8 Kasım 2020 Pazar

5 Kasım 2020 Perşembe

Hirsch's "Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg" at WHS

The next meeting of the Washington History Seminar will be devoted to Francine Hirsch, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and her book, Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg: A New History of the International Military Tribunal After World War II. It will be held on Thursday, November 12 at 4:00 pm ET. Click here to register.

Organized in the wake of World War Two by the victorious Allies, the Nuremberg Trials were intended to hold the Nazis to account for their crimes and to restore a sense of justice to a world devastated by violence. As Francine Hirsch reveals in her groundbreaking new book, a major piece of the Nuremberg story has routinely been left out: the critical role of the Soviet Union. Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg offers a startlingly new view of the International Military Tribunal and a fresh perspective on the movement for international human rights that it helped launch.

--Dan Ernst

1 Kasım 2020 Pazar

Gerstle & Isaac, eds., "States of Exception in American History"

New from the University of Chicago Press: States of Exception in American History, edited by Gary Gerstle (University of Cambridge) and Joel Isaac (University of Chicago). A description from the Press:

States of Exception in American History brings to light the remarkable number of instances since the Founding in which the protections of the Constitution have been overridden, held in abeyance, or deliberately weakened for certain members of the polity. In the United States, derogations from the rule of law seem to have been a feature of—not a bug in—the constitutional system.

The first comprehensive account of the politics of exceptions and emergencies in the history of the United States, this book weaves together historical studies of moments and spaces of exception with conceptual analyses of emergency, the state of exception, sovereignty, and dictatorship. The Civil War, the Great Depression, and the Cold War figure prominently in the essays; so do Francis Lieber, Frederick Douglass, John Dewey, Clinton Rossiter, and others who explored whether it was possible for the United States to survive states of emergency without losing its democratic way. States of Exception combines political theory and the history of political thought with histories of race and political institutions. It is both inspired by and illuminating of the American experience with constitutional rule in the age of terror and Trump.

Some chapters that are especially likely to interest our readership:

4 The American Law of Overruling Necessity: The Exceptional Origins of State Police Power

5 To Save the Country: Reason and Necessity in Constitutional Emergencies

6 Powers of War in Times of Peace: Emergency Powers in the United States after the End of the Civil War

9 Constitutional Dictatorship in Twentieth-Century American Political Thought

10 Frederick Douglass and Constitutional Emergency: An Homage to the Political Creativity of Abolitionist Activism

14 Ekim 2020 Çarşamba

Losano on War Prohibitions in Postwar Constitutions of Japan, Italy and Germany

The Max Planck Institute for European Legal History announces a new publication, Three constitutions against war: Japan, Italy, Germany, by Mario G. Losano. It is Volume 14 of the Open Access series Global Perspectives on Legal History:

The three defeated powers from the Second World War incorporated provisions prohibiting wars of aggression into their post-war constitutions, which are still in force. The first part of the book covers the difficult years for Japan, Italy and Germany between the end of the war and the start of peace (with the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials, denazification, reparations and the renewal of the school system), analysing the birth of the three constitutions between 1947-49.

The consequences of defeat were different in each of the three countries, and hence each followed its own path in formulating the prohibition on war. However, the division of the world into two hostile blocs required the three countries to rearm, thus launching a process that resulted in the watering down of the original prohibition on war. In fact, the three countries’ involvement in international bodies requires each of them to participate in new wars, which are now branded as “peacekeeping” missions. There have thus been increasingly frequent calls to modify or even revoke these pacifist articles, above all in Japan (due to its geopolitical position).

The second part looks at three extensive annexes of documents that detail a specific aspect of each of the three states’ constitutional pathways. Japanese pacifism is examined with reference to the Allied documents that laid the groundwork for the post-war constitution. This leads to a consideration of current political debates concerning the amendment of the pacifist article, under pressure from Russian and Chinese interests coupled with the threat of North Korean aggression. With regard to Italy, its interest in Japan through the figure of the soldier-poet Gabriele D’Annunzio and his “samurai brother” is considered, alongside the now-forgotten “Partisans for Peace” movement, drawing on two unpublished documents. Germany, on the other hand, was divided into two countries after the World War II, with West Germany adopting a “Basic Law”, which has now been extended to the reunified Germany. The book considers excerpts from the reports of the constituent assembly concerning the adoption of the pacifist article. The equivalent East German legislation is documented in more summary terms, as that legal system is now little more than a historical footnote.

This threefold historical-constitutional inquiry provides an account of the birth and development of the pacifist article imposed by the victorious Allies, thus allowing for a better understanding of current debates concerning its impending modification.

--Dan Ernst

17 Ağustos 2020 Pazartesi

Benvenisti & Lustig, "Monopolizing War: Codifying the Laws of War to Reassert Governmental Authority, 1856–1874"

In this article, we challenge the canonical narrative about civil society’s efforts to discipline warfare during the mid-19th century – a narrative of progressive evolution of Enlightenment-inspired laws of war, later to be termed international humanitarian law. Conversely, our historical account shows how the debate over participation in international law-making and the content of the law reflected social and political tensions within and between European states. While the multifaceted influence of civil society was an important catalyst for the inter-governmental codification of the laws of war, the content of that codification did not simply reflect humanitarian sensibilities. Rather, as civil society posed a threat to the governmental monopoly over the regulation of war, the turn to inter-state codification of IHL also assisted governments in securing their authority as the sole regulators in the international terrain. We argue that, in codifying the laws of war, the main concern of key European governments was not to protect civilians from combatants’ fire, but rather to protect combatants from civilians eager to take up arms to defend their nation – even against their own governments’ wishes. We further argue that the concern with placing ‘a gun on the shoulder of every socialist’ extended far beyond the battlefield. Monarchs and emperors turned to international law to put the dreaded nationalist and revolutionary genies back in the bottle. These concerns were brought to the fore most forcefully in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 and the subsequent short-lived, but violent, rise of the Paris Commune. These events formed the backdrop to the Brussels Declaration of 1874, the first comprehensive text on the laws of war. This Declaration exposed civilians to war’s harms and supported the growing capitalist economy by ensuring that market interests would be protected from the scourge of war and the consequences of defeat.The full article is gated, unfortunately.

-- Karen Tani

3 Ekim 2019 Perşembe

History of War: Battle of Brunanburh

There are various accounts of this climactic battle. The most important and earliest is the heroic poem found in four different manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

According John of Worcester, Constantine, the Scottish king, was Olaf's father-in-law, so that alliance between the Scots and the Norse Vikings was cemented by marriage. Moreover, John, alone of all the chroniclers, records that the coalition fleet entered the Humber. He records the place of the battle as Brunanburh.

In 937 Northern alliance arrives to take on Æthelstan, led by Olaf Guthfrithson, Constantine and Owen, King of Strathclyde. They were defeated by Athelstan and his brother Edmund with great slaughter at Brunanburh in the year 937.

The Battle of Brunanburh forms one of the most important events in the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The preparations for the conflict exhausted the naval and military resources of the Danish colonists, and its issue consolidated the power and raised the Saxon name to the highest dignity among the states of Europe.

Of upwards of 100,000 combatants engaged on both sides, probably the greatest portion perished on the field or during the pursuit; for of the confederated forces led by Olaf Guthfrithson, only a shattered remnant survived to tell the tale of their defeat.

History of War: Battle of Brunanburh

24 Ağustos 2019 Cumartesi

American Civil War (1861-65)

It was a social and military conflict between the United States of America in the North and the Confederate States of American in the South.

Both sides had advantages and weaknesses. The North had a greater population, more factories, supplies and more money than the South. The South had more experienced military leadership, better trained armies, and the advantage of fighting on familiar territory.

Combat began on 12 April 1861 at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, and intensified as 4 more states joined the South. Although many Confederate and Unionist leaders believed the war would be short, it dragged on until 26 May 1865, when the last major Confederate army surrendered.

American Civil War (1861-65)

1 Haziran 2019 Cumartesi

The Battle of Didgori in 1121

With the adoption of Christianity as the official religion, Georgia found itself in a difficult position: the collapse of Byzantium turned the Christian country into the only outpost in a Muslim milieu. For that reason it was troubled endlessly by the Arab, Persian and Turk invaders.

On August 12, 1121, in the Didgori battle near Tbilisi, Georgian troops of 56 000 warriors defeated a 300,000 strong Moslem coalition army. Georgia repelled an invasion by Seljuk Sultan of Baghdad (subordinate to the Eastern Great Seljuks) at Didgori, and acquired Tbilisi.

In Georgian history it is known as dzleva sakvirveli the “wonderful history”. Five hundred citizens were tortured to death, and much of the city burned. Tbilisi became a royal town, the capital of Georgia and in time los its self-governing status.

The capture of Tbilisi by David IV the Builder in 1121 constituted one of the most significant events in Georgian history. The significance of the liberation of this major east-Georgian city from the five-century-long Muslim domination was not limited to the mere territorial expansion, but heralded quite unequivocally Georgia’s de-facto status of the major3 Christian nucleus of power in the Caucasus, at times providing “the second front” diversion for the Crusaders’ foes in Palestine and Syria.

David the Builder died in 1125, leaving Georgia as a great power. His successor Demetrius I (1125-1156) maintained it as such, but followed a status quo policy.

The Battle of Didgori in 1121

15 Aralık 2015 Salı

The Polish Exodus To Iran in World War 2

|

| A Polish woman decorates her tent, in an American Red Cross camp in Tehran, Iran. 1942 |

Time for some backstory. It's September 1939 - Germany and the Soviet Union have invaded Poland and partitioned the country between the two. To say life was miserable for the Polish at this time would be an understatement. The Soviet Union interned over 320,000 Polish citizens and deported them to Siberia for work in the infamous Gulags. Another 150,000 Poles died, in gruesome massacres such as the Katyn massacre. Stalin began emptying Poland of anyone who could resist the occupation. First went military officers and their families, then the intelligentsia, and last anyone with wealth, influence or education.

Fast forward to 1941 and Nazi Germany launched a full-scale invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa, the largest military campaign in history). Officially on the side of the Allied powers in July 1941, Joseph Stalin signed a Polish-Russian agreement that led to the foundation of a Soviet-backed Polish army that was to be made up of Polish prisoners of war who were 'pardoned' from the Gulags. The formation of such an army would take place in British-occupied Iran.

With news of their mass release, Poles began to slowly make their way towards Iran. With the Polish government in exile unable to assist their compatriots, and the Soviets refusing to allow access to trains to facilitate their exodus, fatalities due to hunger, the Siberian cold, violence, disease and simple exhaustion were high. By August 1942, a conservative estimate suggests more than 115,000 Poles (included 40,000 civilians) fled to Iran. At most, it is thought 300,000 Poles fled.

Camp Polonia:

The soldiers who enlisted in Anders' Army (named after its commander Władysław Anders) regrouped in Bandar Pahlavi, Mashhad and eventually Ahvaz, before being transferred to British command in Mandatory Palestine.

| |

| Young Polish refugee at a camp operated by the Red Cross in Tehran, Iran. Nick Parrino, 1943 |

The Iranian and British officials who first watched the Soviet oil tankers and coal ships list into the harbour at Pahlavi on the 25th March 1942 had little idea how many people to expect or what physical state they might be in. Only a few days earlier, they had been alarmed to hear that civilians, women and children, were to be included among the evacuees, something for which they were totally unprepared.[4] The ships from Krasnovodsk were grossly overcrowded. Every available space on board was filled with passengers. Some of them were little more than walking skeletons covered in rags and lice. Holding fiercely to their precious bundles of possessions, they disembarked in their thousands at Pahlavi and kissed the soil of Persia. Many reportedly sat down on the shoreline and prayed, or wept for joy.

They had not quite escaped, however. Weakened by two years of starvation, hard labour and disease, they were suffering from a variety of conditions including exhaustion, dysentery, malaria, typhus, skin infections, chicken blindness and itching scabs. The spread of typhus in particular was deadly to such an extent that 40% were hospitalised and a large proportion later died.

|

| Overcrowded ship crossing the Caspian Sea to Pahlavi |

Gholam Abdol-Rahimi, a struggling photographer in Pahlavi, emerged from bed to witness ships disgorging disheveled refugees. Abdol-Rahimi's photographs are perhaps the most complete account of the catastrophe. But his work was never recognized or published.

Pahlavi was only a temporary shelter. Refugees were later dispersed to more prepared camps in Isfahan (Isfahan in particular being dubbed as the 'City of Polish Children'), Tehran and Ahvaz.

More than 13,000 of the arrivals in Iran were children, many orphans whose parents had died on the way. In Russia, starving mothers had pushed their children onto passing trains to Iran in hopes of saving them.

As the war dragged on, most refugees continued their journey away from the Soviet Union, reaching Pakistan, Palestine and British East Africa & South Africa, eventually to the United Kingdom and the United States.

|

| The Polish cemetery in Bander Anzali (Pahlavi) |

|

| Polish military cemetery, Tehran. |

Forgotten Polish Exodus to Persia - Washington Post

The Exile Mission: The Polish Political Diaspora and Polish Americans, 1939-1956. Anna D. Jaroszyńska-Kirchmann. page 26-27

The Polish Deportees of World War II: Recollections of Removal to the Soviet Union and Dispersal Throughout the World. Tadeusz Piotrowski. page 10-12.

1 Eylül 2015 Salı

Does History Repeat Itself?

First of all, let's get the fine print out of the way; every moment in time itself is unique and forever lost. You never obtain the exact same conditions (unless you happen to own a rather expensive real life Sim game). So technically history cannot literally repeat itself, unless you're a fervent believe in radical physics theories.

And now to the actual discussion. Does history in fact repeat itself? There are common themes throughout the history of human civilisations. Let's take the example of religion. All cultures, from the huts of the Mongolian steppes to the rainforests of Central America have a religion of sorts; Animism, Shamanism, Christianity, Islam and so on. The absence of a so-called 'Atheist civilisation' may be a simple coincidence. It could be a by-product of human curiosity; What is the warm life-giving Sun? Why does the Sun set and so on... It has to be a superior being (which is probably why religions from Germanic paganism to Roman mythology feature it so prominently). But I'll leave you to ponder on that.

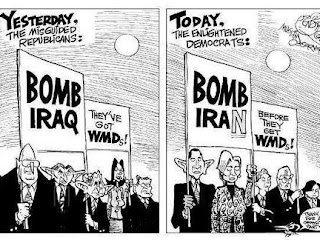

But I digress with all this philosophy. Time for actual history. You'd be forgiven if you looked at certain events in the past and thought "huh, this is familiar? Didn't this happen before?", especially as the current media scramble over the Iran deal in the US Congress. Advocating for the invasion of a country which is allegedly constructing a nuclear stockpile without sufficient evidence (and whose aftermath would trigger a power vacuum that would cause the region to spiral into a chaotic darkness of perpetuity) sounds incredibly familiar, you may be thinking.

History has a habit of striking similarities. Invasions of Russia in the winter (or ever) have never succeeded (see Napoleon's invasion in 1812 and Hitler's invasion in 1941) unless you discount the Mongols who wisely invaded from the other side. The same could be said to Afghanistan, earning the title of Graveyard of Empires due to the exceptional difficulty of pacifying the region throughout history (Alexander the Great, the Mughal Khans, the British, the Soviets and currently, the American coalition).

A nation under financial turmoil breeds the rise of radical xenophobic nationalists of the far right; the rise of Hitler & the Nazi Party in a 1930s depression-hit Germany is the most noted of examples. Not too long ago in 2012 did the Greek far right party Golden Dawn win 21 seats (its first ever representation in Greek parliament). The good news is that in subsequent elections, that figure is now down to 17 and with even more elections around the corner, we can be hopeful that number slides down.

Allow me to bring the 5th century Byzantine historian Zosimus into the framework. Zosimus highlighted that great empires fell due to internal conflicts and disunity. Citing the fallen empires of the Greeks and Alexander's Macedon, he brought attention to the need for an external enemy. The rapid growth of the Roman Republic in 53 years, he credited, was due to the devastating Punic Wars fought against Rome's bitter rival, Carthage. Roman themes were embraced and thus championed in the the face of Carthaginian foes. The defeat of Carthage (and the Gauls) set the scene for internal quarrels and civil war, culminating in the replacement of Roman aristocracy with monarchy, which eventually decayed into tyranny.

The eventual fall of all empires was a notion brought up earlier by Dionysius of Halicarnassus who had anticipated Rome's eventual collapse after the defeat of her rivals (Assyria, Macedonia, Persia). The iconic Italian historian Machiavelli commented on the recurrent themes between "order" and "disorder" within contemporary Italian states between 1434-1494:

..when states have arrived at their greatest perfection, they soon begin to decline. In the same manner, having been reduced by disorder and sunk to their utmost state of depression, unable to descend lower, they, of necessity, reascend, and thus from good they gradually decline to evil and from evil mount up to good.Machiavelli accounts for this oscillation by arguing that virtù (valor and political effectiveness) produces peace, peace brings idleness (ozio), idleness disorder, and disorder rovina (ruin). In turn, from rovina springs order, from order virtù, and from this, glory and good fortune.

This post can go on forever. To paraphrase Mark Twain; history does not repeat itself. Not exactly, anyways. But it does rhyme. I'll conclude by sharing one of my favourite cartoons on the topic. Let me know what you think in the comment section below!

13 Ağustos 2014 Çarşamba

Yang Kyoungjong - A Conscript's Story

| Yang Kyongjong (left) in Wehrmacht attire following capture by American paratroopers in June 1944 after D-Day |