"Agincourt is one of the most instantly and vividly visualized of all epic passages in English history, and one of the most satisfactory to contemplate. It is a victory of the weak over the strong, of the common soldier over the mounted knight, of resolution over bombast, of the desperate, cornered and far from home over the proprietorial and cocksure.....It is a school outing to the Old Vic, Shakespeare is fun..... Laurence Olivier in armour battle; it is an episode to quicken the interest of any schoolboy ever bored by a history lesson, a set-piece demonstration of English moral superiority and a cherished ingredient of a fading national myth. It is also a story of slaughter-yard behavior, and of outright atrocity."

- John Keegan.

With this flowery, but ultimately realistic language, historian John Keegan begins his chapter on Henry V (pictured above) and the Battle of Agincourt in his book "the Face of Battle". Keegan's words are well chosen. For while this battle, which took place on this date in the year 1415 has taken its place in the pantheon of English literature, it was in reality a very brutal and bloody affair. The battle was reported by chroniclers: eye-witnesses to, or reporters of events as gathered in the first hand accounts of participants. And in this case, not only did the victors write the history, but they had the very great fortune of having it immortalized into verse by the greatest dramatist ever to write in their (or any) language. And it was then turned into a couple of movies.... immortality, here we come!!

Why Was Henry V in France?

This battle (Pictured, below in a 15'th Century French miniature), named "Agincourt" after the nearest castle to the battlefield, took place at the end of a long and difficult march for the English army

which had sailed from England on Aug. 11 with eight thousand archers (soldiers who special- ized in the use of the bow and arrow) and two thousand foot soldiers. They had come to retake lands which their King, the young Henry V claimed as belonging to England, but which the French had taken in recent years. They had taken the town of Harfleur at the mouth of the Seine River, near present day Le Havre. But the main body of the French Army was further inland, and waiting for Henry when he tried to march his army through the wet and increasingly cold weather of the autumn season in order to reach the comparative safety of Calais. Henry had to leave a portion of his men behind to hold the captured town. Thus when the English arrived at the site of the battle, their numbers had been reduced to about nine hundred foot soldiers and five thousand archers who had been ravaged by Dysentery (a rabid form of diarrhea), beaten by the cold wind and rain, and were nearly out of food.

Henry's Bedraggled Army Faces France's Magnificent Knights

Facing them across a field of some one thousand yards between two wooded areas was a French Army which was likely five or six times their number, about thirty thousand men. And these were made up mostly of "men at arms"- French cavalry, resplendently

arrayed in full medieval style battle armor, some seventy pounds of steel. These were the cream of France's landed gentry, gentlemen who were high born, and bent upon fighting other gentlemen. They considered the English archers to be a mass of bedraggled peasants who were unworthy of their attention. Also present with the French forces were a smaller, but significant number of foot soldiers who were also armored, though less heavily than the cavalry. This was certainly an impressive force. But the English had a number of key factors in their favor. First, the French forces had been hastily gathered from all around the French lands, and had little or no unified command structure. The English on the other hand were under the command of, indeed were literally fighting alongside of their King, who was able to exercise some overall command through his Lords. In addition, the field across which the armies surveyed each other was newly plowed, and the wet weather of the previous evening had made it a morass of mud. Thus, the very rain which had made the lives of the English army so miserable the preceding night was about to make the lives of the French Army a lot more miserable, and a good deal shorter. And the wooded areas on either side of the field of battle would soon produce a lethal bottle-neck from which there was no escape.

The Battlefield of Agincourt

Beginning at day break, the armies surveyed each other for some four hours. Henry likely was hoping that the French would attack first. But when they didn't, Henry sent his army forward, to about

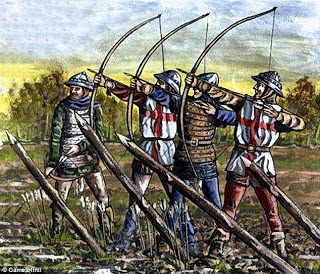

300 yards from the French, with archers mixed in with his foot soldiers, as well as in the woods which (click on the above map to enlarge) bounded the battlefield on each side. The archers in the main line planted their sticks - literally thick wooden posts with sharpened ends into the ground, and pointing forward. Exactly in what configuration and how far apart is not made clear by the chroniclers, but apparently it was in a manner that enabled the archers to stand in front of them, fire several volleys, and then quickly step behind them, thus revealing their presence at a moment too late for the charging horses to be stopped. Exactly how the signal for the archers to commence firing was given is not precisely known. Nevertheless, they fired a volley into the air, all at once - and apparently on command.

The French Knights Charge!!

Just as Henry hoped, this goaded the French into sending their first line forward in a ferocious cavalry charge straight for the English noblemen, disregarding the low-life archers amongst them. The English archers each carried a sheaf or two which had about twenty four arrows, of which they were able to launch one every ten seconds. The French knights in their armor were well

protected from the arrows. But these same chisel-pointed cloth yard arrows, fired one hundred feet into the air returned to earth with sufficient speed to easily pierce the padding on the backs of their horses which were only armored from the front. In addition, these arrows while failing to pierce the armor must have made upon striking their targets a cacophonous noise to the knights who wore it. Coming down as these volleys did literally in clouds this was likely huge factor in confusing the focus of the knights. For, once the archers stepped behind their wooden posts, those horses who had survived the arrows were quickly impaled, and their riders thrown to the ground, from which position their splendid armor became a hindrance making it nearly impossible for them to rise and fight. The English footmen, their nobles, and their archers then moved in and fell upon them, slaying them in great numbers.

The English Make Short Work of the French

Upon seeing this slaughter taking place in front of them, subsequent waves of cavalrymen turned to retreat which sent them straight into waves of foot soldiers trudging forward across the muddy fields to follow up the cavalry. Confusion and panic set in. The Frenchmen and horses at the rear could not see what was happening at the front as they flailed about in the mud. Keegan paints a picture of a three pronged, trident-like formation of attack in which those at the fore of the assault had little room to maneuver on the narrow front, but were being pushed forward into the English foot soldiers by the press of all the confusion

in the rear. And the narrow space of the field with woods on either side left no room to flee to the flanks. The French found themselves bunched in with little or no room to effectively wield their weapons, while being pushed forward into their foes. Those who fell, either wounded or dead, piled upon one another in stacks described by one of the chroniclers as being "as high as a man." This is probably a poetic exaggeration, but the piles of the fallen definitely posed yet another lethal obstruction in a field that was rapidly becoming clogged with them. The resultant butchery left the French with wildly disproportionate casualties - about ten thousand to only one hundred Englishmen killed or wounded.

Shakespeare Makes the Battle Into a Legend

These facts of smashing a large French force by a much smaller English army would seem to guarantee immortality for the struggle. And indeed it was well remembered by a nation who would continue to see and fight the French as their natural enemies for nearly five centuries after. But Henry V himself would die of a sudden illness merely seven years later at the young age of 35. His successors, who possessed none of his strength either of character or conviction, would lose his hard-won gains in France. Nevertheless in the hands of William Shakespeare, writing over 180 years later, the battle achieved mythic status. And this has been imprinted into the memories of countless theater goers, as well as cinema fans in film versions of Shakespeare's play by Sir Laurence Olivier in 1944, and by Kenneth Brannagh in 1989.

One of the chron- iclers writes that upon seeing the huge French force arrayed against them, one of Henry's lords, Sir Arthur Hungerford said: "I would that we had ten thousand more good English archers who would gladly be with us here today!" To which King Henry is recorded as replying: "Thou speakest as a fool! By the God of Heaven, on whose grace I lean, I would not have one more even if I could... He can bring down the pride of these Frenchmen who so boast of their numbers and their strength." Under the brilliant pen of Skakespeare, these fairly straightforward remarks became one of the most stirring speeches ever written:

(Click on the highlighted words to see a video of the speech)

"This day is call'd the feast of Crispian.*

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when this day is nam'd,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say 'To-morrow is Saint Crispian.'

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say 'These wounds I had on Crispian's day.'

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he'll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words-

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester-

Be in their flowing cups freshly rememb'red.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered-

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now-a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day."

- "Henry V", Act 4, Scene 3.

* = Saints Crispin and Crispinian are the Christian patron saints of cobblers, tanners, and leather workers. Born to a noble Roman family in the 3rd century AD, Saints Crispin and Crispinian, twin brothers, were executed by Rictus Varus, the governor of Belgic Gaul, in 286. The feast day of Saints Crispin and Crispinian is celebrated on October 25. In Shakespeare, Crispinian's name is spelled Crispian, which likely conformed to Elizabethan pronunciation, and also fit Shakespeares'

Iambic pentameter form.

READERS!! If you would like to comment on this, or any "Today in History" posting, I would love to hear from you!! You can either sign up to be a member of this blog and post a comment in the space provided below, or you can simply e-mail me directly at: krustybassist@gmail.com. I seem to be getting hits on this site all over the world, so please do write and let me know how you like what I'm writing (or not!)!!

Sources:

"The Face of Battle" - John Keegan Barnes & Noble Inc. / Viking Penguin Inc., 1993,

pp. 79 - 115.

"Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies" Edited by Mark C. Carnes Henry Holt & Co., Inc., New York, 1995, pp. 48 - 53.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Crispin%27s_Day

+ 268.

+ 168.