|

| Antonine Emperors |

The four Antonine emperors of Rome—Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161 c.e.), Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 c.e.), Lucius Verus (r. 161–169 c.e.), and Commodus (r. 180–192 c.e.)—ruled over a time extending from the height of the Pax Romana to one where the Roman Empire was having increasing difficulty carrying its many burdens.

The founder of the dynasty, Antoninus Pius, was born to a family that already numbered several consuls among its members. He served for many years in the Senate and as Roman official before being adopted as successor to the emperor Hadrian in 138 c.e. Part of the arrangement was that Antoninus would in turn adopt two boys as his heirs. One was the nephew of his wife, Annia Galeria Faustina.

This was Marcus Antoninus, the future Marcus Aurelius. The other was Lucius Verus, the son of Hadrian’s previous choice as successor, Lucius Aelius Caesar. When Hadrian died the same year, Antoninus succeeded peacefully. Antoninus was more than 50 when he became emperor.

|

The reign of Antoninus was marked by peace and by an emphasis on Italy and Roman tradition that broke with the practices of the globetrotting philhellene Hadrian. His dedication to traditionalism was one of the qualities for which the Senate gave him the title of “Pius.” Antoninus also cut back on the heavy spending on public works that had marked Hadrian’s reign.

Antoninus spent most of his time in Rome, by some accounts never leaving Italy during his reign. The 900th anniversary of the city’s legendary founding took place in 147 c.e., and a series of coins and medallions with new designs stressing Rome’s ancient roots were issued to commemorate the occasion. In foreign policy Antoninus preferred peace to war and did not lead armies himself, but the empire waged war successfully on some of its borders.

Antoninus’s death was followed by a dual succession, the first in Roman history. Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius became co-emperors, although Marcus was clearly the dominant partner in the relationship. The new emperors faced many challenges. In the east, the king of Parthia hoped to take advantage of the inexperienced new rulers with an intervention in the buffer state of Armenia.

Marcus sent Lucius, accompanied by a number of Rome’s best generals, to deal with the Parthians. The Parthian war was successful but followed by a devastating plague and pressure from the Germanic peoples across the Danube as the Marcomanni and Quadi actually made it as far as northern Italy.

|

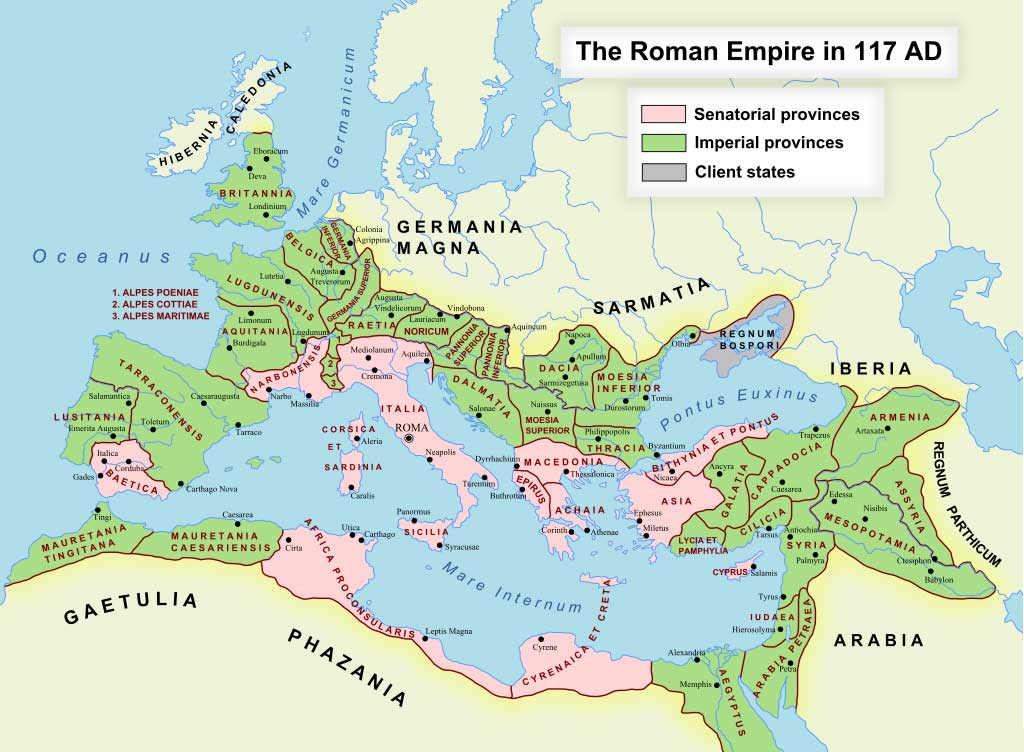

| Map of Roman Empire during Antonine dynasty |

The relationship between the emperors was troubled, as Marcus’s austere dedication to duty clashed with Lucius’s sometimes irresponsible hedonism. Lucius died on campaign against the Germans, however, before any open break could occur, and Marcus referred to him fondly in his Meditations.

Marcus’s long campaigns against the Germans were successful, but he died before he could organize the conquered territories into Roman provinces, and his son and successor Commodus (who received the title of emperor in 177) quickly abandoned his father’s conquests, returning to Rome in order to enjoy the perquisites of empire. Commodus was the first son to succeed his natural father, rather than to be adopted by an emperor, since Domitian.

The hedonistic and exhibitionistic Commodus contrasted with his grim, duty-bound father. His policy of generosity made him popular among Rome’s ordinary people, particularly in the early part of his reign, but the Senate despised him.

|

Commodus was extraordinarily arrogant, renaming the months, the Senate, the Roman people, and even Rome after himself. Unlike Marcus, Commodus had little interest in persecuting Christians, and subsequent Christian historians remembered his reign as a golden age.

In 192 he was removed in the traditional fashion for “bad emperors,” through an assassination plot—the first emperor since Domitian to be assassinated. Commodus left no heirs, and his death marked the end of the Antonine dynasty.