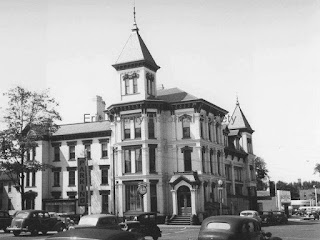

The Downing Insurance Building was a refined structure at 9th and Peach Street. It was built in 1883 by Jerome F. Downing for $40,000, and later demolished for the redevelopment of Downtown Erie.

The interior was in keeping with the exterior, elegantly and conveniently arranged, finished in attractive hard woods, and provided with stained glass windows. The ceilings were a lofty thirty-feet from the floors — tastefully decorated.

The office force comprised some twenty-five clerks and assistants, a number of whom were employed with Mr. Downing from ten to twenty years. The office represented the Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Company, employing over 2,000 local agents with a territory that was comprised of fourteen states and five territories. Agents render their reports under the direction and control of the manager, Mr. Downing.

Born on March 24, 1827, Jerome F. Downing was a native of Enfield, Massachusetts, and a lawyer by profession. He was reared on a farm and educated in the schools of Massachusetts. On reaching adulthood he entered journalism and subsequently was editor-in-chief of the Troy Daily Post in New York State. Having decided to abandon journalism for the law, he became principal of the high school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, studying law while occupying that position, where later he was admitted to the bar in 1855, before moving to Erie that same year.

In Erie he acquired a lucrative law practice and was district attorney of the county in 1863. In 1864 he was offered the Western management of the Insurance Company of North America, which, being disinclined to give up his profession, he accepted with hesitation, and with the stipulation that the headquarters of the department should be at Erie. The management of the Pennsylvania Fire was added in 1872. The connection of these two companies in the West under the direction of Mr. Downing continued until January 1, 1895, when the Pennsylvania Fire withdrew and established an independent western department, and the Philadelphia Underwriters, composed of the Insurance Company of North America and the Fire Association of Philadelphia, the strongest combine of the kind in the world, took the place of the Pennsylvania Fire, and he became manager of its Western Department.

Mr. Downing was also president of the Keystone National Bank; vice-president of the Erie Dime Savings and Loan Company, and a prominent member of the Board of Trade. Also an inventor, he held several patents for his inventions improving the use of chairs.

The interior was in keeping with the exterior, elegantly and conveniently arranged, finished in attractive hard woods, and provided with stained glass windows. The ceilings were a lofty thirty-feet from the floors — tastefully decorated.

The office force comprised some twenty-five clerks and assistants, a number of whom were employed with Mr. Downing from ten to twenty years. The office represented the Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Company, employing over 2,000 local agents with a territory that was comprised of fourteen states and five territories. Agents render their reports under the direction and control of the manager, Mr. Downing.

Born on March 24, 1827, Jerome F. Downing was a native of Enfield, Massachusetts, and a lawyer by profession. He was reared on a farm and educated in the schools of Massachusetts. On reaching adulthood he entered journalism and subsequently was editor-in-chief of the Troy Daily Post in New York State. Having decided to abandon journalism for the law, he became principal of the high school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, studying law while occupying that position, where later he was admitted to the bar in 1855, before moving to Erie that same year.

In Erie he acquired a lucrative law practice and was district attorney of the county in 1863. In 1864 he was offered the Western management of the Insurance Company of North America, which, being disinclined to give up his profession, he accepted with hesitation, and with the stipulation that the headquarters of the department should be at Erie. The management of the Pennsylvania Fire was added in 1872. The connection of these two companies in the West under the direction of Mr. Downing continued until January 1, 1895, when the Pennsylvania Fire withdrew and established an independent western department, and the Philadelphia Underwriters, composed of the Insurance Company of North America and the Fire Association of Philadelphia, the strongest combine of the kind in the world, took the place of the Pennsylvania Fire, and he became manager of its Western Department.

Mr. Downing was also president of the Keystone National Bank; vice-president of the Erie Dime Savings and Loan Company, and a prominent member of the Board of Trade. Also an inventor, he held several patents for his inventions improving the use of chairs.

|

| Downing Insurance Building (1940s) |