When announcement came that the slave-holding States had inaugurated civil war, the people of Erie County were practically unanimous in the sentiment that the Union must be preserved. Party differences were forgotten, for the time being, and men of all shades of politics were united together in acts of patriotism. The national flag was displayed from hundreds of buildings, and in all the towns and villages vast and enthusiastic meetings were held to declare in favor of sustaining the Government. Amid the general patriotism, none were more earnest and active than the ministers of the Gospel, who, as a class, allowed no opportunity to pass by which they might advance the cause of the Union. The church, as a body, was warmly enlisted on the side of the Government, and did quite as much in its way, as any other instrumentality, in firing the public heart, inducing volunteering and building up a solemn faith in the ultimate triumph of the national army.

The first war meeting in the county was held in Wayne Hall, Erie, on the 26th of April, 1861. It was very largely attended, and was presided over by William A. Galbraith, one of the leading Democrats of the Northwest. Speeches were made, in addition to Mr. Galbraith's, by George H. Cutler, John H. Walker and George W. DeCamp. A movement had already been started by Captain John W. McLane to organize a regiment to serve for three months. Volunteers were flocking to McLane's standard with surprising rapidity, and it was necessary to raise a fund for the support of the families of many of those who had enlisted. The sum of $7,000 for the purpose was subscribed at the meeting, which was increased in a few days to $17,000. The amount allowed to the needy out of this fund was $3.50 per week to the wife of each volunteer, and 50 cents per week for each of his children. Similar meetings were held in almost every town in the county, and volunteer relief funds were subscribed everywhere. The speakers in most general demand were Messrs. Galbraith and DeCamp.

The 1st Regiment

The camp of the three months' regiment was established on a piece of vacant ground in Erie at the southeast corner of Parade and Sixth streets, where volunteers poured in from all parts of the northwest. More offered in a few days than could be accepted, and many were reluctantly compelled to return home. As a sample of the spirit of the time, the borough and township of Waterford sent forward nearly 100 men. Five companies were recruited in Erie alone, but of these fully one-half were from other places. It was considered a privilege to be accepted, and those who failed to pass muster or arrived too late were grievously disappointed. The regiment left Erie for Pittsburgh at 2 P. M. on Wednesday, the 1st of May, being accompanied by Mehl's Brass Band. A vast crowd was at the railroad depot to witness its departure, and many affecting farewell scenes were witnessed. The regiment reached Pittsburgh at 9 A. M. the next day, and took up its quarters in Camp Wilkins. A number of its members were discharged because the companies to which they were attached exceeded their quota. On the 5th of May, the regiment was presented with a camp flag by the ladies of Pittsburgh, in the presence of 10,000 spectators. It received arms and uniforms on the 29th of May, and was carefully drilled every day that it remained in camp. For some reason, the regiment was never called into active service, and it returned to Erie on Saturday evening, July 20. An immense concourse welcomed the soldiers at the railroad depot, and escorted them to the West Park, where a public supper had been prepared by the ladies of the city. But one member died during the absence of the regiment,

The 83rd Regiment

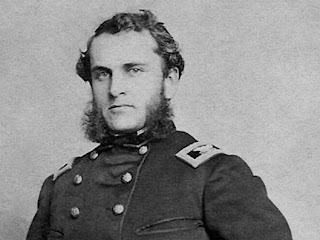

In the meantime, the President had issued a call for 300,000 men for the war, and Colonel McLane had made a tender of a regiment for that service. Many of the members of the three months' regiment had volunteered to go with the Colonel, and they were accordingly dismissed until the 1st of August to await an answer to his proffer. On the 24th of July, Colonel McLane received an order authorizing him to recruit a new regiment. Those of the First Regiment who had re-enlisted were recalled, and recruiting began actively throughout the northwestern counties. The 83d regiment, composed principally of men from the counties of Erie, Crawford, Warren, Venango and Mercer, rendezvoused at Camp McLane, about two miles east of the City of Erie, and was mustered into service between July 29 and September 8, 1861, for three years, where the men were enlisted by Captain J.B. Bell, of the regular army.

While these measures were in progress, Captains Gregg and Bell, of the United States Army, opened a recruiting office in the city for the regular cavalry, and enlisted a considerable number of young men. The Perry Artillery Company, an Erie military organization, offered its services to the Government, and were accepted, with C.F. Mueller as Captain, and William F. Luetje as First Lieutenant.

An immense meeting was held in Farrar Hall, on the 24th of August, to assist in raising men for McLane's regiment. It was addressed by William A. Galbraith, James C. Marshall, George W. DeCamp, Col. McLane, Miles W. Caughey and Capt. John Graham. Meetings of a like character followed throughout the county. The principal speakers besides those named were Alfred King, Strong Vincent, William S. Lane, Morrow B. Lowry and Dan Rice. The harmonious feeling of the time is best illustrated by the statement that the Democrats and Republicans united in a Union pole-raising in Greenfield.

Simultaneously with the efforts in behalf of the new regiment, recruiting was going on with great vigor for the navy. Some sixty persons from Erie went to New York to serve under the command of lieutenant T.H. Stevens. Up to September 7, Captain Carter, of the United States steamer Michigan, had enlisted 700 seamen, who were forwarded in squads to the seaboard.

By September, the Ladies' Aid Society had been organized in Erie to furnish relief to the sick and wounded soldiers in the field, with branches in most of the towns in the county. It was maintained during the entire war, and did invaluable service. Through its labors, boxes of delicacies, hospital supplies, medicines and other comforts for the sick were forwarded to the front almost daily.

The regiment of Colonel McLane, on being reported full, was ordered to the front, and left for Harrisburg on the 16th of September. Its departure was attended by the same vast outpouring and marked by the same pathetic incidents as before, and none who were eye-witnesses will ever forget the scenes of the day. A flag was presented to it on the part of the State December 21, and it became officially known as the Eighty-third Regiment.

The 111st Regiment

Before the departure of the Eighty-third Regiment, Major M. Schlaudecker, of Erie, commenced recruiting for another, adopting the same place for his camp that had been occupied by Colonel McLane's command. Enlistments went on with such alacrity that the regiment left for the front on Tuesday, the 25th of February, 1862, at 2:30 P. M., with every company full. At Harrisburg, it was presented by Governor Curtin with a stand of colors, and took rank as the One Hundred and Eleventh Regiment. It is not necessary to say that the scenes at its departure from Erie were fully as affecting as those before stated. The regiment was accompanied by Zimmerman's Brass Band.

Among the important events in the early part of the year 1862 were the rumors of a war with Great Britain, and the projected naval depot on the lake, in anticipation of the same. A committee of citizens was sent on to Washington by the City Council, to urge the adoption of Erie as the site for the proposed establishment. On the 8th of January, the entire crew of the United States steamer Michigan was ordered to other points, with the exception of eight officers and men. March 8, the newspapers were notified by the Secretary of War that the publication of army movements would not be permitted. A meeting was held in Erie on the 12th of April to provide for the relief of those who might be wounded in the battles that were daily expected in Virginia. Considerable money was raised, and committees were appointed to furnish attendants for those who might need their services. By this date, the country was having war in earnest. Bodies of rebel prisoners were taken through on the Lake Shore Railroad every few days. It might be supposed that war matters absorbed the whole of public attention, but this was only the case in a general sense. All lines of trade and manufacture were carried on with unabated energy during the entire conflict, and a course of public lectures was maintained in the city each winter, comprising some of the most noted orators of the day.

The news of the battles around Richmond, in which the Eighty-third suffered terribly and Colonel McLane was killed, reached Erie in the latter part of June, and caused great mourning. Emblems of sorrow for the dead were placed on many buildings, and hospital stores were hastily sent forward for the wounded.

The 145th Regiment

Early in July the President called for 300,000 more troops, and of this number it was announced that Erie County's proportion was five companies of 100 men each. A meeting to encourage enlistments was held in Wayne Hall, at which the County Commissioners were asked to appropriate $100,000 toward equipping a new regiment. This was succeeded by others, both in Erie and in the country districts. The martial spirit had been much cooled by the disasters in Virginia, and it began to be necessary to offer extra inducements to volunteers. Erie City offered a bounty of $50 to each recruit and the various townships hastened to imitate its example. Another call for 300,000 men decided the County Commissioners to appropriate $25,000 to pay an additional bounty of the same amount. In August, for the third time, the fair grounds were turned into a military camp, and the organization of the One Hundred and Forty-fifth Regiment began. Recruits came forward rapidly, and the regiment left for the seat of war on the 11th of September.

At the same time that enlistments were in progress for the last-named regiment, volunteers were being gathered for other organizations. The navy was receiving numerous accessions, mainly from Erie. Captains Lennon, Miles and Roberts were each raising a cavalry company. It was officially reported that two hundred men had entered the navy from Erie City alone, up to the 16th of August.

The First Draft

Notwithstanding the large number of volunteers, the quota of Erie County, under the various calls of the President, was still short, and a draft seemed inevitable. The papers were full of articles urging the people, for the credit of the county, to avoid the draft, and meetings were constantly being held to induce volunteering. Many persons were badly scared over the probability of being forced into the service, and a few quietly took up their abode in Canada. As the chance of a draft became more certain, insurance companies were formed for the protection of the members. Those who joined these organizations paid a sum varying from $20 to $50, which was placed in a common fund, to procure substitutes for such of their number as might be drawn from the wheel of fate. While preparations for the draft were in progress, recruiting for both the army and the navy went on with great energy. On September 25, Captain Lennon's cavalry company left with full ranks, and by the 4th of October, Roberts' and Miles' companies were both in camp at Pittsburgh.

Toward the latter part of September, the State authorities became alarmed for the safety of Harrisburg, and a hasty call was issued for minutemen to assist in the defense of the capital. Six companies, including some of the leading business men, left Erie for Harrisburg, in response to the Governor's appeal, but, happily, were not needed to take part in any fighting. They returned in the beginning of October, far from pleased with their brief lesson in military duty.

Meanwhile, an enrollment of the militia had been made, preliminary to the draft, under the direction of I.B. Gara, who had been appointed a Commissioner for the purpose. These proceedings, as well as the subsequent measures in connection with the subject, were carried on under the State militia law, the Federal Government not having yet taken the matter into its hands. W.P. Gilson was appointed a Deputy Marshal to prevent the escape of persons liable to conscription into Canada. The officers to manage the draft were B.B.Vincent, Commissioner, and Charles Brandes, Surgeon. Governor Curtin gave notice that volunteers for nine months would be accepted up to the day of drafting.

The draft was held in the grand jury room of the court house on the 16th of October, 1,055 names being drawn for the whole county, the owners of which were to serve for nine months. A blindfolded man drew the slips from the wheel, which were read as they came out to the crowd in attendance in and around the court house. There were many funny incidents, and some that were very sad indeed. North East and Springfield were the only districts in the county that escaped the draft, their quotas being full. In filling the wheel, all persons were exempted above the age of forty-five years; also, all ministers, school teachers and school directors.

After the draft, the main business for some weeks was hunting up substitutes. The price of these ranged from $50 to $250, though the average was in the neighborhood of $150. The act released parties from military service on payment of $300, and those who were able to raise the money generally availed themselves of the privilege. A good many persons who had concluded that the war was to be a long and bloody one, shrewdly put substitutes into the service for a term of three years. Swindlers were plenty, who hired out as substitutes, got their money in advance and then left for parts unknown. Some 300 persons were exempted for physical disability, about 250 failed to report, and, altogether, it is doubtful whether 500 of the drafted men ever went into the army. The first lot of conscripts, fifty-one in number, left for camp at Pittsburgh in the latter part of October, some 300 were forwarded on the 10th of November, and the balance went on at intervals between that and the end of the year. Andrew Scott was appointed a Provost Marshal to hunt up the delinquents, but hardly found enough to pay for the trouble. The Councils of Erie voted $45,000 for the relief of the families of conscripts from the city, and the Ladies' Aid Society supplied each family with a Thanksgiving dinner at its place of residence. A majority of the conscripts reached home by the ensuing August. Few saw any fighting and the number of deaths was quite meager.

Other Matters

By fall prices had gone up 25 to 40 per cent, with a steady tendency to advance. The National tax law was in full operation, and county, city and township levies were largely increased to provide money for bounties. Gold and silver had disappeared from circulation, and national treasury notes, or greenbacks, as they came to be known, were slowly finding their way into use, but the principal medium of exchange still consisted of the notes of uncertain State banks, county and city scrip and Government fractional currency or shin plasters. Even of the latter there were not enough for public convenience, and business men resorted to cheeks and due bills for fractional parts of a dollar. To meet the demand for small change, the city issued scrip in sums of 5, 10, 20, 25 and 50 cents, which proved of much convenience for the time being.

While this was the state of affairs financially, political feeling grew daily more intense. The term Copperhead, as applied to the Democrats, came into use about the beginning of 1863, and the latter, to retort upon the Republicans, styled them Blacksnakes, Revolutionists, Radicals and other names more forcible than polite. The Republicans taunted the Democrats with being opposed to the war, and the latter answered by saying that the Republicans aimed at the destruction of the people's liberty. Looking at the subject now, the embittered partisanship of the day seems supremely foolish and incomprehensible. There were true patriots on both sides, and both parties doubtless contained men who were more anxious for the triumph of selfish ends than of or the good of the country. The mass of the people were patriotic, no matter by what party name they called themselves.

The Second Draft

Early in the year 1863, Congress passed an act taking the matter of conscription out of the hands of the States, rendering all persons liable between the ages of twenty and forty-five, except such as were exempt from physical causes, or for other special reasons, and making each Congressional district a military district, under the supervision of a Provost Marshal, an Enrolling Commissioner and an Examining Surgeon, to be appointed by the President. To escape military duty, when called upon, it was made necessary to prove exemption, furnish a substitute or pay $300. Lieutenant Colonel H.S. Campbell, late of the Eighty-third Regiment, was named as Marshal; Jerome Powell, of Elk County, as Commissioner; and Dr. John Mackim of Jefferson County, as Surgeon, to act for this Congressional district. Headquarters were established at Waterford, and a new enrollment was made during the months of May and June. In the prosecution of their duties, the enrolling officers met with some hostility among the laborers and mechanics of the city, but nothing occurred of a serious nature. The Government was now enlisting Negroes into the army, and bodies of those troops passed through Erie frequently.

The news of the rebel invasion of Pennsylvania, and of the battles at Gettysburg caused a wonderful commotion throughout the county. The Governor made an urgent appeal for militia to defend the State, and instant measures were taken in response. A vast meeting was held in Erie on the evening of June 15, at which earnest speeches were made by Messrs. Lowry, Sill, Galbraith, Walker, Marvin, McCreary and others, pointing out the duty of the people to drive the enemy from the soil of Pennsylvania. About 400 citizens enlisted for the State defense, but, on reaching Pittsburgh, they were ordered home, the victory of Meade having rendered their immediate service unnecessary. Generous contributions of hospital stores were sent to the wounded Erie County soldiers at Gettysburg by the efforts of the Ladies' Aid Society. The fall of Vicksburg and Meade's triumph were celebrated in Erie with great rejoicing.

By reference to the newspapers of the day, we find that in June, Captain Mueller was in Erie recruiting another battery. Large numbers of young men were shipping in the navy. The citizens were making extraordinary exertions to avert another draft. Insurance companies against the draft were formed by the score, and hundreds of persons were putting in claims for exemption to the enrolling officers. Eastern regiments were passing through the city as often as two or three a week, on their way home to fill up their ranks. Not a few liable to military service were slipping off to Canada, and an occasional instance was reported of young men cunningly maiming themselves to secure exemption. The only portion of the male population who felt really comfortable were the deformed, the crippled and the over-aged.

The second draft in numerical order, and the first under the United States law, occurred at Waterford, under the supervision of the officers above named, on Monday and Tuesday, the 24th and 25th of August. The wheel stood on a platform in front of the Provost Marshal's office, and the names were drawn by a blind man. An audience of a thousand or more surrounded the officers, one of whom took each slip as it came out of the wheel and read it aloud, so that all present could hear. The crowd was good natured throughout the proceedings, but many a man who assumed indifference when his name was drawn was at heart sick and sore. The saddest features of the case did not appear to the public; they were only known to the parents, the wives and the children of the conscripts. It is impossible to state the number who were drafted, but as the county was announced to be nearly 1,400 short of its quota a week or so before, it is probable that it did not fall much below that figure. The price of substitutes ran up to $300, with the supply quite up to the demand. On the 26th of September, it was stated in the newspapers that eighty-three of the conscripts had furnished substitutes, 245 had paid commutation, 706 had been exempted and 127 had been forwarded to camp at Pittsburgh.

The fall election for Governor was one of the most exciting in the history of State politics. Meetings were held in all parts of the county by both parties, and much bad feeling prevailed.

Lively Recruiting

In October, appeared a call from President Lincoln for 300,000 more men.

On the heels of this, Governor Curtin announced Pennsylvania's quota to be 38,268, which he asked to be made up by volunteering. A general bounty of $402 was offered to veterans who should re-enlist, and $100 less to new recruits. To this sum the county added $300, and most of the districts $50 to $100 more.

During a portion of the season, the United States steamer Michigan, which had been fully manned again, was guarding Johnson Island, in the upper part of the lake, where about two thousand rebel prisoners were confined, whom rumor accused of a design to escape. In the month of November, reports became current of a proposed rebel invasion from Canada, Erie being named as the landing place. This was the most startling news, in a local sense, that had yet arisen out of the war, and our citizens were correspondingly agitated. While the excitement was at its height, 600 troops arrived from Pittsburgh, with a battery, all under the command of Major General Brooks. The latter directed entrenchments to be thrown up on the blockhouse bluff, and called upon the Citizens to lend him their assistance. Something like one thousand obeyed his summons, with picks and shovels, on the first day, but the workers dwindled woefully in number on the second day. The rumor, which was absurd from the start, soon proved to be false, the work was abandoned, and the troops left for the South in a few days, with the exception of the battery.

The encouragement given by the large bounties did much to promote volunteering. Erie County's quota of the new call was 673, which it was determined by the public should be made up without a draft. On the 14th of January, 1864, the members of the One Hundred and Eleventh Regiment came home to recruit their ranks. They were given a grand reception at the depot, and treated by the ladies to a sumptuous repast in Wayne Hall. The regiment went into camp on the fair grounds, and remained until February 25, when they left for the seat of war with ranks nearly full. A good many members of the Eighty-third Regiment, whose terms had expired, also came home in January, and were received with the cordiality their bravery entitled them to. Seventy-five more arrived on the 4th of March.

Among the features at the beginning of 1864, it is to be noted that two recruiting officers for the regular army were busy at work in the city. The national currency had supplanted all other paper circulation, and, being issued in vast amounts, had inflated prices to twice and thrice their normal standard. A remarkable speculation had commenced in real estate. Sixty persons had enlisted from Erie in the navy and hosts of others were thinking of doing the same in preference to entering the army. Several squads of negro soldiers passed through Erie from Waterford, where they had been accepted to apply on the quota of the county. Five or six criminals were released from prison by the court at the May session on condition that they must join the army.

To the joy of all, when the day for the draft arrived, Erie County escaped, her proportion having been raised. A few names were drawn, however, for the other counties of the Congressional district.

Half A Million More

The call of the President, in July, for 500,000 more men, was succeeded by the usual periodical endeavor to avoid the draft, which had become the all-exciting topic of discussion. At a meeting in Erie, $20,000 was subscribed to offer extra inducements to volunteers, besides the United States, county and district bounties. The quota of the county was stated to be 1,289, and of this, the city's proportion was about one hundred and fifty. Provost Marshal Campbell, in pursuance of instructions, gave notice that Negroes would be taken as substitutes. This hint was eagerly accepted, and Asa Battles, John W. Halderman and Richard M. Broas were deputed to go to the Southwest and pick up recruits to apply on the quota of Erie County. Meanwhile Ensign Bone had opened an office in the city, where he was shipping men by the hundred for the navy. About a thousand entered the service through that channel, receiving an average bounty of $400. The price of substitutes had increased to $550, $600 and $700.

President Lincoln was re-elected in November, after a contest which has never been surpassed in the hatred it engendered, and the vigor with which it was fought on both sides. Every speaker who could be mustered was forced upon the stump, and there was scarcely a cross-roads that did not have its mass meetings, pole raisings and political clubs. The great processions of the two parties in Erie during that campaign were the chief events of a life-time to many of the participants. Notwithstanding the heated canvas, the election passed off without a disturbance, and the defeated party acquiesced in the result with the calmness of a martyr.

On the 10th of November, there were two companies of home guards in Erie organized especially for State defense.

Nearing The End

The call for 300,000 more men in January, 1865, led the Councils of Erie to increase their offer of a bounty to $150, which was ultimately increased to $400. A draft took place at Ridgway, where the Provost Marshal's office had been moved from Waterford, on the 6th of March, in which 2,010 names were drawn from Erie County. The only district that did not have to contribute was Girard Borough. The names of the conscripts were telegraphed to Erie and read to the anxious thousands in waiting, from a window of the Wright Block. Occasionally, a sound of forced laughter would be heard as some excitable person's name was announced, but the general bearing of the crowd was solemn and painful. Hundreds of women were in the crowd, and their distress upon learning of the conscription of some father, husband or brother was most pitiful. The people were at last face to face with war's sternest and cruelest realities. The Legislature had passed an act authorizing any district to pay a bounty of $400, and large sums were now offered for volunteers and substitutes. The price of the latter at one period rose to $1,500, but got down finally to an average of between $700 and $800. Of the drafted men, a good portion entered the service and were mostly assigned to guard duty in the forts at and near Washington. The majority of them were back by the close of June.

On Sunday, April 9, came the glad news of the surrender of General Lee, which was everywhere hailed as the virtual end of the war. The demonstration in Erie over the event was the most joyful and impressive in the city's history. Cannons were fired, bells were rung, flags were thrown to the breeze, and the whole population shouted themselves hoarse for the Union and its gallant soldiers. The illumination in the evening made the streets almost as bright as the noonday sun.

This universal gladness was quickly changed to profound sorrow by the assassination of President Lincoln on that dreadful Friday, the 14th of April. Emblems of mourning instantly took the place of the tokens of victory, and every warehouse, shop and business establishment was closed on Saturday. The special train bearing the martyred President's remains to Springfield, passed through the City of Erie on the 28th of April at 2:50 A.M. There was no particular demonstration gathered at the depot to pay their last tribute of respect to the president.