|

| Nubia |

Egypt provides the earliest historical record of northern Sudan, the land of Kush at the First Cataract. The Egyptian name for Nubia was Kush, meaning "wretched". Kush encompassed modern-day northern Sudan and southern Egypt. Nubia was the place where African and Mediterranean civilizations met.

Nubia was sometimes under Egypt, sometimes independent, and has been inhabited for 60,000 years. By the eighth millennium b.c.e. Neolithic people lived a sedentary life in fortified mud-brick villages. They hunted, fished, gathered grain, and herded cattle.

They had contact with Egypt by means of the Nile. The Nubian city of Kerma produced ceramics as early as 8000 b.c.e., earlier than in Egypt. Nubia was rich in minerals and gold needed for building temples and tombs.

In the mid-fifth millennium b.c.e. central Sudan’s abundant savanna and lakes made a settled life with agriculture and domestication of animals possible for the Nubians who inhabited the region. The early Nubians engaged in a cattle cult similar to those found in Sudan and elsewhere in Africa today.

Around 2400 b.c.e. the Neolithic culture evolved into the Kerma culture, and Kush prospered due to trade in ebony, ivory, gold, incense, and animals to Egypt. By 1650 b.c.e. Kerma was a city-state with territory, stretching from the First Cataract to the Fourth. The power of Kerma rivaled that of Egypt.

Over time trade developed between Kush and Egypt, with Egyptian grain trading for

Kushite ivory, incense, hides, and carnelian. Periodic Egyptian military forays into Kush produced no permanent presence until the Middle Kingdom (2100–1720 b.c.e.). At that time the Egyptians built forts to protect shipments of gold mined at Wawat.

|

| Map of ancient Nubia |

From the Old Kingdom (2700–2180 b.c.e.) for 2,000 years Egypt dominated the central Nile region economically and politically. Even during times of diminished Egyptian power, the Egyptian religious and cultural influence remained strong in Kush.

The nomadic Asian Hyksos conquered Egypt around 1720 b.c.e., ending the Middle Kingdom, destroying the Nile forts, and cutting ties with Kush. An indigenous kingdom developed at Karmah. In 1500 b.c.e. Nubia fell to Egypt, which established an empire ranging from the Euphrates in Syria to the Fifth Cataract. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom ruled for more than 500 years.

Egyptian power renewed with the New Kingdom (c. 1570–1100 b.c.e.), and Kush became an Egyptian province that provided gold and slaves, with the children of local chiefs taken as pages in the Egyptian court to ensure the chiefs’ loyalty. As a province of Egypt, Kush became attractive to Egyptian settlers, including merchants, military personnel, government officials, and priests.

The Kushite elite converted to the Egyptian language, culture, and religion, preserving Egyptian culture and religion even during Egyptian decline and with temples to the Egyptian gods remaining in use until the coming of Christianity.

|

| Life in Nubia |

Egypt was weak and divided in the 11th century b.c.e., and Kush became autonomous for the next 300 years. Little is known about that period, but Kush reappeared as an independent kingdom in the eighth century b.c.e.

The Kushites conquered Upper Egypt in 750 b.c.e. and all of Egypt later in the century, ruling Kush and

Thebes for about 100 years. Egypt occupied Nubia for about 500 years. Then in 856 b.c.e. Nubia under the Twenty-fifth Dynasty ruled Egypt.

The dynasty at Napata was known as the Ethiopian dynasty, making it a great African power despite its holding to Egyptian culture and religion. Conflict with Assyria in the seventh century b.c.e. led to the withdrawal of the Kushite rulers from Egypt to their capital of Napata. In 713 b.c.e.

King Shabaka of Kush came to power. He controlled the

Nile Valley to the Delta. His dynasty fell to Assyria. In 590 b.c.e. an Egyptian incursion led to the relocation of the capital to

Meroë, and Egypt came under Persian, Greek, and Roman domination during subsequent centuries.

Isolated from Egypt, Kush developed its own culture, peaking in the third and second centuries b.c.e. The proximity to black Africa showed in the increased influence in Kushite civilization.

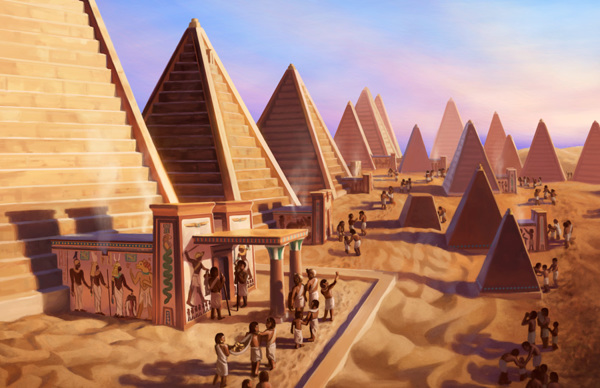

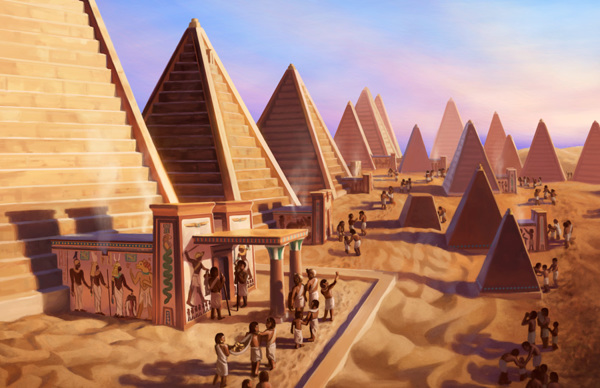

They modeled their jewelry on African styles. Meroë had an elected kingship with the succession strongly influenced by the queen mother. The rulers at Meroë continued the Egyptian practices of raising stelas as records of their exploits and using pyramids as their tombs.

The kingdom at Meroë enjoyed a centralized political system capable of bringing together the large numbers of artisans and laborers needed for building projects. The still-undeciphered Meroitic script that replaced Egyptian hieroglyphics in the first century b.c.e. was an adaptation of the Egyptian writing system.

Meroë prospered due to trade and commerce, especially after the introduction of the camel to Africa in the second century b.c.e. and the concurrent flourishing of the African caravan trade. Meroë benefited from its access to the Red Sea. It was noted for its pottery, woven cloth, and jewelry.

|

| Nubian royal family |

The kingdom also used Nile water and acacia trees (charcoal) to smelt iron for spears, arrows, axes, and hoes. It developed agriculture and

irrigation in a tropical region. In religion Kush worshipped the Egyptian state gods but also its own regional gods, including Apedernek, the lion god.

Over time northern Kush, home of the religious center of Napata, fell to predatory nomads, the Blemmyes. Nevertheless, Meroë maintained contact with the Mediterranean world through the Nile, dealt with Arab and Indian traders on the Red Sea coast, and began to include Hindu and Hellenistic cultural influences. Meroë had occasional friction with Egypt.

In 23 b.c.e. Meroë raided Upper Egypt, leading to Roman retaliation, the razing of Napata. The Romans regarded the area as too poor for colonization, so the army left. Meroë began to decline in the first or second century c.e. due to war with

Roman Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.

The manufacture of iron had exhausted the acacia forests, and deforestation caused the loss of fertility in the land. The Nobatae were horse- and camel-riding warriors who occupied the west bank of the Nile in northern Kush in the second century c.e.

Initially they sold protection to the Meroitic population. Then they intermarried and became the military aristocracy. Until around the fifth century, they received subsidies from Roman Egypt, which used Meroë as a barrier between itself and the Blemmyes.

During this period Meroë shrank as the Abyssinian state of Axum took over. In 350 Ezana, king of Axum, invaded Meroë. By then the Meroites had already given way to the Noba.

In the sixth century Meroë was home to three successor states: Nobatia, or Ballanah, in the north, with a capital at Faras in modern Egypt; Muqurra in the center, with a capital at Dunqulah; and Alwa in the south, with its capital at Sawba.

Warrior aristocrats ruled all three cities, but the court officials styled themselves after the Byzantine model. The Nubian kingdoms converted to Christianity in the sixth century.

The form of Christianity taken by the Nubian rulers was Monophysite Christianity, the Coptic version, and the spiritual head of the Nubian church was the Coptic patriarch of Alexandria, who held strong influence over the church and confirmed each ruler’s legitimacy. The monarch in return protected the church’s interests.

The queen mother preserved the Meroitic right to determine the succession, making possible the accession of nonroyal warriors through marriage. With the change to Christianity, Nubia reestablished cultural and religious ties to Egypt and renewed contacts with Mediterranean civilization.

The Nubian language replaced the Greek liturgy, but Coptic remained common in both religious and secular activities. Arabic grew in infl uence from the seventh century particularly in the world of commerce.

The Christian Nubian kingdoms attained their highest prosperity and military power in the ninth and tenth centuries. Arab domination of Egypt hampered Nubian access to the Coptic patriarch and ended the supply of Egyptian-trained clergy, causing the Nubian Christians to become isolated from the rest of Christianity.

Islam changed Sudan and split the south from the north. It also promoted political, economic, and educational development among its adherents, mostly in the urban commercial centers. Islam began spreading shortly after the death of Muhammad in 632.

Islam had converted the Arab tribes and cities, and Arab armies began spreading Islam into North Africa during the first generation after Muhammad’s death. Within 75 years North Africa was Muslim.

The conquest of Nubia began with invasions in 642 and again in 652, at which time the Arabs besieged Dunqulah (Dongala) and destroyed its cathedral. The Nubians refused to surrender, so the Arabs accepted an armistice and withdrew.

Nubians and Arabs had contacts long before the rise of Islam, and the process of Arabization took about 1,000 years. Intermarriage and exchange of cultural values were common.

With the failure of the early efforts at military conquest, the Arab commander in Egypt, Abd Allah ibn Saad, established the first of a series of treaties that lasted for almost 600 years. Arab rule of Egypt meant peace with Nubia. Periodically, non-Arabs ruled Egypt, and that generated conflict.

The Arabs wanted commerce and peace, and treaties facilitated travel and trade between the two. Trade flourished, with Arabs exchanging horses and manufactured goods for ivory, gum arabic, gems, gold, and cattle.

Arabs had treaty rights to buy Nubian land, and Arabs moved into Nubia as merchants, engineers in the gold and emerald mines, and pilgrims who used Nubian Red Sea ports, which also served as entrepôts for cargoes from India to Egypt.

Arab tribes who immigrated to Nubia during this time provide the ancestors of most of the region’s mixed population. The two most important are the Jaali and the Juhayna. The Jaali were sedentary farmers, herders, or townspeople.

The Juhayna families are nomadic descendants of 13th-century migrants into the savanna and semidesert regions. The Arabs and indigenous peoples intermarried. Arabization occurred without forced conversion or prosyletization.

The Christian kingdoms remained politically independent until the 13th century. Nubian armies invaded Egypt in the eighth and 10th centuries to free the imprisoned Coptic patriarch and reduce persecution of Copts under Muslim rule.

Then in the mid-14th century the kingdom of Makuria fell in a combination of conquest and intermarriage to the joint forces of the Juhayna Arabs and Mamluk. In 1276 the Mamluk (Arabic for "owned") soldier-administrator elites overthrew the monarch of Dunqulah and gave the crown to a rival.

Dunqulah was Egypt’s province. Nubia converted to Islam and Arabic. Intermarriage brought Arabs into the royal succession as the two elites merged. The king in 1315 was a Muslim prince of the royal Nubian line.

Islam expanded, and Christianity declined. In the 15th century Nubia became politically fragmented, and slave raiding became a major problem. Towns fearful for their safety asked for Arabic protectors. By the 15th or 16th century Arabs formed the majority in the region.