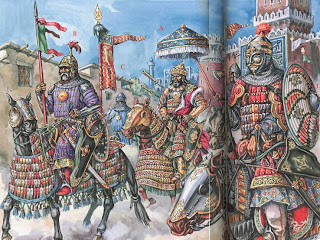

Battle of Ankara is a battle between the Ottomans and the Timurids. The decisive battle of Ankara, or battled of Cubukabad, was fought at Cubukabad near Ankara on July 20, 1402.

Timur (1336-1405), known in the west as Tamerlane, from Samarkand, had founded a vast Eurasian empire stretching from India to Russian.

Regarding himself as the legitimate successor of the Mongol ruler, he considered Bayezid I’s ambition to conquer Muslim states a challenge to his authority.

Sultan Bayezid I led an Ottoman army against a force led by Timur. Bayezid became sultan in 1389 after the assassination of his father Murad on the battlefield at Kosovo.

In battle of Ankara, Bayezid’s army was a hardened and disciplined force of 85,000 men, while Timur commanded between 140,000 and 200,000 men.

The Ottoman troops fought heroically and some 15,000 Turks and Christians are said to have been fallen in the attempt to break the Mongol lines.

When the rest had fled, Bayezid and his rearguard continued to resists far into the night until they were overwhelmed.

Defeated and taken prisoner, Bayezid I was first chivalrously treated by Timur, but later after attempting to escape is said to have been locked up and carried around in an iron cage.

While still in Timur’s custody he died on March 8, 1403, according to some sources by his own.

The Ottoman defeat at the battle of Ankara was a serious blow to the merging new empire, which did not recover until the period of Mehmed II.

Tamerlane vs Bayezid I in Battle of Ankara

Timur (1336-1405), known in the west as Tamerlane, from Samarkand, had founded a vast Eurasian empire stretching from India to Russian.

Regarding himself as the legitimate successor of the Mongol ruler, he considered Bayezid I’s ambition to conquer Muslim states a challenge to his authority.

Sultan Bayezid I led an Ottoman army against a force led by Timur. Bayezid became sultan in 1389 after the assassination of his father Murad on the battlefield at Kosovo.

In battle of Ankara, Bayezid’s army was a hardened and disciplined force of 85,000 men, while Timur commanded between 140,000 and 200,000 men.

The Ottoman troops fought heroically and some 15,000 Turks and Christians are said to have been fallen in the attempt to break the Mongol lines.

When the rest had fled, Bayezid and his rearguard continued to resists far into the night until they were overwhelmed.

Defeated and taken prisoner, Bayezid I was first chivalrously treated by Timur, but later after attempting to escape is said to have been locked up and carried around in an iron cage.

While still in Timur’s custody he died on March 8, 1403, according to some sources by his own.

The Ottoman defeat at the battle of Ankara was a serious blow to the merging new empire, which did not recover until the period of Mehmed II.

Tamerlane vs Bayezid I in Battle of Ankara