|

| Pre-Islamic Arabia |

Arabia, which spans an area of 1.25 million sq. miles, is a rugged, arid, and inhospitable terrain. It consists mainly of a vast desert, with the exception of Yemen on the southeastern tip, a fertile region with ample rain and well suited for agriculture.

The southwestern region of Arabia also has a climate conducive to agriculture. The first mention of the inhabitants of Arabia, or “Aribi,” is seen in the ninth century b.c.e., in Assyrian script. The residents of northern Arabia were nomads who owned camels.

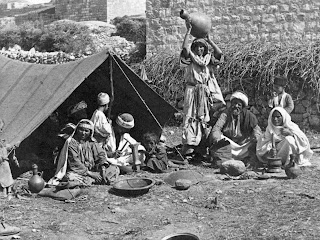

In pre-Islamic Arabia, there was no central political authority, nor was there any central ruling administrative center. Instead, there were only various Bedu (Bedouin) tribes. Individual members of a tribe were loyal to their tribe, rather than to their families.

The Bedu formed nomadic tribes who moved from place to place in order to find green pastures for their camels, sheep, and goats. Oases can be found along the perimeter of the desert, providing water for some plants to grow, especially the ubiquitous date palm.

Since there was a constant shortage of green pastures for their cattle to graze in, the tribes often fought one another over the little fertile land available within Arabia, made possible by the occasional desert springs. Since warfare was a part of everyday live, all men within the tribes had to train as warriors.

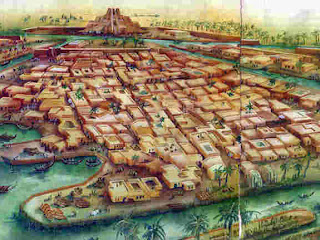

By the seventh century b.c.e. Arabia was divided into about five kingdoms, namely the Ma’in, Saba, Qataban,

Hadramaut

, and Qahtan. These civilizations were built upon a system of agriculture, especially in southern Arabia where the wet climate and fertile soil were suitable for cultivation.

Of the five kingdoms Saba was the most powerful and most developed. Until 300 c.e. the kings of the Saba kingdom consolidated the rest of the kingdoms. Inhabitants of northern Arabia spoke Arabic, while those in the south spoke Sabaic, another Semitic language.

As

Yemen lay along a major trade route, many merchants from the Indian Ocean passed through it in south Arabia. The south was therefore more dominant for more than a millennium as it was more economically successful and contributed much to the wealth of Arabia as a whole.

By the seventh century b.c.e. the oases in Arabia had developed into urban trading centers for the lucrative caravan trade. The agricultural base of Arabia contributed to the economy of Arabia, enabling inhabitants to switch to economic pursuits in luxury goods alongside an ongoing agrarian economy.

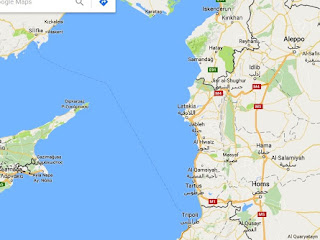

The commercial network in Arabia was facilitated mainly by the caravan trade in Yemen, where goods from the Indian Ocean Basin in the south were transferred on to camel caravans, which then traveled to

Damascus and Gaza.

Arabia dealt in the profitable products of the day—gold, frankincense, and myrrh, as well as other luxury goods. The role of the Bedu, likewise, evolved. Instead of just being military warriors engaged in tribal rivalries, they were now part of the caravan trade, serving as guardians and guides while caravans traveled within Arabia. These Bedu were different from other nomadic tribes, as they tended to settle in one place.

Assyrians, followed by the neo-Babylonians, and the Persians disturbed unity in Arabia. From the third century c.e. the Persian

Sassanids and the Christian Byzantines fought over Arabia. Later on, just before the rise of Islam, there emerged two Christian Arab tribal confederations known as the Ghassanids and the Lakhmid.

The city of Petra in northwest Arabia was under the control of the Byzantines (through the Ghassanids), followed by the Romans, while the northeastern city of Hira fell under Persian influence (the Lakhmid). Under the Lakhmid and Ghassanid dynasties Arab identity developed, as did the Arab language.

The central place of worship for the nomadic Bedu tribes was the Ka’ba, a cubic structure found in the city of Mecca, which houses a black stone, believed to be a piece of meteorite. The Ka’ba was the site of an annual pilgrimage in pre-Islamic Arabia.

Abraham first laid the foundations of the Ka’ba. Over a millennium the function of the Ka’ba had drastically changed and just before the coming of Islam through Muhammad, idols were found within the shrine.

The Bedu prayed to the idols of different gods found within. Although the various nomadic Bedu tribes often formed warring factions, within the sacred space of the Ka’ba, tribal rivalries were often put aside in respect for the place of worship. Mecca became a religious sanctuary and a neutral ground where tribal warfare was put on hold.

By the seventh century c.e., besides being an important religious site, the city of Mecca was also a significant commercial center of caravan trade, because of the rise of south Arabia as a mercantile hub. Merchants of different origins converged in the city.

Just before the rise of Islam, the elite merchants of the Quraysh tribe led Mecca loosely, although it was still difficult to discern a clear form of authoritative government in Mecca. Mecca, like southern Arabia, was home to many different people of various faiths.

Different groups of people had settled in Arabia, especially in the coastal regions of Yemen, where a rich variety of religions had coexisted, having originated from India, Africa, and the rest of the Middle East.

This is because of its strategic location along the merchant trade route from the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. They were Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians who had migrated from the surrounding region.

These migrants were markedly different from the indigenous inhabitants of Arabia in that they adhered to monotheistic faiths, recognizing and worshipping only one God. Thus, the inhabitants of pre-Islamic Arabia were familiar with other monotheistic faiths prior to the coming of Islam, however, subsequent Muslim society would refer to those living in pre-Islamic Arabia as living in jahiliyya, or “ignorance.”