force. He didn't have an easy start. Cambridge Springs had become touchy about the Hatch case. On one of his first trips there a prominent citizen asked him belligerently: “What makes you think you’re qualified to investigate a case like this?”

By that time Turner had returned to Cambridge Springs. Shortly afterward, he traded in his 1950 Chevrolet at a garage located next door to his store, which lead to an informant tipping off a state police auto safety inspector that the car ought to be checked. There were two curious things about the car: Turner had supposedly turned down a trade-in offer before his Massachusetts trip and while he was gone he’d installed new seat covers. So the police visited the garage and took a look. What they saw underneath the seat covers prompted them to impound the vehicle and have it towed some 400 miles to the FBI laboratories in Washington, D. C. The photographs of the car’s interior were ugly dark stains throughout. The car was saturated — seats, floor, sides and ceiling. There was a noticeable concentration on the right front seat. The stains were human blood, according to the FBI report. The report also said that there had been an attempt to wash them off.

This was sufficient evidence to invite Turner in for questioning. Turner cooperated — up to a point. His explanation for the blood was that he’d picked up a couple of accident victims and taken them to a hospital. The trouble was that on different occasions his version of the accident location varied. Police patiently checked each version. They could find no accident records and no hospital admissions. Even this didn't explain the blood on the ceiling.

For that, Turner had another answer:

On his Massachusetts trip, he’d cut his right thumb opening a beer can. The blood, he said, spattered as he waved the thumb in the air to stop the bleeding. He displayed a scar on his thumb. At this point, Turner refused to take a lie detector test arranged by Shafer. “After all, I’m not charged with anything,” he replied.

This sort of evidence should shatter a suspects’ composure under interrogation. In most cases it would. But it didn't faze Turner, who was 38 years old in 1953, he was not the stereotypical small town merchant. He came from an excellent family in the community. Having earned a law degree, he worked as a newspaper reporter, even wrote several detective stories, and for a time in Manila was assigned to homicide investigations while serving in the military police; then afterwards, working briefly as a personnel investigator for an ordnance plant, Turner knew and understood the science of interrogation. Turner was no man to be bulldozed into making incriminating statements. He knew as much, or more about law and police work than many of the men he encountered in the case, and that’s what frustrated them. “He knows his rights and he insists on them,” one officer said despairingly.

There were good and bad things to be said for Turner. During his military service he saved a pilot from the wreckage of a plane crash in which he himself was injured. He was decorated for bravery. Some people thought the experience left an unfortunate mark on his mind. His first marriage to an Erie woman in 1940 had broken up. In 1946 he married a nurse he had met in the Army. At some time in his later life he became an alcoholic. Police who checked his habits found that he would consumed as much as a fifth of whiskey a day. He seemed to have a sadistic touch and some of the investigators insisted that he was a psychopath.

A friend of Turner recalled:

One time when he was drinking he decided to show me ‘how we took care of arrests in Manila.’ He twisted my arm behind me and would have broken it if his wife hadn't hit him with a shoe. He didn't know his own strength.

Turner stood six foot three and weighed more than 200 pounds. He was considered brilliant, somewhat egotistical, and manipulative in his relationships with women. Some of the most important evidence being held in reserve indicated that Turner was a philanderer and that one of the girls he had been stringing along was Doris. The extent of their relationship was never completely clarified. But there was reason to believe, police said, that Doris was in love with Turner, no matter what he felt.

Captain Milligan eventually disclosed some of the facts on which this conclusion was based. “Ten days before her disappearance,” he said, “Turner took Doris to Erie to buy her a pair of shoes. Two days later he took her to a baseball game in Cleveland. He was even with her the night before she vanished.” It took two years for Doris’ mother to accept the possibility that these statements were true. She was heard to say before, “I never knew Doris to go out with him. She wasn't a gadabout, and I certainly wouldn't have approved.” Finally, on the second anniversary of her daughter’s disappearance Mrs. Hatch conceded, “I suppose Doris could have been seeing him all that time without my knowing it. He used to drive her home a lot, but I never thought anything about it.” Contrary to rumors, Mrs. Hatch was insistent that Doris was not pregnant in 1953. She added that while she couldn't give up the hope that Doris was alive, “She didn't leave of her own free will.”

It was later learned that at the very time of the disappearance Turner was carrying on a deceptive romance with a woman in Cleveland. He had her convinced that he was an international lawyer working for the State Department. To cover up when he couldn't get away to visit her once, he pretended that he was engaged in secret intelligence work overseas. His ruse was to send a letter to Casablanca and then have it re-mailed to her with proper North African stamps and cancellations — This letter was written the night before July 27, 1953.

Two months after Doris’ disappearance Turner sent $200 to another woman in Denver, Colorado. Questioned about his relationship with Doris, Turner laughed it off, calling her a “good kid” and admitting, “I bought her a few drinks.” This background wasn't known to the general public until after February, 1954, when Harold Sullivan, executive editor of the

Erie Times, invited Turner to his office. He and Turner had covered a beat together years before. Sullivan thought Turner might talk more freely to him. But Turner had the same answers plus a ready retort to all accusations. “Where’s the body?” he wanted to know. “If I’m guilty of anything, let them find the body.” From his legal experience Turner knew the rules of

corpus delicti. Without producing positive evidence that Doris was dead no one could take a step against him.

Penman and the other men who’d worked on the case had compiled plenty of other evidence. Some of it they’d talk about frankly; other parts they’d only hint at. For instance, it was known that Turner was absent for about three and a half hours on the afternoon of Doris’ disappearance. He said he’d been driving the store truck — not the bloodstained car — and had gone to Erie on business. Police checked the places where he said he’d been, but none of his story could be accounted for except by a sales slip from one store. This showed a purchase by the Park Hardware Store (Turner’s store) on that date, but not when or by whom. “The same night,” Penman stated, “someone made a telephone call from the hardware store to the airport at Erie. The airport has no record of its nature.” Turner’s answer was: “I didn't make it, and if I had, I wouldn't tell you.” The fact remained that someone with access to the store must have used the telephone.

Turner couldn't afford to kid about his position in the case when Sullivan broke the story, shortly after his talk with Turner. Within a week, Turner was admitted to the Veterans’ Hospital in Erie suffering from a liver ailment apparently produced by his hard drinking. A day or so later he was stricken with a nervous breakdown and was sent to the state mental hospital, in Warren county. Little was heard of the case until he was released on May 11, 1954. He left with his family to settle in Massachusetts.

Developments were slow. Thousands of circulars on Doris were mailed to police agencies across the nation. An automatic stop was put on all state driver’s license files so that police would be notified if the name Doris Hatch ever appeared. Once it did in Indiana — a different girl. Scores of leads were checked. A grave in a cemetery near Cambridge Springs, which “didn't appear to be settling right,” was examined. The Park Hardware Store, since sold, was searched from the eaves to an old sewer in the basement. One of the new owners stated irritably, “I wish they’d solve it. Every time you write a story people stare in the windows — but they never buy anything.” Some such stories were the targets of caustic counterattacks. A Cambridge Springs newspaperman, who insisted that Doris could just as well be a runaway, or an amnesia victim, as she could be dead, accused the state police of pointing the finger of suspicion at Turner to cover up their own failure to solve the case.

There were other tips. One about a

decaying odor in a nearby county was traced to organic fertilizer. Another was passed along, an equally bad one, from a girl who was convinced she’d seen Doris in a Cleveland diner. But the rewards, along with the contribution from the

Erie Daily Times, expired with no solution in sight.

On November 1, 1955, After two years, three months and six days, the answer was uncovered in a thicket in northern Connecticut by a man who’d set out that day to train his beagle for hunting. Martin Genholt, of Stafford Springs, Connecticut, had turn loose his dog, Queenie, in underbrush just off Route 32, an uninhabited road leading to Massachusetts, which was less than a mile away. Genholt heard the dog thrashing in the leaves 50 or 60 feet off the road. Queenie wouldn't heed his calls. Genholt went in himself. He came to a spot that looked to him, at first glance, to be just a leaf-covered area at the foot of a small tree. When he looked again he discovered that there was a skeleton. Genholt called the state police. They came with the coroner and removed the bones. Nearby they found a fragment of an orange dress, the remains of some white shoes, and a woman’s gold wrist watch.

The discovery at first was just a routine investigation for the local authorities. There were no missing persons reported in the area. But the Pennsylvania state police had a circular on Doris Hatch filed with the Connecticut state police. In a matter of hours the watch was traced back through the manufacturer to a jeweler in Cambridge Springs whose initials were scratched on it. “Yes,” he told the Connecticut authorities on the telephone, “I sold that watch to Doris Hatch.” The next call went to Captain Milligan in Erie county.

The news broke November 2, and reporters were asking Penmen if the watch was enough identification. “Don’t worry,” Penmen said. “We brought Doris’ dental chart along. A dentist just looked at the skeleton’s teeth in Hartford Hospital. It’s Doris, all right.” Penmen went on to say “It looks good. We can tell from successive falls of leaves on the ground that the bones were there at least two years. The location is just 11 miles off Route 20, the main route from Erie county to Massachusetts. But best of all, the pathologist says she was stabbed to death with a sharp, thin instrument — stabbed in the neck, back and right side. You can still see the slices on the bones.” Then Penman smiled, and revealed his next move. “To Massachusetts, to talk to Turner,” he said. “A secret warrant charging him with murder has already been issued in Crawford County.”

That morning Penmen left for Boston where Turner worked as advertising manager for a soft drink machine company. He arrived about noon, and about 2:00 p.m., after a conference with Boston police, Penmen with follow officers went to the company to bring in Turner. At 3:00 p.m. Detective Lieutenant James V. Crowley of the Boston force, who’d accompanied them, returned to police headquarters red-faced with anger. “Somebody telephoned his house this morning with a tip that he was going to be picked up,” Crowley said. “He left the office.” At 3:30 p.m., Penman looking grim, stated “Turner just shot himself to death near his home.” Turner had returned home about 12:30 p.m. and had stopped only long enough to change clothes and pick up a note-pad, pencil, thermos jug of coffee, and a .45-caliber semi-automatic pistol. His wife saw only the coffee. He told her he was going to take a drive and think over his predicament. At 1:15 p.m. an off-duty Manchester policeman saw a car parked near a seawall along the ocean two miles from Turner’s home. Then he saw a man’s head jutting above the wall. He walked over. There was Turner lying dead against the wall with a bullet through his chest. There was a half-drunk cup of coffee nearby.

Turner had written two notes on the pad, both to his wife.

The first read:

Forgive me for what I am about to do. I’m innocent, but I refuse to expect the family to go through this, and of course you. Believe me, it’s better this way. Bill. Get the insurance and my will.

The second, told his wife to write a friend of Turner’s to obtain some letters, which were not concerned with the case.

Neighbors and fellow employees of Turner’s were shocked by the suicide. In the year and a half they’d known him they’d never heard of the Hatch case. To them he was just another commuting executive. Some women in his office cried when they heard the news. But proprietors of newsstands, which he frequented, recalled that he seemed more than usually interested in the news. Every day, they said, he bought every morning and evening Boston newspaper and always managed to scan the important news pages. Back in Cambridge Springs Mrs. Hatch cried with relief. “I’m just happy I lived to know the answer,” she said.

|

| Doris Hatch (1953) |

|

| Mother Lucy Hatch with a photograph of her missing daughter, Doris (1953) |

|

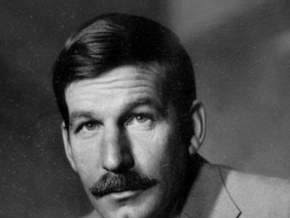

| William Turner (1953) |

|

| Suspect William Turner, 40, dead from self-inflicted gunshot wound (1955) |