|

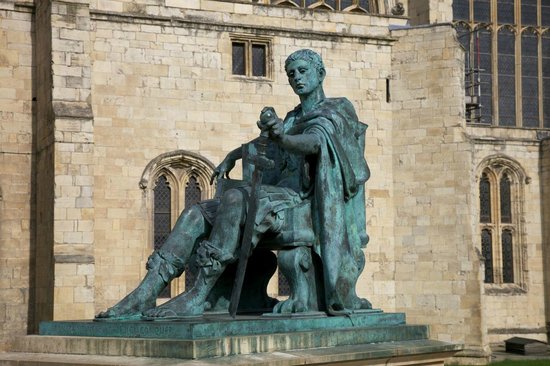

| Constantine the Great |

The reign of Constantine the Great marked the transition from the ancient

Roman Empire to medieval Europe and a decisive step in the establishment of the Christian Church as the official religion for the Greek and Latin civilizations.

His view of church-state relations affected the way that European governments were constituted for centuries, and his influence had direct repercussions on the administration of such countries as Russia, ruled by czars, even until the 20th century.

Constantine was the son of Constantius and Helena. His father was appointed in 293 c.e. as one of four co-emperors in the

Tetrarchy set up by Diocletian. Diocletian chose to keep Constantius’s son under surveillance as his tribune. When Diocletian retired in 305, Constantine was allowed to join his father on campaign in Scotland. His father died in Britain, and his troops proclaimed Constantine as their new Caesar .

Between 305 and 312 Constantine marshaled propaganda, troops, and resources toward taking sole power in the Western Roman Empire. He won a string of battles against the Franks and others and then marched into the Italian Peninsula with an eye on defeating his Roman rival. The key to his

success was a risky battle fought outside Rome in 312.

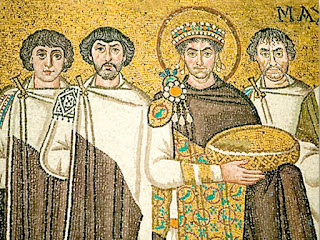

Constantine claims to have seen a celestial vision there that revealed his fortune and steeled his courage. At first he said that it was the appearance of his protector god

Apollo who promised him 30 years of success, with the Roman numeral XXX appearing in the sky. As Constantine grew older, he decided that this visitation was of a Christian nature and that he saw a single cross with the words in hoc signo vince (“in this sign conquer”).

The later Christian version of the story finishes with Constantine’s army marching to victory, the cross emblazoned on their shields. The place of the vision was the Milvian Bridge, now associated with the turning point of his life, his career, and the destiny of the Christian religion. Constantine thought the hand of the divine was on him, and eventually he identified the god as Christian.

As a result, he began to be proactive in his support of the heretofore-persecuted faith. He restored properties to churches in the West and especially showed favor to the clergy. He met his Eastern Roman Empire counterpart and forged an agreement called the

Edict of Milan in 313 c.e., in which the Christian faith was officially permitted.

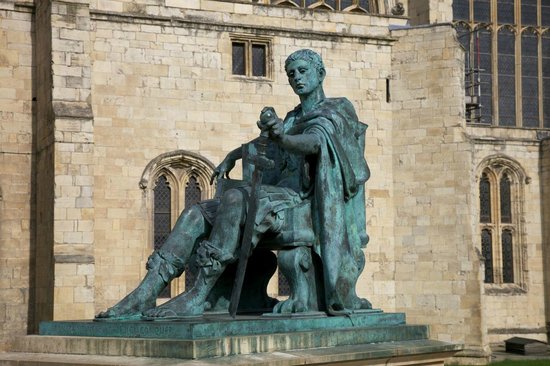

|

| Constantine statue |

Though Constantine is portrayed as the matchless defender of the Christian faith by popularized histories, this interpretation must be taken with a grain of salt. For example, in his decrees he avoided citing specific religions or religious terms, thus he said “Supreme Sovereign” or “Highest God.” He did not require that his subjects do “superstitious” (i.e., Christian) practices to show their allegiance to the empire. He kept a specialist in Neoplatonism as a personal adviser.

He did not officially persecute the Greco-Roman cults, apart from a few police actions. He warned Christians against taking law into their own hands in their zeal to shut down pagan shrines. He dedicated his capital city with both pagan and Christian rites and imported into the city many works of art from pagan temples.

He continued the pagan Roman tradition that the emperor was the divinely appointed mediator between the divine and the empire, thus he intervened infrequently in church disputes. In fact, he did not formally enter the church through baptism until on his deathbed, reflecting his own anxieties about the impossibilities of living a life of holiness while serving as emperor.

East-West DiscordThe concord with the eastern emperor did not last. In the East there was widespread mistrust of Constantine and continued harassment of Christians. War broke out, and Constantine again showed his military prowess. By 324 he became sole emperor of the whole Roman Empire.

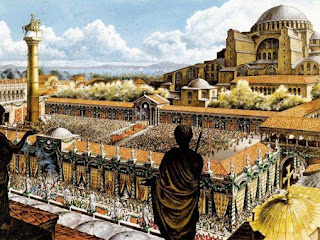

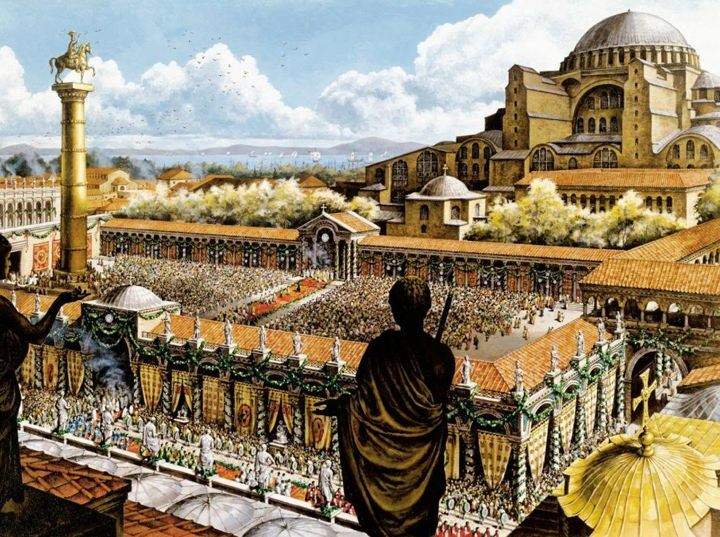

At once Constantine began to make arrangements to set up his capital in a safer part of the empire, in Byzantium (in modern-day Turkey) on the European side of the Bosporus. It was called New Rome, lower in rank than Italian Rome, but destined by Constantine to be upgraded over time.

When he made the city his home and named it after himself,

Constantinople

, it was the sign that the safety and prestige once the possession of the Latin world had permanently migrated eastward. The light of the Roman civilization moved east, and the West began its descent into darker times.

Constantine restored many of Diocletian’s reforms and renounced others. For example, he not only recognized the need for regionalized government; he set up armies to fight in the various European and Asian theaters of war. Germans and Franks entered into the higher ranks of imperial military service.

These concepts paved the way for medieval society, with local lords who controlled smaller territories and personal armies. Yet, he did not accept Diocletian’s idea of the college of emperors, or

Tetrarchy, and replaced it with a dynastic emperorship.

He separated the military from the civil in terms of services and duties. He set up a new currency and standardized its units, a system that lasted for 700 years. He held serfs and peasants to their social positions so that food production and imperial projects such as army campaigns, road maintenance, and city building could continue with ample supplies of food and labor.

At the same time he made a conscious effort to bring Christian values into public policies so that the downtrodden would be helped and especially the clergy could be promoted to a higher public status.

The results for the Christian Church were that bishops were welcomed into his courts, Christianity spread even more rapidly, and churches were reconstructed and given proprietary rights. He took an active interest in such church-building projects as St. Peter’s in Rome and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

At the same time, since Constantine saw himself as the mediator between God and his empire, he often took on the role of referee in church controversies, a role for which he was not educated. He summoned the

Council of Nicaea (325) and proposed the formula to be accepted to bring unity to all the Christians in his realm. Effectively speaking, Christianity achieved a prestige in the empire that future emperors such as

Julian the Apostate could not reverse.

Benefactor of The ChurchThe last few years of Constantine’s life were spent in the East, either in his capital or on campaign, although he occasionally traveled to Rome or the Rhine to secure his domain there. His military activities were confined to controlling the “barbarian” tribes along the frontier and not fighting Rome’s nemesis, the

Sassanid Empire. Later emperors were not so fortunate. Though a civil war broke out after his death, his influence was enough to give imperial prerogatives to his descendants for the next century.

Later Christians lionized such a benefactor of the church. It did not hurt that Constantine was buried next to the Church of the Apostles and de facto numbered among them as the “13th apostle.” His friend, Eusebius, revered by later generations of Christians as the historian of the early church, also added luster to the image of Constantine through his biography of the man. Other intervening and contemporary sources and evaluations of Constantine were less enthusiastic.

Around the ninth or 10th century, however, the reputation of Constantine soared to new heights as stories and legends abounded concerning his sanctity and supernatural acts. About 25 “lives” of Constantine have been recovered, both from the East and the West, which sing his praises beyond what was celebrated by earlier generations. As a saint in the Eastern Christian Church, his feast day is May 21.