|

| Diadochi |

Diadochi is the Greek word for “successors” and refers the successors of the empire of Alexander the Great. At first there was initial agreement to the unity of the empire, but this soon turned into wars between rival rulers. These included Macedon, Egypt under Ptolemy as Africa, and the Near East under Seleucus as Asia.

Death of Alexander The GreatAlexander the Great died on June 11, 323 b.c.e., in Babylon. His leading generals met in discussion. Alexander had a half brother, Arridaeus, but he was illegitimate and an epileptic and thought unfit to rule. Perdiccas, general of the cavalry, stated that Alexander’s wife, Roxane, was pregnant.

If a boy was born, then he would become king. Alexander had named Perdiccas successor as regent, until the child was of age. The other generals opposed this idea. Nearchus, commander of the navy, pointed out that Alexander had a three-year-old son, Heracles, with his former concubine Barsine.

The other generals opposed this because Nearchus was married to Barsine’s daughter and related to the young possible king. Ptolemy wanted a joint leadership and deemed that the empire needed firm government and jointly the generals could assure this. Some thought that a collective leadership could lead to a division of the empire.

Meleager, the commander of the pikemen, opposed the idea. He wanted Arridaeus as king to unite the empire. The final decision was to appoint Perdiccas as regent for Arridaeus, who would become Philip III, and if Roxane gave birth to a boy, he would take precedence and become King Alexander IV.

Alexander’s father, Philip of Macedon, had led his armies south and conquered all of Greece. Alexander was king of Macedon and Greece and had left a general there to rule. The Greeks saw that Alexander and his generals had taken on the customs of their hated enemies, the Persians.

The people of Athens and other Greek cities staged revolts as soon as they heard that Alexander had died. Antipater led forces south and battled in what would became the Lamian War.

Craterus arrived with reinforcements. Craterus led the Macedonians to victory against the Greeks at the Battle of Crannon on September 5, 322 b.c.e. As the Macedonians captured Athens, Demosthenes, the leader of the revolt, died by taking poison.

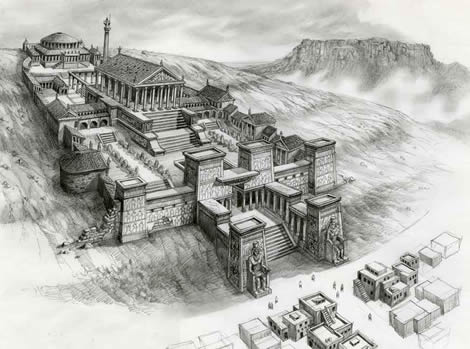

First Diadoch WarPerdiccas ruled as regent, and there was peace for a time. His first war was with Ariarathes, who ruled in Cappadocia in the central part of modern-day

Turkey. The First Diadoch War broke out in 322 b.c.e., when Craterus and Antipater in Macedonia refused to follow the orders of Perdiccas. Knowing that war would come, the Macedonians allied with Ptolemy of Egypt.

Perdiccas invaded Egypt and tried to cross the Nile, but many of his men were swept away. When Perdiccas called together his commanders Peithon, Antigenes, and Seleucus for a new war strategy, they instead killed him and ended the civil war. They offered to make Ptolemy the regent of the empire, but he was content with Egypt and declined.

Ptolemy suggested that Peithon be regent, which annoyed Antipater of Macedon. Negotiations were held and succession was finally decided: Antipater became regent; Roxane’s son, who had just been born, was named Alexander IV. They would live in Macedonia, where Antipater would rule the empire.

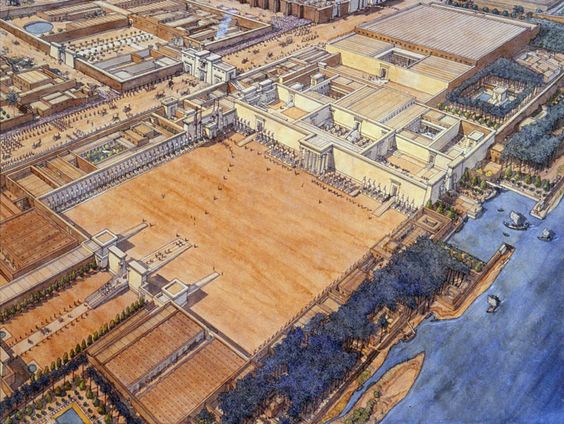

His ally Lysimachus would rule Thrace, and Ptolemy would remain satrap of Egypt. Of Perdiccas’s commanders, Seleucus would become satrap of Babylonia, and Peithon would rule Media. Antigonus, in charge of the army of Perdiccas, was in control of Asia Minor.

Second Diadoch WarWar was again initiated when Antipater died in 319 b.c.e. He had appointed a general called Polyperchon to succeed him as regent. At this, his son, Cassander, organized a rebellion against Polyperchon.

With war breaking out Ptolemy had his eye on Syria, which had historically belonged to Egypt. There was an alliance between Cassander, Ptolemy, and Antigonus of Asia Minor, who had designs against the new ruler Polyperchon. Ptolemy then attacked Syria.

Polyperchon, desperate for allies, offered the Greek cities the possibility of autonomy, but this did not gain him many troops. Cassander invaded Macedonia but was defeated. During this fighting the mother of Alexander, Olympias, was executed in 316 b.c.e.

Polyperchon had the support of Eumenes, an important Macedonian general. Polyperchon attempted to ally with Seleucus of Babylon. Seleucus refused, and the satraps of the eastern provinces decided not to be involved.

Antigonus, in June 316 b.c.e., moved into Persia and engaged the forces of Eumenes at the Battle of Paraitacene, which was indecisive. Another battle near Gabae, where the fighting was also indecisive, led to the murder of Eumenes at the end of the fighting.

This left Antigonus in control of all of the Asian part of the former empire. To cement his hold over the empire, he invited Peithon of Media and then had him executed. Seleucus, seeing that he would no longer have control over Babylon, fled to Egypt.

Third Diadoch WarAntigonus Monophthalmus was now powerful and had control of Asia. Worried about an invasion of Egypt, Ptolemy started plotting with Lysimachus of Thrace and Cassander of Macedonia. Together they demanded that Antigonus hand over the royal treasury he had seized and hand back many of his lands.

He refused, and in 314 b.c.e. war broke out. Antigonus attacked Syria and tried to capture Phoenicia. He lay siege to the city of Tyre for 15 months. Meanwhile, Seleucus took Cyprus.

On the diplomatic front Antigonus demanded that Cassander explain how Olympias had died and what had happened to Alexander IV and his mother, in whose name Cassander held rule. Antigonus made an alliance with Polyperchon, who held southern Greece.

|

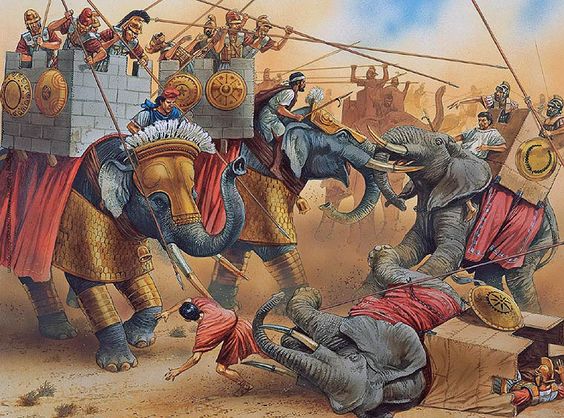

| Demetrius’ Agema fighting Ptolemy’s Companions at Gaza, 312 BC |

Ptolemy sent his navy to attack Cilicia, the south coast of what is now Turkey, in the summer of 312 b.c.e. With his forces in Syria, Ptolemy worried that Egypt might be attacked and retreated.

Seleucus, who was a commander in the Ptolemaic army, marched to Babylon and was recognized as satrap in mid-311 b.c.e.; the previous satrap, Peithon, was killed at Gaza.

Antigonus realized that he could not defeat Ptolemy and his allies. A truce was agreed to in December 311 b.c.e. Cassander held Macedonia until Alexander IV came of age six years later; Lysimachus kept Thrace and the Chersonese (modern-day Gallipoli); Ptolemy had Egypt, Palestine, and Cyprus; Antigonus held Asia Minor; and Seleucus gained everything east of the river Euphrates to India. The following year (310 b.c.e.), Cassander murdered both the young Alexander IV and his mother, Roxane.

Peace lasted until 308 b.c.e. when Demetrius, a son of Antigonus, attacked Cyprus at the Battle of Salamis. He then attacked Greece, where he captured Athens and many other cities and then marched on Ptolemy. Antigonus sent Nicanor against Bablyon, but Seleucus defeated him.

Seleucus used this opportunity to capture Ecbatana, the capital of Nicanor. Antigonus then sent Demetrius against Seleucus, and he besieged Babylon. Eventually, the forces of Antigonus and Seleucus met on the battlefield.

Seleucus ordered a predawn attack and forced Antigonus to retreat to Syria. Seleucus sent troops ahead, but with little threat from the West he attacked Bactria and northern India. When Antigonus attacked Syria and headed to Egypt, his column was attacked by the troops sent by Seleucus.

Fourth Diadoch WarIn 307 b.c.e. the Fourth Diadoch War broke out. Antigonus was facing a powerful Seleucus to his east and Ptolemy to the south. Egypt was secure with the protection of a large navy. Ptolemy attacked Greece, motivated largely by a desire to ensure that Athens and other cities did not support Antigonus.

Demetrius in a diversion attacked Cyprus and continued with his siege of Salamis. This pulled Ptolemy out of Greece, and his navy headed to Cyprus. Ptolemy lost many of his men and ships. Menelaus surrendered Cyprus in 306 b.c.e., once again giving Antigonus control of the city.

Antigonus proclaimed himself successor to Alexander the Great. Antigonus did not view Seleucus as a threat, so instead marched against Ptolemy. His army ran out of supplies and was forced to withdraw. Demetrius had attacked the island of Rhodes, held by Ptolemy.

Ptolemy was able to supply Rhodes from the sea, and so Demetrius withdrew. Cassander, then attacked Athens. In 301 b.c.e. Cassander, aided by Lysimachus, invaded Asia Minor, fighting the army of Antigonus and Demetrius, with Cassander capturing Sardis and Ephesus.

Hearing that Antigonus was leading an army, Cassander withdrew to Ipsus, near Phrygia, and asked Ptolemy and Seleucus for support. Ptolemy heard a rumor that Cassander had been defeated and withdrew to Egypt.

Seleucus realized that this might be the opportunity to destroy Antigonus. Earlier he had concluded a peace agreement with King Chandragupta II, in the Indus Valley, and had been given a large number of war elephants. Seleucus marched to support Cassander.

Hearing of his approach, Antigonus sent an army to Babylon hoping to divert Seleucus. Seleucus marched his men to Ipsus and joined Lysimachus. There, in 301 b.c.e., a large battle ensued. Seleucus, with his elephants, launched a massive attack that won the battle.

Antigonus was killed on the battlefield, but Demetrius escaped. This left Seleucus and Lysimachus in control of the whole of Asia Minor. Seleucus and Lysimachus agreed that Cassander would be king of Macedonia, but he died the following year.

Demetrius had escaped to Greece, attacking Macedonia and, seven years later, killed a son of Cassander. A new ruler had emerged, Pyrrhus of Epirus, an ally of Ptolemy. He attacked Macedonia and the forces of Demetrius.

Demetrius repelled the attack and was nominated as king of Macedonia but had to give up Cilicia and Cyprus. Ptolemy urged on Pyrrhus, who attacked Macedonia in 286 b.c.e. and drove Demetrius from the kingdom, aided by an internal revolt.

Demetrius fled from Europe in 286 b.c.e. With his men he attacked Sardis again. Lysimachus and Seleucus attacked him, and Demetrius surrendered and was taken prisoner by Seleucus. He later died in prison.

This left Lysimachus and Pyrrhus fighting for possession of Europe, while Ptolemy and Seleucus owned rest of the former empire. Ptolemy abdicated to his son Ptolemy Philadelphus. An older son, Ptolemy Keraunos, sought help from Seleucus to try to take over Egypt. Ptolemy died in January 282 b.c.e. In 281 b.c.e.

Ptolemy Keraunos, decided that it would be easier to take Macedonia rather than to attack Egypt. He and Seleucus attacked Lysimachus, killing him at the Battle of Corus in February 281 b.c.e. Ptolemy Keraunos then returned to Asia, and prior to leaving for Macedonia again in 280 b.c.e., he murdered Seleucus.

By the end of the Diadochi wars, Antigonus Gonatas, the son of Demetrius, ruled Greece; Ptolemy II Philadelphus was king of Egypt; and Antiochus I, son of Seleucus, ruled much of western Asia. Ptolemy Keraunos held the lands of Lysander in Thrace. The Diadochi wars came to an end with the death of Seleucus, but wars between the kingdoms continued.