Plataea was a city of southern Boeotia situated in the plain between Mount Cithaeron and the Asopus river.

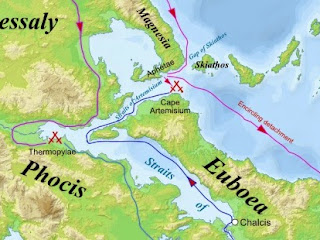

As a result of an attempt by Thebes to force it into the Boeotia Confederacy, the city joined an alliance with Athens in 519 BC. It subsequently provided support to the Athenians against the Persian at Marathon (490), Artemesium and Salamis (480), before being sacked by the Persian in 479.

Plataea was the scene of the great final battle between the Persian forces and the assembled Greek resistance in 479 BC. The two forces met in Boeotia on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron near Plataea.

In this battle a largely Greek force including Helots, defeated the Persian army of Xerxes I, led by Mardonius, brother in law of King Xerxes; the victory marked this battle as the final Persian attempt to invade mainland Greece.

The Persian force numbered about 50,000 men, including 15,000 from northern and central Greece. The Greek army, led by King Pausanias of Sparta, totaled about 40,000 men, including 10,000 Spartans and 8,000 Athenians.

The Persian not only had the advantage in total numbers but also had more cavalry and archers. Two sides faced one another for several days.

Mardonius attempted to force the Greeks to fight on a flat plain, where the Persian cavalry would be most effective. When the Greeks tried to change their position, Mardonius believed they were fleeing.

He attacked but the Greeks proved superior at close quarter fighting. Persian lost and Mardonius was killed.

Causalities are difficult to estimate, but the Persian probably lost about 10,000 non-European warriors and 1000 Medizing Greeks. The Greeks forces suffered causalities of perhaps just over 1000 men.

Battle of Plataea

As a result of an attempt by Thebes to force it into the Boeotia Confederacy, the city joined an alliance with Athens in 519 BC. It subsequently provided support to the Athenians against the Persian at Marathon (490), Artemesium and Salamis (480), before being sacked by the Persian in 479.

Plataea was the scene of the great final battle between the Persian forces and the assembled Greek resistance in 479 BC. The two forces met in Boeotia on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron near Plataea.

In this battle a largely Greek force including Helots, defeated the Persian army of Xerxes I, led by Mardonius, brother in law of King Xerxes; the victory marked this battle as the final Persian attempt to invade mainland Greece.

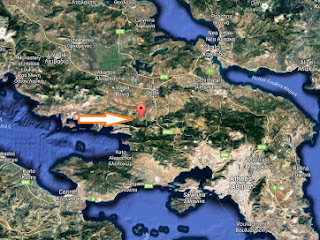

|

| Location of Plataea |

The Persian not only had the advantage in total numbers but also had more cavalry and archers. Two sides faced one another for several days.

Mardonius attempted to force the Greeks to fight on a flat plain, where the Persian cavalry would be most effective. When the Greeks tried to change their position, Mardonius believed they were fleeing.

He attacked but the Greeks proved superior at close quarter fighting. Persian lost and Mardonius was killed.

Causalities are difficult to estimate, but the Persian probably lost about 10,000 non-European warriors and 1000 Medizing Greeks. The Greeks forces suffered causalities of perhaps just over 1000 men.

Battle of Plataea