|

| Alexander the Great |

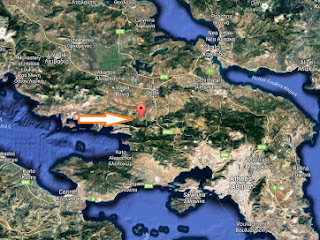

Alexander the Great was born in a town called Pella in the summer of 356 b.c.e. His father was

Philip of Macedon, and his mother was Olympias. Philip II ascended to the throne in 359 b.c.e., at the age of 24. Under Philip II, Macedonia thrived and emerged as a strong power.

Philip reorganized his army into infantry phalanx using a new weapon known as the sarissa, which was a very long (18-foot) spear. This was a devastating force against all other armies using the standard-size spears of the time.

Alexander’s birth and early childhood are unclear, related only by Plutarch, who wrote his Life of Alexander around 100 c.e., many centuries later. In his youth Alexander had a classical education, with Aristotle as one of his teachers. One of his tutors, Lysimachus, promoted Alexander’s identification with the Greek hero Achilles.

Later, Philip II took another wife, Cleopatra, who bore him a son named Caranus and a daughter. This created a second heir to the throne. Olympias was a strong-willed woman who jealously guarded her son’s right to succession. She had given Philip his eldest son, however, she was no longer in favor with Philip.

At the age of 18, Alexander and his father led a cavalry against the armies of Athens and

Thebes, which were fighting the last line of Greek defenses against Philip’s conquest. Philip had set a trap with his maneuver and at the decisive moment, Alexander, with his cavalry, sprung the trap.

This victory at the Battle of Chaeronea in August 338 completed Philip’s conquest of Greece. In 336 Philip was murdered by Pausanias, a bodyguard. Upon the death of his father, Alexander and his mother, Olympias, did away with any of his political rivals who were vying for the throne. Philip’s second wife and children were slain.

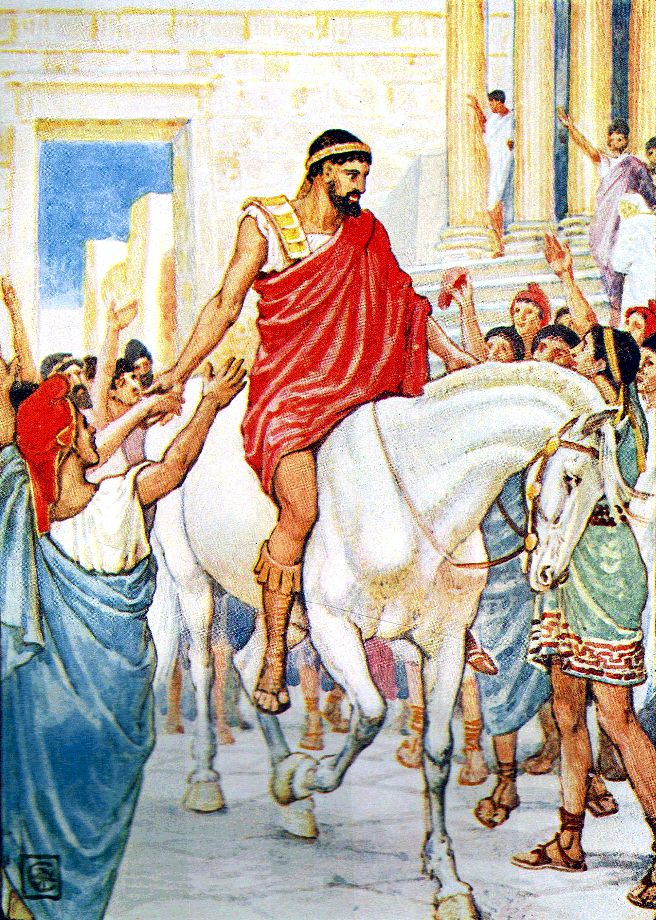

Alexander the KingAlexander became king in 336. He was an absolute ruler in Macedonia and king of the city-states of Athens, Sparta, and Thebes. As a new king, he had to prove that he was as powerful a ruler as his father, Phillip II, had been. Revolts against his rule first occurred in Thrace.

In the spring of 335, Alexander and his army defeated the Thracians and advanced into the Triballian kingdom across the Danube River. Alexander faced the challenge of placating the recently conquered Greek city-states. While Alexander was in the Triballian kingdom, the Greek cities rebelled against the Macedonian rule.

|

| Alexander journey |

The Athenian orator

Demosthenes spread a rumor that Alexander had been fatally wounded in an attack. News of Alexander’s death sparked rebellions in other Greek states, such as Thebes. The Thebans attacked the Macedonian garrison of their city and drove out the Macedonian general Parmenio.

Their victory was due to a Greek mercenary named Memnon of Rhodes. Memnon defeated Parmenio at Magnesia and pushed him back to northwest Asia Minor. Alexander returned to Thebes after his victories and faced strong opposition from the Thebans, but Alexander defeated them swiftly.

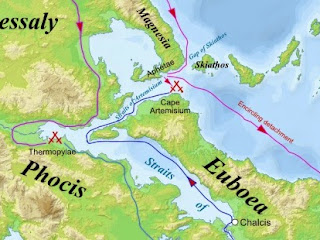

Campaign Against PersiaAlexander embarked on a campaign against Persia in the spring of 334. The Persians had attacked Athens in 480, burning the sacred temples of the Acropolis and enslaving Ionian Greeks. Alexander, a Macedon, won great favor with the Greeks by uniting them against Persia.

He set out with an army of 30,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and a fleet of 120 warships. The core force was the infantry phalanx, with 9,000 men armed with sarissa. The Persian army had about 200,000 men, including Greek mercenaries. Memnon, the Greek mercenary general, led the Persian force.

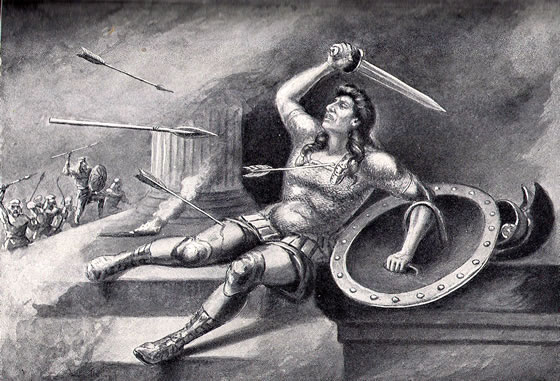

Alexander had an excellent knowledge of Persian war strategy from an early age. In the spring of 334 he crossed the Hellespont (Dardanelles) into Persian territory. The Persian army stationed themselves uphill on a steep, slippery rocky terrain on the eastern bank of the river Granicus. Here they met Alexander’s army for the first time in May 334. Alexander was attacked on all sides but managed to escape, though he was wounded.

The Persians left the battle, thinking they had claimed victory, and left behind only their Greek mercenaries to fight, resulting in a very high casualty rate on the Persian side. Alexander’s armies advanced south along the Ionian coast. Some cities surrendered outright. Greek cities, such as Ephesus, welcomed him as a liberator from the Persians.

Memnon’s forces still presented a threat to Alexander. They stationed themselves at sea, and as Alexander did not wish to join in a sea battle, they were unable to stop his advances on land. In the city of Halicarnassus, Alexander and Memnon met in battle again.

Alexander took the city, burned it down, and installed Ada, his ally, as queen. The Persian cities Termessus, Aspendus, Perge, Selge, and Sagalassus were taken afterward without much difficulty. This ease of conquest continued until he reached Celaenae, where he ordered his general Antigonus to placate the region.

“Divine” Ruler of AsiaThroughout his military campaign people perceived Alexander to be divine. Even the ocean, according to legend, seemed to be servile toward him and his armies. There was a legend involving a massive knot of rope, stating that he who could unravel the knot would rule the world. Many had tried, while Alexander merely cut through the knot with his sword.

Upon hearing this, King Gordius of Gordium surrendered his lands. The story of this divine prophecy being fulfilled spread quickly. Memnon’s death was also regarded as proof of Alexander’s divine quality. This hastened Alexander’s progress through the Persian territories of the eastern Mediterranean, which were long-held, conquered Greek states.

The Battle of Issus in the gulf of Iskanderun was a decisive battle fought in November 333. The Persian king Darius himself led the Persians forces. Darius had a massive force, much larger than Alexander’s army. Darius was brilliant, approaching Alexander’s army from the rear and cutting off the army’s supplies.

The battle occurred on a narrow plain not large enough for the massive armies; it was fought across the steep-sided river Pinarus. This lost the advantage for the Persians, and Alexander emerged victorious as King Darius III fled.

The Battle of Issus was a turning point. Alexander moved from the Greek states that he liberated to lands inhabited by the Persians themselves. He conquered

Byblos and Sidon unopposed. In Tyre he faced real opposition.

The city fortress was on an island in the sea, and his prospects were worsened by his lack of a fleet. To his aid came liberated troops, defected from the Persian fleet. The army and the people of Tyre were defeated—most were tortured and slain, some were sold into slavery. Other coastal cities then readily surrendered.

In 331 Alexander marched on to Egypt. Egyptians welcomed him as he was freeing them from Persian control, and the city of Alexandria was founded in his name. Alexander took a journey across the desert to the temple of Zeus Ammon, where an oracle told him of his future and that he would rule the world. From Egypt, Alexander corresponded with Darius, the Persian king. Darius wanted a truce, but Alexander wanted the whole of the Persian Empire.

The same year he marched into Persia to pursue Darius. He conquered the lands around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Alexander encountered Darius at Gaugamela and defeated the Persian army. Babylon and

Susa fell, and he reaped their riches. After conquering the Persian capital of Persepolis, he rested there for a few months and then continued his pursuit of Darius. However, his own men had already assassinated Darius.

Alexander started to adopt Persian dress and customs in order to combine Greek and Persian culture as a new, larger empire. He married Roxane, creating a queen who was not Greek, and this lost some of his Greek supporters. Still he gathered enough military support to invade India in 327.

After many conquests he encountered Porus, a powerful Indian ruler, who put up a great battle near the river Hydaspes. After this his men were then reluctant to advance further into India. Alexander was seriously injured with a chest wound, and his armies retreated from India.

Alexander died on June 10, 323 b.c.e., at the age of 33. Different scenarios have been proposed for the cause of his death, which include poisoning, illness that followed a drinking party, or a relapse of the malaria he had contracted earlier.

Rumors of his illness circulated among the troops, causing them to be more and more anxious. On June 9, the generals decided to let the soldiers see their king alive one last time, and guests were admitted to his presence one at a time. Because the king was too sick to speak, he just waved his hand. The day after, Alexander was dead.