A recent article in the Washington Post titled "

Texas Officials: Schools should teach that slavery was 'side issue to Civil War" has, once again, shed light on a very old fight taking place on the core issues of the United States Civil War. Historians almost across the board agree that slavery was the core issue of the U.S. Civil War, those that disagree will normally acknowledge that the "states right" that was being fought over was slavery. I will touch on that, later in this post, but I first wanted to express in a more general tone why, to my eye, this particular issue on the interpretation of the U.S. Civil War is so critical and is still so violently fought over.

Since the close of the U.S. Civil War in 1865, and with the termination of Reconstruction in the late 1880s, the United States has seen a general move by its southern states, and portions of the northern states, to embrace the U.S. Civil War as a fight over the "Lost Cause." This is a romanticized view of the U.S. Civil War, a re-imagining of the conflict as a battle fought by an outmatched foe (the South) against an aggressive dominating rival (the North.) This view of the U.S. Civil War pivots the narrative into one of the Southern states fighting to defend more morally palatable issues for the United States of the 1880s forwards, issues of limited government, Constitutional balance, and yes, states rights.

States rights reaches to the issue of federalism, the balance between the states and the central federal government, and has been an issue of contention in the United States since its founding. The initial divide between our two political parties reflects this, it is a divide which is rooted in the current debates shaping the United States today.

At its root the "Lost Cause" view of the U.S. Civil War was an effort to remake the war into something more noble. It was also part of an effort by the north and south to reunify the country and close still strong sectional divisions in the early 20th century. As part of this effort both sides agreed to a tacit cultural agreement, northern historians and cultural figures would accept the "nobility" of the southern cause and support that position, and southern historians and cultural figures would embrace Abraham Lincoln and the northern actions as necessary if regrettable. I will admit this is just my opinion but I believe it was this compromise that really put an end to the idea that states had a moral right of secession as a mainstream theory about the U.S. Civil War, most people today may debate the legality of secession and when it could happen, but they've accepted the U.S. Civil War was necessary because it kept the United States a strong nation.

This compromise reached its height, in my opinion, in 1958 with the passage of U.S. Public Law 85-425 which granted the widows of Confederate forces the right to a pension from the U.S. government. The actual law is limited to just this but it has since been taken in common culture as a taciturn recognition of Confederate veterans as having the same status as veterans of the U.S. armed forces in general. For the purposes of this post the actual legality of that view is irrelevant, what matters is that since 1958 the accepted

image of Confederate veterans in the south is that they were patriots, equal to U.S. veterans, not traitors or criminals.

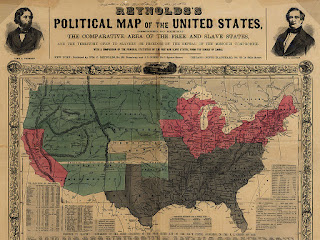

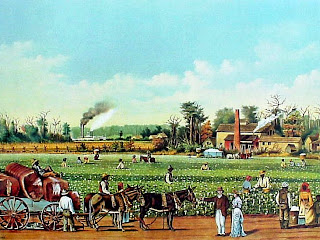

But was the U.S. Civil War about slavery at its core? Bottom line, yes, and also state's rights, and also regional power. To see this though you have to go back to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which dealt with how to handle new states entering the U.S. The issue was the admission of Missouri, whose residents wanted to own slaves. The challenge was that the balance of power in the U.S. Senate balanced evenly between slave states and free states in 1820. This balance of power was considered vital for the southern states because the more populous north dominated the House of Representatives and with the northern states there was growing resistance to slavery. (Not due to any particularly strong moral issues, although that was part of it, rather to a blend of moral issues with good old-fashioned economic concerns.)

To deal with this Maine was admitted at the same time, as a free state, and the U.S. Congress drew a line across the lands of the Louisiana purchase marking off where slavery would end. Both sides also understood that newly admitted states would have to maintain the Senate balance of power between slave states and free states. To offset that balance was unacceptable to both sides - to the north loss of the Senate would make them bound to an unfair "slave power" in the U.S., which had economic interests violently opposed to the growing interests of northern industrial powers. For southern states loss of the Senate would make them vulnerable to pressures that would harm their economic interests as a trading power engaged in a fiercely competitive global agricultural trade.

This balance remained in place until Stephen Douglas in 1854, in part of a bid to improve his political position in a run for the Presidency, in part to open land for railroad settlement, and also due to his political convictions came up with a new plan - scrap the Missouri Compromise and let the residents of each state decide if they wanted to be free or slave. Hence the creation, and passage, of the Kansas-Nebraska Act which said "you local residents, you decide among yourselves if you want to be slave or free."

Now if slavery was not, by itself, a burning issue with deep roots to sectional conflicts, state position, and deeply held ethnic tensions in the United States, you might imagine that this would have been settled in a calm, collected manner. It was not.

The image above is a "free state" poster regarding Kansas - give it a look - as you can see people were quite touchy on the issue of if Kansas would be a slave or free state. Both sides on the issue flooded the territory with individuals and the issue was resolved with armed force. This period was, and is, referred to as "Bleeding Kansas" and it basically pitted "free territory" settlers against individuals from Missouri who came to ensure that slavery would be allowed to expand into Kansas. The situation wasn't really resolved until 1861 when Kansas was admitted as a free state to the union. (By which point things had already reached the "Holy Hell" stage with South Carolina already pulling out of the United States.)

Allow me to close with this point - slavery as an issue in the United States from its founding through 1865 was a contentious issue, both on its own merits and for what it symbolized to the people of the United States. From the 1850s onward though it became probably the central issue of United States politics, for better or for worse. From the rise of the Republican Party out of the dead remains of the Whig Party, a new political organization with an avowed goal of shattering slavery in the United States ideally and at a minimum containing it in the southern states till it died out on its own against Southern leaders who with the Dred Scott decision made it clear they intended to bring slavery into free states and use the power of the federal courts to make slavery a default acceptable option throughout the United States.

If I had to summarize it I'd say that the U.S. Civil War was about slavery because it was a war about what shape the United States would take, what sort of nation it would be - one with slavery or one without. Because within that issue was tied a whole host of other issues of what the United States would be:

- Predominately a strong agricultural exporter power with low tariffs or a strong industrial power with high tariffs and limited foreign trade

- A nation with a strictly enforced racial hierarchy empowered by law or one in which the racial hierarchy was more fluid

- A nation in which private property was sacrosanct or one in which the federal government had the right to redefine, seize, and modify property based on Congressional laws

- A nation in which the federal government or the individual state governments would hold the strongest position of power

It is an ugly truth today but in the end it all really did come down to the issue of...slavery

Sources: Wikipedia articles on

Bleeding Kansas,

Lost Cause,

Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the

Missouri Compromise