Tunisia entered the 19th century under the reign of Hammouda ibn Ali, the Bey of Tunis, as a minor Mediterranean power thanks to trade and extortion of European states through piracy (see the Barbary States), enjoying its quasi-independent autonomy from the Ottoman Porte in Constantinople. By the end of the 19th century, Tunisia fell in debt, the French achieved total economic control, the Bey signed a treaty with the French, stripping its sovereignty and placing the country under French protection whilst installing an appointed Resident-General from Paris to "advise" the Bey ( effectively a nominal ruler) and to oversee the country.

In this article, we shall delve into the details and events leading up to (and not after) the Treaty of Bardo, which solidified French control over the country.

|

| The Treaty of Bardo |

The French Maghreb:

Historically, Tunisia had ancient links with the European mainland. After all, the extinct Carthaginian civilisation originated here and along with it the Punic Wars with Rome. Just as those wars of ages past were about control over the Mediterranean, the story with Tunisia is remarkably familiar.

The French merchants of Marseille regularly traded goods to and from Tunisia, and it is no surprise the French made their first permanent presence in Tunis by establishing a consulate in 1577. During the height of the Age of Imperialism in the 18th century, the traditional influence of the French in Tunis was contested by the English, the Ottomans and the Italians. The French sought to assert their control through a series of concessional treaties, the most notable of which was signed in 1802 where the Bey formally acknowledged (to Napoleon) France's privileged position.

As France's economic power began to grew, the Bey's powers began to wane. His Turkish army corps had rebelled twice in 1811 and 1816, his naval forces suffered disastrously in 1827 after participating in the Battle of Navarino alongside the Ottomans (which he was obliged to do) during the Greek War of Independence. Outbreaks of plague in 1825 further weakened the Bey's economic capabilities. Weakened, the Bey had to sign a capitulation treaty in 1829 that allowed French citizens to only be tried by the French consul in Tunis.

| Tunisia (dark blue) with the rest of French Africa (light blue) |

French influence and power in the region grew greater after the 1830 invasion of Algeria. The French had numerous reasons to invade this autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire; raw materials, trading, establishment of settler colonies (but this is a topic for a different article). It is worth noting that the colonial policy to Algeria was greatly different than that of Tunisia. While Tunisia was to be a protectorate, Algeria was not to be a simple colony. It was a settler colony that officially became a part of France in 1848, where Republican workers and the unemployed from France would be shipped across the sea to their new homes, most of which were lands deprived from native Algerians.

The political fallout from the invasion of Algeria reached every capital throughout Europe. In Constantinople, the loss of Algiers was a blow to the already-declining Ottoman Empire. To the Germans, British and Italians, the French presence in Algeria presented a threat to their own imperial ambitions in the African continent and the Mediterranean and immediately began to seek ways to compensate (my previous post dealt with what the Italians did).

Within a month of the invasion, the Tunisians signed yet another treaty with the French, which opened the Tunisian market to French-manufactured goods, which undermined the country's traditional artisans and raised prices of local goods. The treaty also allowed European consuls to judge cases involving European citizens. As a result, European consuls were able to interfere in Tunisian domestic affairs.

Beys, Debts And A Constitution:

Ahmed Bey ruled Tunisia from 1837 to 1855 and it was under his rule that the beginning of the end had begun. When the benevolent Bey came to power, Tunisia's sovereignty was not only the target of French ambitions but of a newly-reinvigorated Ottoman Empire, eager to spread the Tanzimat (administrative restructuring and reform) that would strengthen the Sultan's control in the face of growing European powers. However, these reforms directly threatened the Bey's independence. The French, seeking to take advantage of the situation, offered to protect Tunisia from Ottoman and other European encroachment. Ahmed Bey declined, knowing what France's true intentions are.

|

| Ahmed Bey |

Mohammed Bey, Ahmed's successor, was more terrible. He overturned the abolition of slavery and administered his own arbitrary system of justice that was unfavourable to non-Tunisians, to the anger and frustration of European consuls. Concerned about the security and investment of their citizens, the British and French consuls pressured Mohammed Bey to accept reforms that provided greater security for foreigners. Adopted in September 1857, the Security Pact established legal equality between Tunisians and non-Tunisians, and gave Europeans the right to acquire property. These new freedoms, especially the new right to acquire property, made it easier for European interests to acquire a greater hold of the Tunisian economy.

This sparked calls by Tunisian intellectuals for the establishment of 'dustur' (دستور) or constitution which sought to create an institutionalised check on the Bey's power. Written in 1860, this was the Arab World's first constitution. In it, it confirmed the Bey as the hereditary head of state, it called for the establishment of a 60-member Supreme Council with substantial power that controls taxation and expenditure, whilst also having the ability to dismiss ministers.

The constitution only lasted for 4 years. The French and other European consuls did not like how it complicated their relationships with the Bey nor were they fond of the idea that their nationals would be subject to Tunisian law, which they argued violated previous treaties signed in the past. A flaw with the Supreme Council was that its members were directly appointed by the Bey himself. As a result, it did not live up to the expectations of Tunisian intellectuals. In 1864, the constitution was suspended and poll taxes were doubled to help pay the country's mounting debt. In response, Berber tribes and towns in the country's interior revolted. In 1866, the Tunisian government appealed to the Rothschild Banking House for 115 million francs to pay off the country's foreign debt. They refused.

Debts! Damn Debts And Conspiracies:

| |

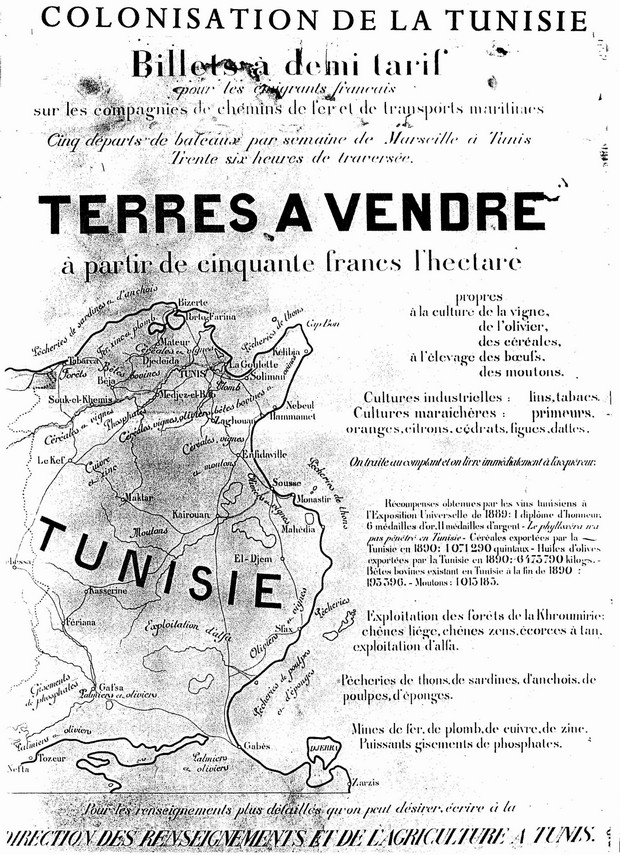

| Poster inviting French people to immigrate to Tunisia (1890) |

Tunisia's economic woes posed a conundrum to the European powers. On the one hand, France, Italy and Britain shared a common concern for their investments in the country (France particularly heavily invested in railroads, ports, mines and agriculture). Collapse of the Tunisian government and civil unrest was in none of their interests.

To avert the crisis, the International Financial Commission was established in 1869 to oversee Tunisia's budget. The Commission effectively controlled all state expenditure and organised the repayment of debts. On the other hand, the European powers distrusted each other; though France had the most economic presence in Tunisia, the Italians had the largest population residing there. The British primarily focused their attention on Egypt. Tunisia was seen by Paris as an important buffer between the East and Algeria, and its status needed to be determined decisively.

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Britain, France and Germany tried to reach an agreement. The German representative, the influential Otto von Bismarck suggested that France's interest in Tunisia should be recognised by both Germany and Britain. They pledged not to intervene in the event of a French claim or occupation of Tunisia. In return, Britain expected that the French would recognise Cyprus as British territory in the Eastern Mediterranean. Bismarck anticipated French resources and attention to be diverted to Africa, away from Europe. Once all this was agreed, they followed common diplomatic protocol and kept it a secret from the Ottomans, because this was basically the equivalent of carving up their empire.

|

| Congress of Berlin, 1878 |

By 1880, France controlled the railway and telegraph lines of Tunisia, established a low-interest bank to aid and encourage the growth of French agriculture and industry, invested in a new port in Tunis and in several mines in the countryside. With such heavy investments, it became impossible for the French not to be involved in domestic Tunisian economic and political issues. In the meantime, smuggling and drought made the International Financial Commission's job of paying government bonds harder. The French began to realise that protecting French investments would require more direct involvement.

In 1880, the French consul in Tunis, Adolphe-Francois de Botmilau commented:

"A last attempt is made in this moment to save this country by the financial commission. If it fails, we would have to be forcibly called upon to occupy Tunisia and this will be a troublesome extremity for us"

|

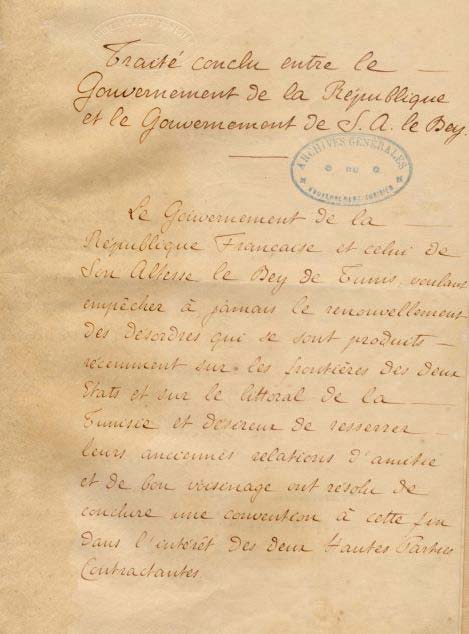

| Page 1 of the Treaty of Bardo |

But it was neither colonial nor economic hardship that eventually provoked a French occupation of Tunisia. According to the official narration, Khroumour tribesmen from Tunisia engaged in cross-border raids into French Algeria in March 1881. They were repelled by a joint Algerian-French force and felt that they had to cross into Tunisia.

Using this as an excuse, the French army of 36,000-strong occupied Bizerte, and soon turned south towards Tunis. Britain and Germany stood-by, as previously agreed in Berlin.. On 12 May 1881, the Bey signed the Treaty of Bardo, which gave France substantial control over Tunisia and placing the country under French protection where it remained until it achieved independence in 1956..

References:

- Christopher Alexander (2010). Tunisia: Stability and Reform in the Modern Maghreb. London: Routledge . p13-21.

- Assa Okoth (2006). A History of Africa: African societies and the establishment of colonial rule, 1800-1915. East African Publishers. p297-302

- Roslind Varghese Brown, Michael Spilling (2008). Tunisia. Marshall Cavendish. p21-36