The Talon zipper factory in the city of Erie was located in the 900 block of West 26th Street, between Plum and Cascade streets. The factory was at its height of production during World War II manufacturing zippers for flight suits worn by the pilots who served during the war. The factory in Erie was a branch of the main factory that was located in the city of Meadville, in Crawford county. After the war, as business declined, the factory was closed in 1960, following the closing of the main factory in Meadville.

Though Talon survived, as a result of a merger with foreign interests, the business no longer exists in Erie or Crawford county.

Talon Zipper was company founded in 1893, originally as the Universal Fastener Company in Chicago, Illinois. Later, they moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, before finally settling in Meadville, Pennsylvania. It was in Meadville that the zipper as we know it was invented, until then they were producing hookless fasteners for boots and shoes. Meadville is where the zipper was mass-produced beginning in the 1920s. The high demand for zippers created favorable conditions for the Talon Company; thus, became Meadville’s most crucial industry.

The issue of where, how, and when the zipper was first invented has been steeped in controversy. Whitcomb Judson was the first to come up with the idea of a metal zipper in 1893, which he referred to as a clasp locker. Judson’s clasp locker consisted of a complicated hook-and-eye fastener that was used to open shoes. Judson designed this device for the Automatic Hook and Eye Company, but his design could not be mass produced easily and had the unfortunate habit of popping open unexpectedly. Swedish inventor Gideon Sundback created a design that used a slider and two rows of metal teeth. Sundback’s creation was more durable than Judson’s, and was much cheaper to produce. Because of these improvements, Gideon Sundback holds the patent for the zip fastener. As the patent holder, Sundback is commonly acknowledged as the inventor of the zipper. In 1906 Lewis Walker, who was excited about Sundback’s new design, took over control of the Automatic Hook and Eye Company, renaming it the Hookless Fastener Company.

Gideon Sundback was the first person to invent a relatively cheap, easy to produce zipper. Walker made the crucial decision to move manufacturing operations to Meadville, citing a wish to locate in a community where there is a minimum of labor troubles, where there are ample express facilities, and where the members of the concern and its employees may enjoy the comforts and advantages of pure air and water, good schools and wholesome influences. By November 1913 the newly named company was producing a thousand zip fasteners a day.

Although Hookless was capable of producing mass quantities of the fasteners they initially lacked the outlets to sell their product. In 1921 B.F. Goodrich Rubber designed galoshes that would use Sundback’s fasteners. The boots, which were originally going to be named the Mystik Boot, were renamed the Zipper when Goodrich employees reported that the company’s president showed boundless enthusiasm for the new design. The term zipper, initially the name of just the boot, eventually came to signify Sundback’s invention as well. Even though the boots were popular and helped Hookless turn a profit they were the only major product affiliated with the fastener company.

In 1937 some major changes took place. First, the Hookless Fastener Company changed its name to Talon, Inc. The name change was advantageous because it could be printed on the zipper tab itself, and it was easier for potential buyers to remember. In the same year, the zipper began to gain notoriety for its use on clothing. The Prince of Wales notably wore a suit with a zipper and more clothing designers began to incorporate zippers into their fashions. With new colors available, zippers became a must-have item on clothing of all types.

Fortunately, for the clothing industry, Talon was located in an ideal city to meet the demands of the newest fashion fad. In a decade when most other companies were firing workers and struggling to survive, Talon’s Meadville factories had to go to twenty-four hour production to meet demand. At the height of the zipper’s popularity the Meadville zipper factories employed 5,000 workers — out of a town with fewer than 19,000 people.

Talon had its best year ever in 1941, when demand for the zipper earned the company thirty-one million dollars in sales. Months later, wartime shortages dried up the supplies of copper alloy that the Meadville factories needed for their machines. For Meadville, the boom was over. Talon’s Meadville operations never recovered. Shortly after 1960 the struggling company was purchased by Textron, Inc., but then was re-sold in 1968. The Meadville managers, who tried to turn the company around, eventually were forced to sell the zipper company to the British textile company Coats Viyella PLC in 1991.

While Talon fruitlessly attempted to revive its pre-war boom Japanese manufacturer YKK capitalized on a worldwide demand for zippers. YKK opened a plant in New Zealand in 1959, followed in successive years by plants in the U.S., Malaysia, Thailand, Costa Rica and other textile-producing countries, taking full advantage of the cheaper labor offered by many of these nations. By constructing plants closer to areas of consumption, YKK provided itself with a more responsive distribution network guaranteeing timelier product delivery. By 1991 YKK had an international presence in forty-two countries with a mere thirty-percent of its 1.25 million miles of zippers being produced for domestic consumers. YKK surpassed Talon for the American market sometime in the 1980s, forcing Talon at the time to forgo the zipper business.

Talon’s rise and fall mirrored that of Meadville as well. The loss of manufacturing during the late 1970s and early 1980s created an unemployment rate just under twenty percent. The loss of Talon for good in 1993 left deep economic wounds. Today, nothing remains of Talon in Meadville. However, as a result of the need in manufacturing for the close tolerances, extant in tool and die making, a cottage industry of tool and die shops was established, which resulted in Meadville being nicknamed Tool City, with more tool shops per capita than any place else in the United States.

Though Talon survived, as a result of a merger with foreign interests, the business no longer exists in Erie or Crawford county.

Talon Zipper was company founded in 1893, originally as the Universal Fastener Company in Chicago, Illinois. Later, they moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, before finally settling in Meadville, Pennsylvania. It was in Meadville that the zipper as we know it was invented, until then they were producing hookless fasteners for boots and shoes. Meadville is where the zipper was mass-produced beginning in the 1920s. The high demand for zippers created favorable conditions for the Talon Company; thus, became Meadville’s most crucial industry.

The issue of where, how, and when the zipper was first invented has been steeped in controversy. Whitcomb Judson was the first to come up with the idea of a metal zipper in 1893, which he referred to as a clasp locker. Judson’s clasp locker consisted of a complicated hook-and-eye fastener that was used to open shoes. Judson designed this device for the Automatic Hook and Eye Company, but his design could not be mass produced easily and had the unfortunate habit of popping open unexpectedly. Swedish inventor Gideon Sundback created a design that used a slider and two rows of metal teeth. Sundback’s creation was more durable than Judson’s, and was much cheaper to produce. Because of these improvements, Gideon Sundback holds the patent for the zip fastener. As the patent holder, Sundback is commonly acknowledged as the inventor of the zipper. In 1906 Lewis Walker, who was excited about Sundback’s new design, took over control of the Automatic Hook and Eye Company, renaming it the Hookless Fastener Company.

Gideon Sundback was the first person to invent a relatively cheap, easy to produce zipper. Walker made the crucial decision to move manufacturing operations to Meadville, citing a wish to locate in a community where there is a minimum of labor troubles, where there are ample express facilities, and where the members of the concern and its employees may enjoy the comforts and advantages of pure air and water, good schools and wholesome influences. By November 1913 the newly named company was producing a thousand zip fasteners a day.

Although Hookless was capable of producing mass quantities of the fasteners they initially lacked the outlets to sell their product. In 1921 B.F. Goodrich Rubber designed galoshes that would use Sundback’s fasteners. The boots, which were originally going to be named the Mystik Boot, were renamed the Zipper when Goodrich employees reported that the company’s president showed boundless enthusiasm for the new design. The term zipper, initially the name of just the boot, eventually came to signify Sundback’s invention as well. Even though the boots were popular and helped Hookless turn a profit they were the only major product affiliated with the fastener company.

In 1937 some major changes took place. First, the Hookless Fastener Company changed its name to Talon, Inc. The name change was advantageous because it could be printed on the zipper tab itself, and it was easier for potential buyers to remember. In the same year, the zipper began to gain notoriety for its use on clothing. The Prince of Wales notably wore a suit with a zipper and more clothing designers began to incorporate zippers into their fashions. With new colors available, zippers became a must-have item on clothing of all types.

Fortunately, for the clothing industry, Talon was located in an ideal city to meet the demands of the newest fashion fad. In a decade when most other companies were firing workers and struggling to survive, Talon’s Meadville factories had to go to twenty-four hour production to meet demand. At the height of the zipper’s popularity the Meadville zipper factories employed 5,000 workers — out of a town with fewer than 19,000 people.

Talon had its best year ever in 1941, when demand for the zipper earned the company thirty-one million dollars in sales. Months later, wartime shortages dried up the supplies of copper alloy that the Meadville factories needed for their machines. For Meadville, the boom was over. Talon’s Meadville operations never recovered. Shortly after 1960 the struggling company was purchased by Textron, Inc., but then was re-sold in 1968. The Meadville managers, who tried to turn the company around, eventually were forced to sell the zipper company to the British textile company Coats Viyella PLC in 1991.

While Talon fruitlessly attempted to revive its pre-war boom Japanese manufacturer YKK capitalized on a worldwide demand for zippers. YKK opened a plant in New Zealand in 1959, followed in successive years by plants in the U.S., Malaysia, Thailand, Costa Rica and other textile-producing countries, taking full advantage of the cheaper labor offered by many of these nations. By constructing plants closer to areas of consumption, YKK provided itself with a more responsive distribution network guaranteeing timelier product delivery. By 1991 YKK had an international presence in forty-two countries with a mere thirty-percent of its 1.25 million miles of zippers being produced for domestic consumers. YKK surpassed Talon for the American market sometime in the 1980s, forcing Talon at the time to forgo the zipper business.

Talon’s rise and fall mirrored that of Meadville as well. The loss of manufacturing during the late 1970s and early 1980s created an unemployment rate just under twenty percent. The loss of Talon for good in 1993 left deep economic wounds. Today, nothing remains of Talon in Meadville. However, as a result of the need in manufacturing for the close tolerances, extant in tool and die making, a cottage industry of tool and die shops was established, which resulted in Meadville being nicknamed Tool City, with more tool shops per capita than any place else in the United States.

|

| Gideon Sundback was the first person to invent a relatively cheap, easy to produce zipper. |

|

| Gideon Sundback’s patent drawings for the modern zipper. |

|

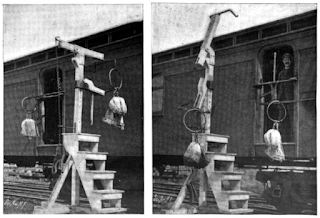

| Talon Zipper Factory in the City of Erie (year unknown) |