|

| Map of Yamato state |

The Yamato court is known as the birthplace of the Japanese political state. It is a term applied to the political system of the Kofun period but also its development and refinement in the late fifth to seventh centuries c.e. The Yamato state unified north Kyushu, Shikoku, and southern Honshu.

The people were a clan-, or kinship- (uji), based society, where religion played an important part in controlling their lives, but during the Kofun period (the name given to the large key-shaped burial mounds of the time) powerful clan leaders and their families started to emerge as the stratifi cation of communities evolved within the late

Yayoi culture. Small kingdoms were established, each ruled by a different clan.

The rulers at this time were mainly religious figureheads using the people’s faith to govern them. One of the most powerful was the Yamato clan, and after continual warfare among the different kingdoms a union of states developed—the Yamato state, under the rule of the Yamato clan.

In the fourth century c.e. the Yamato were situated in the rich agricultural region around the modern city of Kyoto. In the fifth century, when the Yamato court reached its peak, there was a shift in the power base to the provinces of Kawachi and Izumi (modern Osaka).

The emergence of such powerful clans is evidenced by the increased elaboration of their burial mounds in comparison with the Yayoi period. Burial sites in the Kofun period illustrated a segregating of the workers and elite of the community.

The burial mounds took on a new shape, a "keyhole" design, were larger in size, and were surrounded by moats. By the fifth century it was evident that the power of the Yamato clan had increased. These huge tombs represented the power of the Yamato aristocracy, holding swords, arrowheads, tools, armor, and all the signs of military might.

|

| The burial mounds took on a new shape, a "keyhole" design |

Only religious and ceremonial items had been placed in earlier burial mounds. As Yamato had increased the contact with mainland Asia, the items in the burial tombs reflected their power and influence. Besides the military items, there were such things as gilt bronze shoes and gold and silver ornaments.

The Yamato clan and its strongest allies formed the aristocracy of the Yamato state, occupying the most important positions in the court. A hereditary ruler headed the Yamato court, and because intermarriage within clans produced a large family network, there were constant struggles for power.

Believing that they were descendants of the sun goddess, the Yamato clan developed the notion of kingship and thus began the imperial dynasty. An emperor, based on the Chinese system, represented it. The first legendary emperor of Japan was Jimmu. The emperor, the supreme religious symbol of the state, had no real political power. The power base lay with the clan leaders, headed by a prime ministerstyle official.

These officials had very close ties with the ruler, showing the importance that was placed on the harmony between religion and the governing of the people. There was also economic and military support from the occupational groups within the court known as be.

|

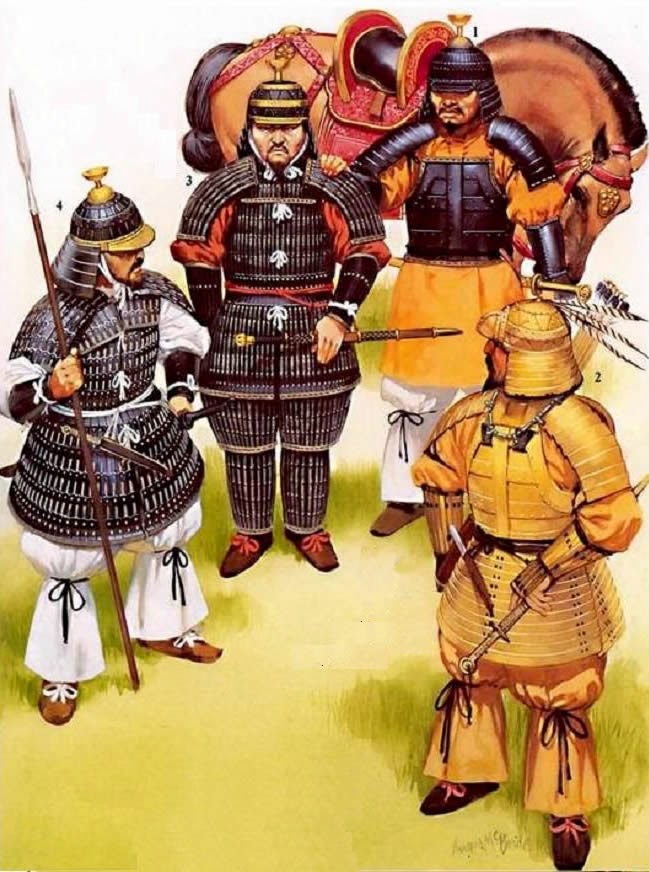

| Heavy military of Yamato clans |

These groups consisted of rice farmers, weavers, potters, artisans, military armorers, and specialists in religious ceremonies. They were subordinate to the ruling families. One group of be were especially important to the ruling family as they consisted of highly skilled immigrants from mainland Asia, who specialized in iron working and raising horses.

The Yamato court became the unifying force in Japan. They began to limit the power of the lesser clan leaders and started to acquire agricultural lands to be controlled by a central body.

A bureaucratic ranking system was developed when the separate kingdoms were incorporated into the Yamato court, and the stronger clan leaders were given titles to reflect their status as regional chiefs. The two titles bestowed on the chiefs were muraji and omi.

The greatest of the chiefs lived at the court and as a collective ruled over the productive lands and hence the farming communities. This also gave them access to large resources of manpower to be used in such activities as burial mound building and also as conscripted troops for the military forays into the Korean Peninsula.

By the fourth century the Yamato court was developed enough to send envoys to mainland Asia, sometimes military, but mostly to gain knowledge of the political and cultural aspects of the far more advanced Chinese and Korean civilizations. They also procured supplies of iron resources said to be plentiful in the south of Korea.

By the end of the fourth and in the beginning of the fifth centuries the military were involved in the expansion of Yamato power throughout the Korean peninsula. At the same time Korea was going through cultural and political changes, with warring between the three kingdoms, Koguryo (north), Paekche (east), and Silla (west).

Alliances were made with the Paekche, against the Silla, with Yamato gaining some power in the region. However, in the sixth century Silla became more powerful militarily, causing Yamato to face power reversals in the region and forcing them to withdraw from the peninsula.

Paekche began to exchange knowledge and resources with the Yamato; scribes, sword smiths, horsemen, and horses were introduced to the court. The Yamato court had a large number of mainland scholars brought over for their advanced knowledge and skills.

The Paekche court also sent a Confucian scholar, a Buddhist scholar, Buddhist scriptures, and an image of the Buddha. These scholars dramatically altered the fast-developing Japanese culture.

Scholars were sent to China to learn about their political and cultural ideals, and in the sixth or seventh century they were brought back to the Yamato court to establish a written system based on Chinese characters and the grounding for the establishment of a parliamentary system. Based on Chinese models of government, the Yamato court developed a central administrative and imperial court.

The sixth century saw the Soga clan’s rise to power. The

Soga clan, which did not claim to be descended from the gods, had entrenched themselves in the Yamato court by establishing marital connections with the imperial family. As well as having administrative and fiscal skills, this allowed them considerable influence within the court structure.

They introduced fiscal policies based on Chinese systems and established the first treasury. They collected, stored, and paid for goods produced by employees. The Soga introduced to the court the idea that the Korean peninsula could be used as a trade route rather than for military conquest.

The powerful Soga clan was in favor of the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, but in the beginning the Soga found opposition from other clans, such as the Nakatomi, who performed the Shinto rituals at the court, and the Mononabe, who wanted the military aspect of the court to be maintained and elevated in importance.

Conflicts arose between the clans, with Soga vowing to build a temple and encourage the spread of Buddhism as the main instrument of worship if successful in battle. They were successful, and there were several Buddhist temples built, and

Buddhism became a strong religion in Japan. The Soga believed that the teachings of Buddhism would lead to a more peaceful and safe society.

The intermarriage of the Soga with the imperial family paved the way for Soga Umako (Soga Chieftain) to install his nephew as emperor, later assassinate him, and replace him with Empress Suiko. Unfortunately, Empress Suiko, was a puppet for Soga Umako and

Prince Regent Shotoku Taishi. A system of 12 ranks was established, making it possible to elevate the status of officials based on merit rather than birth right.

|

| Prince Regent Shotoku Taishi |

Prince Regent Shotoku Taishi was a devout Buddhist and a scholar of

Confucian principles. Under his instigation Confucian models of rank and etiquette were introduced, and he introduced the Chinese calendar. He built numerous Buddhist temples, had court chronicles written, and established diplomatic links with China.

However, with the deaths of Prince Regent Shotoku Taishi, Soga Umako, and Empress Suiko, there was a coup to gain succession to the imperial throne. The coup was led by Prince Naka and Nakatomi Kamatari, who introduced the

Taika (Great Change) Reforms, which established the system of social, fiscal, and administrative codes based on the ritsuryo system of China.

The reforms were aimed at strengthening the emperor’s power over his subjects and not leaving the fi nal decisions to his cabinet. These reforms ushered in the decline of the Yamato court by lessening the control of the court clans over the agricultural lands and the occupational groups.

The reforms abolished the hereditary titles for the clan leaders and instead of them advising the emperor there would be ministries. The new order wanted to have control over all of Japan and make the people subjects of the throne. There were taxes placed on the harvests, and the country was divided into provinces headed by court-appointed governors.