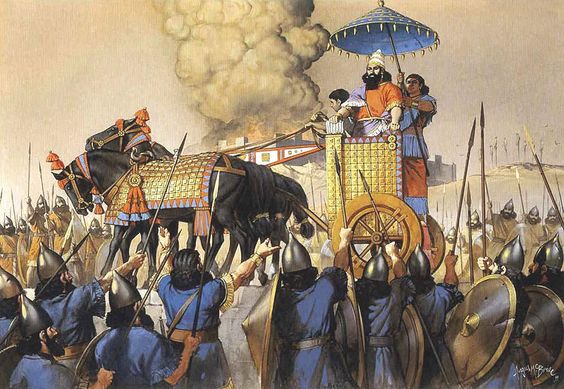

|

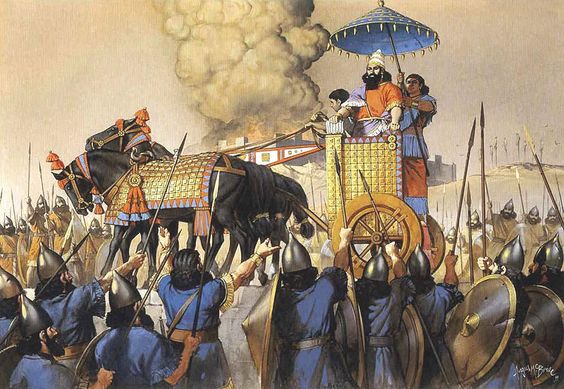

| Soldiers of Assyria Going to Battle |

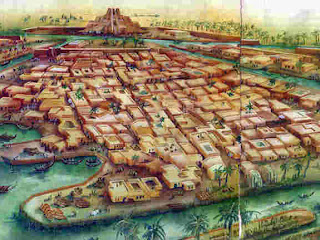

The country of Assyria encompasses the north of

Mesopotamia, made up of city-states that were politically unified after the middle of the second millennium b.c.e. Assyria derived its name from the city-state Ashur (Assur). This city was subject to the Agade king, Manishtushu, and the Ur III king, Amar-Sin.

During the Ur III period, Ashur also appears as the name of the city’s patron deity. Scholars have suggested that the god derived his name from the city and, indeed, may even represent the religious idealization of the city’s

political power.

The Old Assyrian PeriodThe Old Assyrian period (c. 2000–1750 b.c.e.) began when the city of Ashur regained its independence. Its royal building inscriptions are the first attested writing in Old Assyrian, an Akkadian dialect distinct from the Old Babylonian then used in southern Mesopotamia. This period also saw the institution of the limmu, whereby each year became named after an Assyrian official, selected by the casting of lots.

The sequence of limmu names is not continuous for the second millennium b.c.e., but has been completely preserved for the first millennium b.c.e. A solar eclipse (dated astronomically to 763 b.c.e.) has been dated by limmu and thus provides a fixed chronology for Assyrian and—by means of synchronisms—much of

ancient Near Eastern history.

During the Old Assyrian period Ashur engaged extensively in long-distance trade, establishing merchant colonies at Kanesh and other Anatolian cities. Ashur imported tin from Iran and textiles from Babylonia and, in turn, exported them to Kanesh. Due to political upheavals, Kanesh was eventually destroyed, and Assyria’s Anatolian trade was disrupted. Before this disaster, moreover, Ashur itself had been incorporated into the growing empire of Eshnunna.

Around the end of the 19th century b.c.e., the Amorite Shamshi-Adad I attacked the Eshnunna empire and conquered the cities of Ekallatum, Ashur, and Shekhna (renamed Shubat-Enlil). With the defeat of

Mari in 1796 b.c.e., Shamshi-Adad could rightfully boast that he “united the land between the Tigris and the Euphrates” in northern Mesopotamia. The Assyrian King List was manipulated so as to include Shamshi-Adad in the line of native rulers, despite his foreign origins.

In the new empire Shamshi-Adad reigned as “

Great King” in Shubat-Enlil, delegating his elder son, Ishme-Dagan, as “king of Ekallatum” and his younger son, Yasmah-Adad, as “king of Mari.” Government officials were frequently interchanged among the three courts.

|

| King of Assyria |

This mobility had the effect of homogenizing administrative practices throughout the kingdom, as well as creating loyalty to the central administration instead of to native territories. Shamshi-Adad’s empire, unfortunately, did not survive him for long. A native ruler, Zimri-Lim, reclaimed Mari and King Hammurabi of Babylon eventually subjugated northern cities such as Ashur and

Nineveh.

The four centuries after Ishme-Dagan are referred to as a “

dark age,” when historical records are scarce. During this time the kingdom of Mittani was founded. As it expanded its territory in northern Mesopotamia, the city-states once united under Shamshi-Adad became separate political units. The Middle Assyrian kingdom (1363–934 b.c.e.) began when Ashur-uballit I threw off the Mitannian yoke.

Whereas former rulers had identified themselves with the city of Ashur, Ashur-uballit was the first to claim the title “king of the land of Assyria,” implying that the region had been consolidated as a single territorial state under his reign. In his correspondence to

the pharaoh, Ashur-uballit claimed to be a “Great King,” on equal footing with the important rulers of Egypt, Babylonia, and Hatti.

Mitanni remained in the unenviable position of warfare on two fronts: the

Hittites from the north-west and Ashur-uballit’s successors from the east. Adad-nirari I annexed much of

Mitanni, extending Assyrian’s western frontier just short of Carchemish.

Shalmaneser I turned Mitannian territory into the Assyrian province of “Hanigalbat,” governed by an Assyrian official. His reign also witnessed the first seeds of Assyria’s policy on deportation: Conquered peoples were relocated away from their homeland in order to crush rebellious tendencies as well as to exploit new agricultural land for the empire.

Tukulti-Ninurta I conquered

Babylon and deposed the Kassite king, Kashtiliash IV. He appointed a series of puppet kings on Babylon’s throne, but a local rebellion soon returned control to the Kassites. This Assyrian monarch also set a precedent by founding a new capital, naming it after himself (“Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta”). Tukulti-Ninurta was eventually assassinated by one of his sons, and the rapid succession of the next three rulers suggests violent contention for the throne.

Stability returned to Assyria with the ascension of Ashur-resha-ishi I. Around this time the increased use of iron for armor and weapons greatly influenced the methods of Assyrian warfare. His son, Tiglathpileser I, achieved great victories in the Syrian region and even campaigned as far as the Mediterranean. He was the first to record his military campaigns in chronological order, thus giving rise to the new genre of “Assyrian annals.”

To the south conflict between Assyria and Babylonia was temporarily halted by the advent of a common enemy: the

Aramaeans. They were a nomadic Semitic people in northern Syria, who ravaged Mesopotamia in times of famine. Under this invasion Assyria lost its territory and may have been reduced to the districts of Ashur, Nineveh, Arbela, and Kilizi.

The Neo-Assyrian KingdomThe Neo-Assyrian kingdom (934–609 b.c.e.) began with Ashur-dan II, who resumed regular military campaigns abroad after more than a century of neglect. He and his successors focused their attacks on the Aramaeans to recover areas formerly occupied by the Middle Assyrian empire.

Adad-nirari II set the precedent for a “show of strength” campaign, an official procession displaying Assyria’s military power, which marched around the empire and collected tribute from the surrounding kingdoms. This monarch also installed an effective network of supply depots to provision the Assyrian army en route to distant campaigns.

Ashurnasirpal II has been considered the ideal Assyrian monarch, who personally led his army in a campaign every year of his reign. He subjected Nairu and Urartu to the north, controlled the regions of Bit-Zamani and Bit-Adini to the west, and campaigned all the way to the

Mediterranean.

Shalmaneser III continued his father’s tradition of military aggression. From his reign to Sennacherib’s (840–700 b.c.e.), the annual campaigns were so regular that they served as a secondary means of dating (i.e., the “Eponym Chronicle”). At Qarqar on the Orontes River in 853 b.c.e., Shalmaneser fought against a coalition led by Damascus, which included “[King] Ahab, the Israelite.”

Under Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III military strategy was honed to great effectiveness: When enemies refused to pay regular tribute, a few vulnerable cities would be taken and their inhabitants tortured by rape, mutilations, beheadings, flaying of skins, or impalement upon stakes.

This “ideology of terror” was designed to discourage armed insurrection, lest Assyria exhaust its resources. As a last resort, however, the foreign state would be annexed as an Assyrian province. The strategy of forced deportations was employed with reasonable success.

For the next century Assyria experienced a decline due to weakness in its central government, as well as the military dominance of its northern neighbor, Urartu. Tiglath-pileser III (biblical “Pul”), however, restored prestige to the monarchy by curtailing the power of local governors.

Instead of levying troops annually, he built up a standing professional army. Tiglath-pileser defeated the Urartians and invaded their land up to Lake Van. In the west an anti-Assyrian coalition was crushed, and the long recalcitrant Damascus was annexed. He also adopted a new policy toward Babylonia.

The Assyrian monarchs had traditionally restrained their efforts to control Babylonia, in deference to the latter’s antiquity as the ancestral origin of Assyria’s own culture and religion. In 729 b.c.e., however, Tiglath-pileser established a precedent by deposing the Babylonian king and uniting Assyria and Babylonia in a dual monarchy.

Hebrew tradition credits Shalmaneser V with the fall of Samaria in 722 b.c.e., the very last year of his reign. Two years later, however, Sargon II still had to crush a coalition led by Yaubidi of Hamath, who had fomented rebellion in Arpad, Damascus, and Samaria. The victory was depicted on relief sculptures in the newly founded royal city, Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad).

After a prolonged struggle, including a defeat by the Elamites at Der (720 b.c.e.), Sargon eventually wrested the Babylonian throne from Merodachbaladan II. In 705 b.c.e., however, Sargon’s body was lost in battle, prompting speculation about divine displeasure. Sargon’s successor, Sennacherib, eventually decided to move the capital to Nineveh.

During his 701 b.c.e. campaign in Palestine, Sennacherib became the first Assyrian monarch to attack Judah. He also attempted various methods of controlling Babylonia. When direct rule failed, Sennacherib installed a pro-Assyrian native as puppet king. There-after, he delegated the control of Babylonia to his son, who was later kidnapped by the Elamites. Finally, in 689 b.c.e. he razed Babylon to the ground.

Sennacherib was assassinated by two of his sons, a crime later avenged by another son, Esarhaddon. The latter was successful in his overtures to achieve reconciliation with Babylon. Esarhaddon may have overstretched Assyria’s limits, however, when he invaded Egypt and conquered Memphis in 671 b.c.e.

At his death Esarhaddon divided the empire between two sons: Ashurbanipal in Assyria and Shamashshuma-ukin in Babylonia. Egypt proved troublesome to hold, and Ashurbanipal eventually lost it to Psammetichus I. Moreover, civil war broke out between Assyria and Babylonia.

The Assyrians conquered Babylon by 648 b.c.e. and invaded Elam, which had been Babylon’s ally. Although successful, the civil war had taken its toll on Assyrian forces. Also, the crippled Elam was no longer a buffer between Assyria and the expanding state of Media.

In 614 b.c.e. the

Medes conquered the city of Ashur. Two years later, in coalition with the Babylonians and Scythians, they overthrew Nineveh. The defeated Assyrian forces fled to Haran, but the allied armies pursued them there and effectively ended the Neo-Assyrian kingdom in 609 b.c.e.