The kingdoms of ancient Choson developed in Korea from the Bronze Age when tribal groups started to dominate the land between the Liao River in southern Manchuria, and the Taedong River in northern Korea. The legendary founder of the dynasty was Tan’gun, hailed by Koreans in modern-day North Korea and South Korea as the founder of their nations.

Tan’gun is claimed as an ancestor for the kingdom of ancient Choson; the term ancient is used to differentiate it from the

Yi dynasty, which ruled 1398–1910 c.e. and used the name Choson for Korea.

Ancient Choson from the fourth century b.c.e. was a series of tribal leagues that controlled the area from southern Manchuria to the Taedong River. It was powerful for more than 100 years at a time when China was preoccupied with what has become known as the Warring States period.

A major innovation in ancient Choson that enabled the kings to maintain their independence was the use of iron. Prior to this most warriors in the region had used bronze. It is believed that the northern Chinese may have introduced iron when they were escaping the attacks of the

Xiongnu (Hsiung-nu) or Huns.

One of these refugees was a former Chinese general called Wei Man (Wiman)who had served in the Chinese state of Yan (Yen). Wei Man was the descendant of important landowners in China during the

Zhou (Chou) dynasty and had been welcomed in Choson, as he and his followers were experienced soldiers.

They were given land in the north of Choson where they offered to act as frontier guards. Wei Man was given a jade insignia denoting his importance as a Korean general. As more Chinese refugees came to live on his lands, his number of potential supporters increased, and his power grew.

Very soon Wei Man realized that the kingdom was weak, and he had many supporters among the Chinese refugees who had already arrived in Choson and were either living in his lands or elsewhere in the kingdom. He also managed to get support from some local tribes who felt that they had not been well treated by the kings of Choson. In 190 b.c.e.

Wei Man wrote to the rulers of Choson saying that the Chinese had invaded from several sides, and he had to guard the king. He and his supporters then moved quickly on the Choson capital of Pyongyang on the pretext of protecting the royal court against a Chinese invasion, which everybody had feared for several hundred years.

Wei Man then took over the capital and the existing king, Chun, and went further south, establishing himself as King Han, which has no connection to the dynasty in China of the same name.

Wei Man, who claimed descent from the Chinese sage Qizi (Chi Tzu), used his contacts in China to ensure that the Chinese recognized him as a king, and he reciprocated by acknowledging the emperors of China. He established cordial relations with the governor of Liaodong (Liao-tung), the neighboring Chinese province.

However, the tribute that Wei Man had promised to the Chinese emperor was never sent. Wei Man and his descendants had initially felt that they were well entrenched, but when the civil war ended in China and the Han dynasty came to power, they faced several Chinese invasions.

Diplomatic problems first arose when some Chinese rebels who had been involved in the Seven Princes’ Rising in 154 b.c.e. fled to Korea. The Chinese were also sending out emissaries to some of the tribes who lived in northern Choson.

The actual dispute leading to the invasion was over tribute. A Chinese delegate visited Yu Ku (or Ugo), the grandson of Wei Man, to ask why no tribute had been paid. Furthermore, Yu Ku had tried to stop tribes that he felt were part of his kingdom from acknowledging their overlordship by the Han.

This was particularly true of the tribes on lands in central and southern Korea. Yu Ku realized the situation was tricky, but having built up a relatively strong army, he prevaricated and eventually the envoy returned to China.

On the return trip the envoy allowed his charioteer to kill a Korean prince who had been sent to escort him to the border. This envoy claimed that he had killed a Korean general and was applauded by the Chinese court that decorated him with the title “Protector of the Eastern Tribes of Liao Tung.”

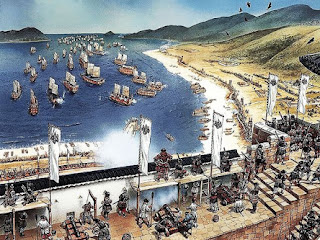

The Koreans protested, but a Chinese attack was inevitable and came in 109 b.c.e. when Emperor Wu of China sent his soldiers into Choson. Some 50,000 Chinese soldiers were dispatched by ship from Shandong (Shantung), with additional troops attacking by land.

The two armies were able to invade Korea, but their attacks were not coordinated, and they were unable to unite. As a result they were not able to defeat the Koreans in battle—the Koreans remained in their fortifications.

With the bitter winter imminent, the Chinese sent an envoy to Yu Ku who replied that he would accept the emperor of China as his overlord but would not send his son as a messenger in case he suffered the fate of the prince killed by the previous envoy. The only initial casualty of these negotiations was the Chinese envoy who was executed when he returned empty-handed.

In 189 b.c.e. the Chinese attacked the Koreans again, and this time they succeeded in seizing the kingdom and established four Chinese commanderies called Nangnang (Lolang in Chinese, Rakuro in Japanese), Chinbon, Imdun, and Hyont’o.

The latter three soon lapsed into Korean areas, with the Chinese only holding on to Nangnang. There a

Confucian school was established, and several historical texts were written that described some of the early events in Korean history. The Confucian Classics remain an important part of Korean culture.

Over the next 400 years the Koguryo tribes of northern Korea started agitating against Chinese rule. As they rose in power, they amassed a large army and in 313 c.e. ejected the Chinese from Nangnang. In 342 c.e. the Koguryo king, Kogugwon, established his capital at Hwando just north of the Yalu River.

Facing threats from China, it was soon moved to Pyongyang. There the Koguryo kingdom imported many ideas from China including

Buddhism, which is seen in many of the archaeological remains discovered in recent years.