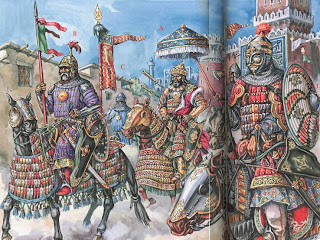

While Mangu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan and third ruler of the Mongol Empire, was conquering China, he sent his brother Hulagu westward to attack the cities of Islam.

In 1256, Hulagu directed his men against the infamous sect of Assassins that had terrorized much of the Middle East since the 11th century. After destroying Alamut, the Assassins’ stronghold, Hulagu then advanced on Baghdad.

Hulagu Khan reached Baghdad and he reprimanded the Caliph for not having supported him in his war against the assassins, thereby breaking oath of allegiance once offered to Genghis Khan.

Mongol reportedly had the support of some Shi’ites interested in the downfall of the Sunni Caliphate.

Hulagu requested that the Caliph open doors of Baghdad to the Mongols. Abbasid caliph al-Mustasim (1242-1258) failed to make proper preparations for the invasion, rejected demands to recognize Mongol authority.

The mighty Caliph – assured of the solidarity of Muslin armies from Maghreb to Cairo and Damascus, and the obstacle to the Mongol invasion presented by the two rivers Euphrates and Tigris - haughtily rebuffed Hulagu’s demand.

Enraged, the Mongols began their siege 0n February 1 and attacked the walls, ramparts and towers defending the city.

After a prolonged assault during which the city was bombarded by the artillery of the time (ballistic missiles like catapults, mortars, and other machines throwing explosives, smoke bombs, grenades and incendiary rockets), Mongol forces stormed into the city on February 15, 1258 and sacked it ruthlessly. The sack of Baghdad turned into a merciless massacre.

Only the Christian churches and palaces were spared from looting and vandalizing. Muslim citizens were slaughtered by the thousands; mosques were defiled, palaces pillaged. For days, the Mongols and their Christian axillaries murdered and plundered, destroying Baghdad’s famous libraries, hospitals, palaces and mosques.

The orgy of looting and killing continued for seventeen days before the city was set ablaze. As many as 100,000 died in the looting of Baghdad.

The captured Caliph and his male heirs were wrapped in carpets or sewn into sacks and then trampled to death by Mongol horses and warriors.

By fallen the city of Baghdad, leaving Mamluk Egypt the last stronghold of Muslim culture.

Mongol invaded Baghdad (Feb. 15, 1258)

In 1256, Hulagu directed his men against the infamous sect of Assassins that had terrorized much of the Middle East since the 11th century. After destroying Alamut, the Assassins’ stronghold, Hulagu then advanced on Baghdad.

Hulagu Khan reached Baghdad and he reprimanded the Caliph for not having supported him in his war against the assassins, thereby breaking oath of allegiance once offered to Genghis Khan.

Mongol reportedly had the support of some Shi’ites interested in the downfall of the Sunni Caliphate.

Hulagu requested that the Caliph open doors of Baghdad to the Mongols. Abbasid caliph al-Mustasim (1242-1258) failed to make proper preparations for the invasion, rejected demands to recognize Mongol authority.

The mighty Caliph – assured of the solidarity of Muslin armies from Maghreb to Cairo and Damascus, and the obstacle to the Mongol invasion presented by the two rivers Euphrates and Tigris - haughtily rebuffed Hulagu’s demand.

Enraged, the Mongols began their siege 0n February 1 and attacked the walls, ramparts and towers defending the city.

After a prolonged assault during which the city was bombarded by the artillery of the time (ballistic missiles like catapults, mortars, and other machines throwing explosives, smoke bombs, grenades and incendiary rockets), Mongol forces stormed into the city on February 15, 1258 and sacked it ruthlessly. The sack of Baghdad turned into a merciless massacre.

Only the Christian churches and palaces were spared from looting and vandalizing. Muslim citizens were slaughtered by the thousands; mosques were defiled, palaces pillaged. For days, the Mongols and their Christian axillaries murdered and plundered, destroying Baghdad’s famous libraries, hospitals, palaces and mosques.

The orgy of looting and killing continued for seventeen days before the city was set ablaze. As many as 100,000 died in the looting of Baghdad.

The captured Caliph and his male heirs were wrapped in carpets or sewn into sacks and then trampled to death by Mongol horses and warriors.

By fallen the city of Baghdad, leaving Mamluk Egypt the last stronghold of Muslim culture.

Mongol invaded Baghdad (Feb. 15, 1258)