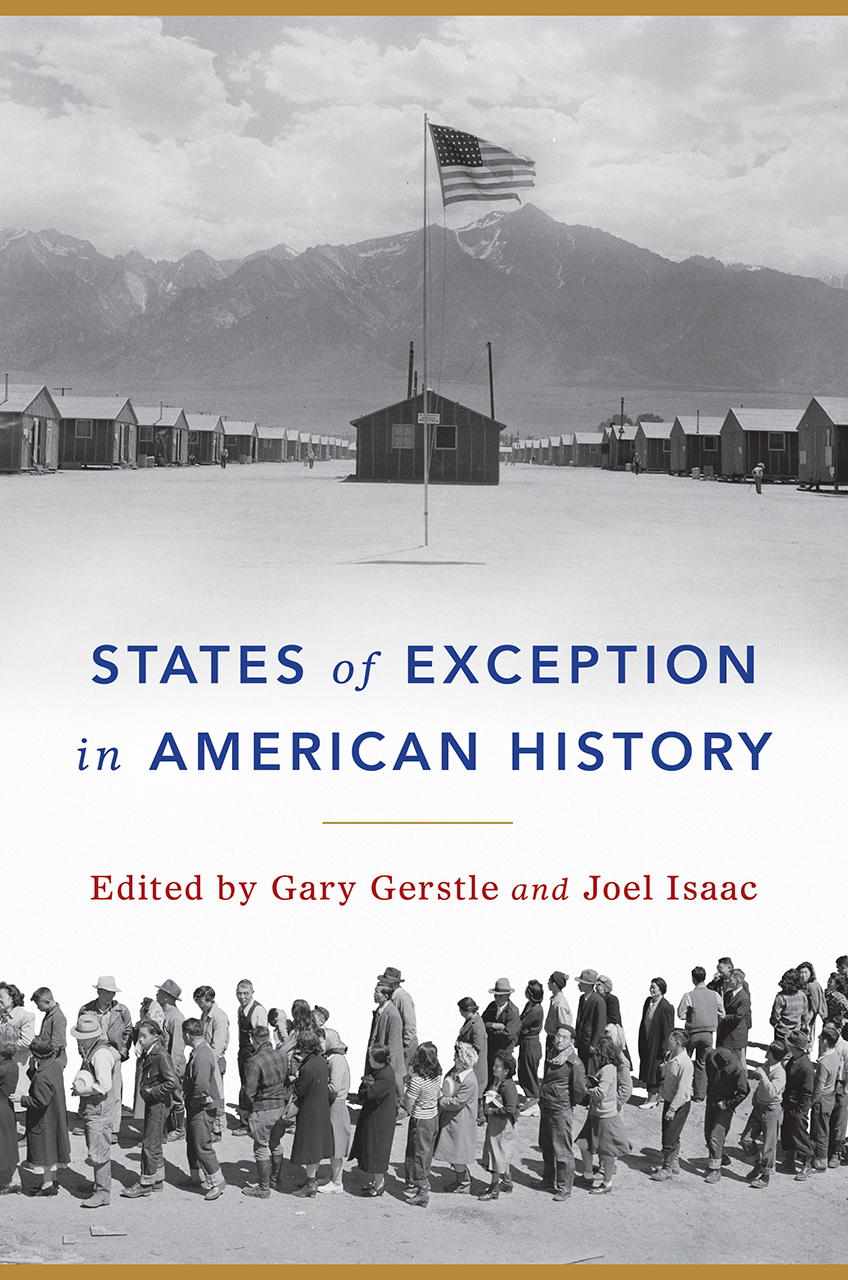

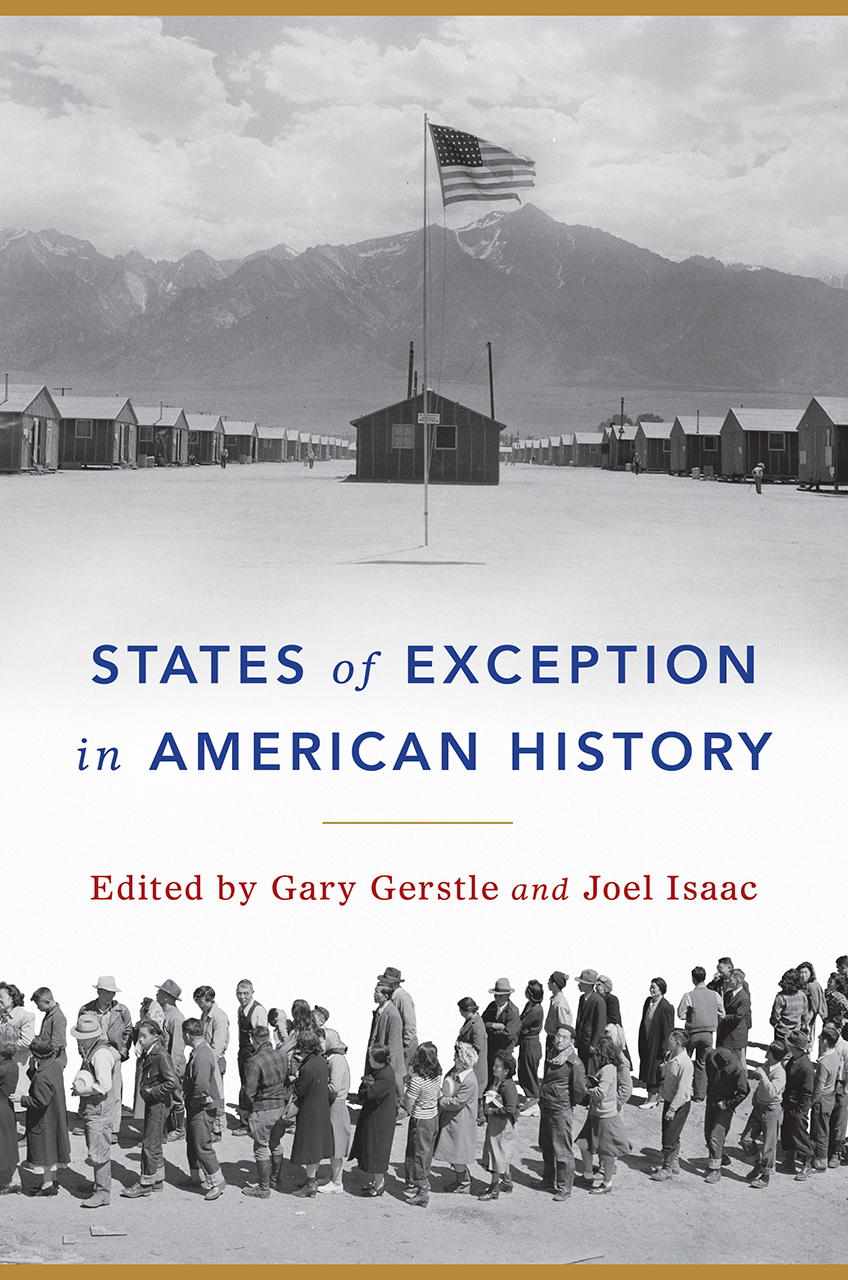

New from the University of Chicago Press: States of Exception in American History, edited by Gary Gerstle (University of Cambridge) and Joel Isaac (University of Chicago). A description from the Press:

States of Exception in American History brings to light the remarkable number of instances since the Founding in which the protections of the Constitution have been overridden, held in abeyance, or deliberately weakened for certain members of the polity. In the United States, derogations from the rule of law seem to have been a feature of—not a bug in—the constitutional system.

States of Exception in American History brings to light the remarkable number of instances since the Founding in which the protections of the Constitution have been overridden, held in abeyance, or deliberately weakened for certain members of the polity. In the United States, derogations from the rule of law seem to have been a feature of—not a bug in—the constitutional system.

The first comprehensive account of the politics of exceptions and emergencies in the history of the United States, this book weaves together historical studies of moments and spaces of exception with conceptual analyses of emergency, the state of exception, sovereignty, and dictatorship. The Civil War, the Great Depression, and the Cold War figure prominently in the essays; so do Francis Lieber, Frederick Douglass, John Dewey, Clinton Rossiter, and others who explored whether it was possible for the United States to survive states of emergency without losing its democratic way. States of Exception combines political theory and the history of political thought with histories of race and political institutions. It is both inspired by and illuminating of the American experience with constitutional rule in the age of terror and Trump.

Some chapters that are especially likely to interest our readership:

2 Negotiating the Rule of Law: Dilemmas of Security and Liberty Revisited

Ewa Atanassow and Ira Katznelson

4 The American Law of Overruling Necessity: The Exceptional Origins of State Police Power

William J. Novak

5 To Save the Country: Reason and Necessity in Constitutional Emergencies

John Fabian Witt

6 Powers of War in Times of Peace: Emergency Powers in the United States after the End of the Civil War

Gregory P. Downs

9 Constitutional Dictatorship in Twentieth-Century American Political Thought

Joel Isaac

10 Frederick Douglass and Constitutional Emergency: An Homage to the Political Creativity of Abolitionist Activism

Mariah Zeisberg

More information is available

here.

-- Karen Tani